THE JOURNAL

From left: Mr Riaz Phillips. Photograph by Ms Kindima Bah. Slow stew peas. Photograph courtesy of Mr Riaz Phillips

Mr Riaz Phillips is a rarity in food journalism. In fact, he would likely resent the association. In an industry obsessed with the new, and one often influenced by trends dictated by Western-dominated editorial and social teams (in late August, Vittles founder Mr Jonathan Nunn tweeted, “More pasta restaurants were reviewed in the UK this year than Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Chinese, Korean, Thai, Japanese, east and west African and Caribbean restaurants combined”), Mr Phillips shines a light on food cooked by black and ethnic minority communities.

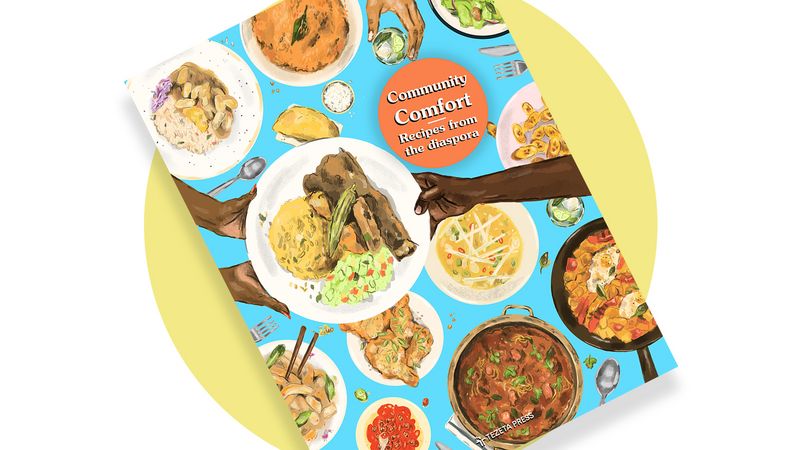

He is less interested in plates of food which generate Instagram likes, more in the how and why behind high-quality dishes and ingredients served up in kitchens that have nourished and comforted communities for generations, but have rarely garnered any sort of attention. His first project was Belly Full – a book he self-published in November 2016 – which investigated the people, flavours and hubs that make up Caribbean cooking in the UK (most of Mr Riaz’s family originate from Jamaica and the Caribbean). And he recently made his name with Community Comfort, an e-book that features recipes from more than 100 black and ethnic minority kitchens.

Standouts include Ms Ruby Tandoh’s leek linguine, a buttermilk fried chicken recipe by 12:51’s Mr James Cochran, okra soup by Mr Akudo Agokei and a Jamaican stew recipe from Mr Phillips himself. The proceeds of this latest book go to the Majonzi fund charity, which helps families affected by Covid-19 in black and ethnic minority communities, which have been disproportionately affected by the virus.

With a new edition of his Belly Full book expected later this year, we caught up with him on the phone from his current base in Berlin to talk about his approach to documenting food and how his work sits in the broader food media landscape in 2020.

Mr Akudo Agokei. Photograph courtesy of Mr Akudo Agokei

Nigerian okra soup. Photograph courtesy of Mr Akudo Agokei

Let’s start by taking about your background…

I was born in Homerton, in east London. I grew up between there and north London. All my family are from Jamaica, well – they’re all from the Caribbean.

When did you start documenting food?

When I was 27, a couple of years ago, I decided I wanted to go back to Jamaica and explore, so I went for three months. I’m always taking pictures, videos and noting down ideas. I’m inspired by my surroundings. I did a few journalist articles for Vice and made a bunch of videos. I did some volunteering, too, and exploring – getting to know the country again.

What role does the collation of recipes have in your work?

I was less interested in recipes and more so the stories behind the food and why people cook – its origins and the historical narratives. For example, I got interested in how certain fruits and vegetables come from West Africa, certain herbs and spices come from India and end up in the Caribbean, and how people from those regions came to the Caribbean.

**Is this thinking at the heart of **Community Comfort?

Yeah, I guess I was talking about how community is at the root of a lot of food. When people from the Caribbean came to England for work after WWII…

The Windrush Generation?

Yeah, exactly – they brought their food with them, so it’s another chapter in the story of this food movement, which I’m already fascinated by. In my book, I cover people from Turkey, Pakistan, all over the world who are based in London and have equally strong communities. In Community Comfort, I wanted to celebrate food that has been in the UK for decades, but hasn’t had good representation. A lot of people are bored of conversations around mainstream food now. I rate some of these cooks so highly they should be mega stars, but the system in play doesn’t really allow for that.

I read a piece by Ms Melissa Thompson earlier this year which talked about how underrepresented African and Caribbean restaurants are in food media…

A lot of publications don’t have much of a writer base that hail from those regions. Also, there has always been a bias of representation against regions of the world that are rooted in poverty and never shown in the same esteem or sophistication as places in Europe or in certain parts of Asia. So, inherently, when you ask 20 or so people who are from the same background where their favourite restaurants are, it’s going to omit a whole swathe of places. If they had one person of Caribbean descent, it would change the mix of topics to discuss.

Duck and bean stew by Mr Santiago Lastra. Photograph courtesy of Tezeta Press

Very few mainstream restaurant critics aren’t white.

I came at this whole thing from a very different perspective. I never really planned to be a food writer or a journalist, I just had an idea for a project I wanted to do a few years ago. I’m not really one to complain about things. By now we know what the structure of these different industries are, we know who’s represented at the editor, manager positions. If you wanted to you could tweet or write an article about a new uproar. For me, it’s better to spend time working on different projects to highlight representation from my side.

**Do you think your work is intrinsically political? **

A book in the UK with all people of minority backgrounds isn’t something that’s been done. It’s very much politically charged. It is about saying these are 100 amazing chefs, but it is also saying these communities have been in this country for generations and been ignored. What usually happens is: something in the food world pops up and a few magazines claim that they discovered it, or that it’s new, or fresh, and it’s… not.

There are a lot of food writers writing about food that they don’t necessarily understand. What do you think about that?

It’s tricky. The food industry has become such a cash cow, almost. It’s spawned all these offshoots, guide websites, blogs – people are in a hurry to write about places. A lot of the time they can be a disservice. Obviously, Britain is a majority white country, so it makes sense that those people would dominate the roster of food writers. There are some really good writers who understand food and can convey it to a wider audience. But lazy journalism and food writing is an issue. They don’t interact with the food or the people behind the food.

**How important are these conversations in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement? **

I think it’s very important, especially in London. Moments to slow down, sit down and catch up are few and far between. For Caribbean people, the epicentre of that is food places. That’s why writing about them is important. When I noticed that there are places that have been opened since the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s never mentioned by magazines and newspapers, I had to do something about it. A bunch of the places I wrote about in my first Belly Full book have since closed down.

**Could you talk about your new edition of **Belly Full?

I was debating whether I should just reprint the original because a lot of people like the format and stories. But the whole point was you could also go to the places. With some of them closing, it seemed like a relic piece. While it’s great to celebrate the older places, it’s also important to show the next generation who are carrying it forward with their own ideas – being one step removed from the Caribbean, how they relate to the islands, their family and what inspired them to carry on the food, culture and legacy.

What are some of your favourite spots?

It’s hard to pick favourites. Some days I feel like roti, Trinidadian food, so I’ll go to Roti Stop [in Stoke Newtington]. Or sometimes I want jerk chicken, so I’ll go to JB’s in Peckham or Smokey Jerkey in New Cross. Sometimes I feel like vegan food, so I’ll go to Eat Of Eden in Brixton. It depends.

Is the guy from Roti Stop in Belly Full_?_

His name is Bernard and he is from Trinidad. He moved to England some decades ago and he started off in the Trinidad party scene in London, which sounds like it was amazing – loads of raves and club nights. He would cook at home, drive to the raves and sell it out of the back of his car. He became well known through that. There weren’t many places to get Trinidad food and there still aren’t.

That story is the antithesis of what a lot of modern food journalism concerns itself with.

Yeah, I started out with the mindset of being the complete antithesis of trends. For example, I went out of my way to visit Old Trafford Bakery – a bakery in Manchester that has been open since the 1960s. There’s Horizon Foods, a big warehouse in north London – they do thousands of rotis a day. There is nothing Instagrammable about that place, it’s a little plastic door to the side of a warehouse, but that food is easily better than most food in London. At a fraction of the price. A lot of people from minorities don’t have the luxury of tile walls or neon lights – fancy fringe things that people think are more important than the food and the people.

If you strip everything away, is the main purpose of food comfort and nostalgia?

That’s one narrative to it. When I first started I just made a straight-up history book about UK Caribbean heritage and diaspora, but I knew if I did it through the guise of food, I’d be able to get it to a wider audience. Food is all of those things you mentioned – nostalgia, comfort, community, culture – but then there are other topics such as economics, migration, politics. You can talk about pretty much everything through the lens of food and the people behind it.