THE JOURNAL

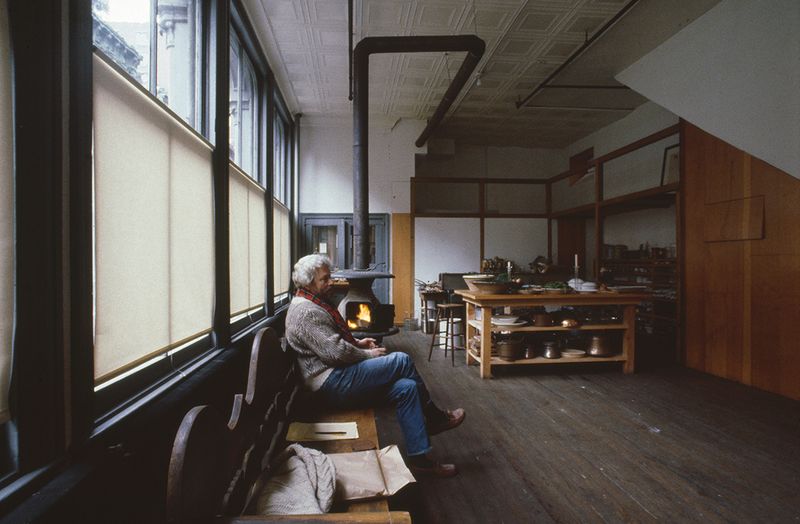

Mr Donald Judd, 2nd Floor, 101 Spring Street, New York, 1985. Photograph by Ms Doris Lehni-Quarella/Mr Antonio Monaci. Licensed by ARS

It’s a slightly tricky proposition writing about Mr Donald Judd (1928-1994), the artist whose bold, industrial and geometric sculptures and paintings made him a leading figure of the new, pared-back style of art that emerged from New York in the 1950s and 1960s. Tricky, and imposing, chiefly because he so virulently disliked the vast majority of what was being written at the time. He was critical of art critics and bristled at the generic terms – such as “minimalist” and “monumental” – that they invented to describe his (and others’) work. He mistrusted the way in which, during his lifetime, the art world continued to favour the academic over the visual, and he bemoaned the proliferation of what he called “literary” (that is, overly narrative conceptual art). At times, he seemed antagonistic to the very idea of analysing art at all, a case in point being his 1983 essay “Art And Architecture”, in which he argues, essentially, that art explains itself, its content and form being indivisible. What’s more, he tended to write off his own writing as damage control. Only by putting his own pen to paper, he claimed, could he make sure that his work wasn’t spoken about, incorrectly, by other people – “most of whom cannot think” (as he put it in the 1975 essay “Imperialism, Nationalism And Regionalism”).

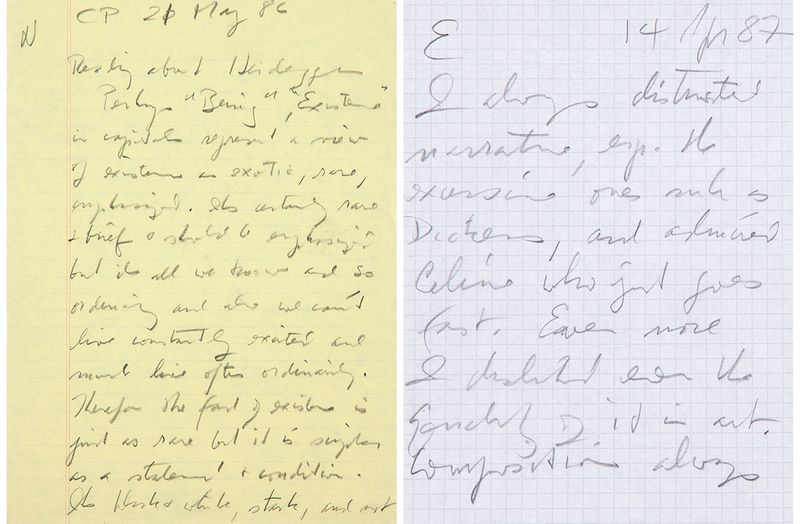

Despite all this, the temptation to write about Mr Judd remains strong, particularly in light of the publication this November of Donald Judd Writings, a new, comprehensive collection of his essays, criticism and notes, which follows the reissue of his Complete Writings 1959-75 in March this year. Poring through this volume – aptly described in its front matter by Mr Judd’s son Flavin as a “toolbox of ideas” – you can’t help but note that, though Mr Judd had many misgivings about writing, he was spectacularly good at it. His style, contrary to the dominant tone of art criticism, is to-the-point, polemical and bullishly charming, all of which qualities emerge especially strongly in his previously unpublished “Notes” from various eras – published for the first time in this edition. These take no prisoners, and are hugely entertaining. “I think too much is being asked of art to expect millions of people to be interested,” he writes, in a note from 1985. “It’s not sports, it’s not the Super Bowl. Great popularity is not going to happen.” Another, dated 13 June 1987, simply reads: “Philip Johnson’s Glass House is discreetly vulgar.”

Handwritten notes from 1986 and 1987. Photograph © Judd Foundation. Licensed by ARS

Mr Judd was, of course, an incisive thinker when it came to art – demonstrated by the many now-famous essays collected here, including 1964’s “Specific Objects” (a landmark text that proposed a new way of thinking about how painting and sculpture occupy space, as well as the suggestion of a new category of art somewhere in between the two) and 1982’s “On Installation” (in which the artist explains the importance of creating spaces where artists’ works could be properly, and permanently installed). For admirers of Mr Judd’s works, the Complete Writings also contains much thinking about how he produced them, from the 1981’s “Russian Art In Regard To Myself” to a series of later pieces describing how he built The Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas.

However, it turns out, Mr Judd was equally insightful when it came to other areas beyond art, from architecture to design, politics and society to philosophy. In fact, many of the things that concerned Mr Judd in the latter half of the 20th century are issues we are still grappling with today: the growth of globalised corporatism; the troubling spectre of nationalism; the debasement of culture for and by mass audiences; the soullessness of contemporary architecture. Overall therefore, these works represent not just a fascinating slice of art history and the 20th century, but a great thinker occupied with the daunting task of revealing cultural clichés for what they are and challenging assumptions as to why and how we create things – words, objects, wars, buildings, labels. “I’m still twenty years ahead of everyone twenty years after I was twenty years ahead,” said Mr Judd in 1987 to the artist Mr Dan Flavin (according to a note dated 4 May of that year). The overriding feeling is that, where Mr Judd is concerned, the same still holds true, and will do for many sets of 20 years to come, which makes this required reading for anyone with a creative mindset.

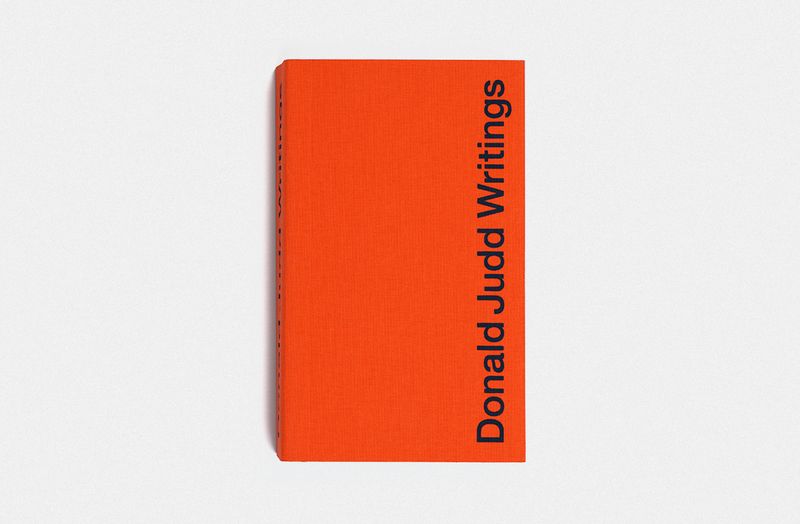

Photograph by Mr Sol Hashemi/Judd Foundation

Donald Judd Writings is published this November by the Judd Foundation and David Zwirner Books, and is accompanied by a programme of talks discussing Mr Judd’s writings in New York and Marfa.