THE JOURNAL

These days, you’d be hard-pressed to find a brand that wasn’t keen to espouse its commitment to the planet. With collective levels of climate anxiety piqued by every UN doom claxon and a burgeoning awareness about our personal footprints, it’s simply good business sense to be – or to be seen to be – green. Still, with even the most climate-unfriendly businesses getting in on the greenwashing act, it’s not unusual for consumers to feel sceptical at worst, and bewildered at best, every time they endeavour to make a “conscious” purchase.

Dig a little deeper, however, and you’ll discover a growing community of independent craftsmen who are championing a slower, more mindful approach to making in a way that feels authentic, optimistic and uncomplicated. Best of all, they’re producing exquisitely engineered, forward-thinking pieces you’d actually want to own. In celebration of World Earth Day, we dropped by the workshops and studio spaces of four sustainably driven makers in London to learn more about their craft and creative processes.

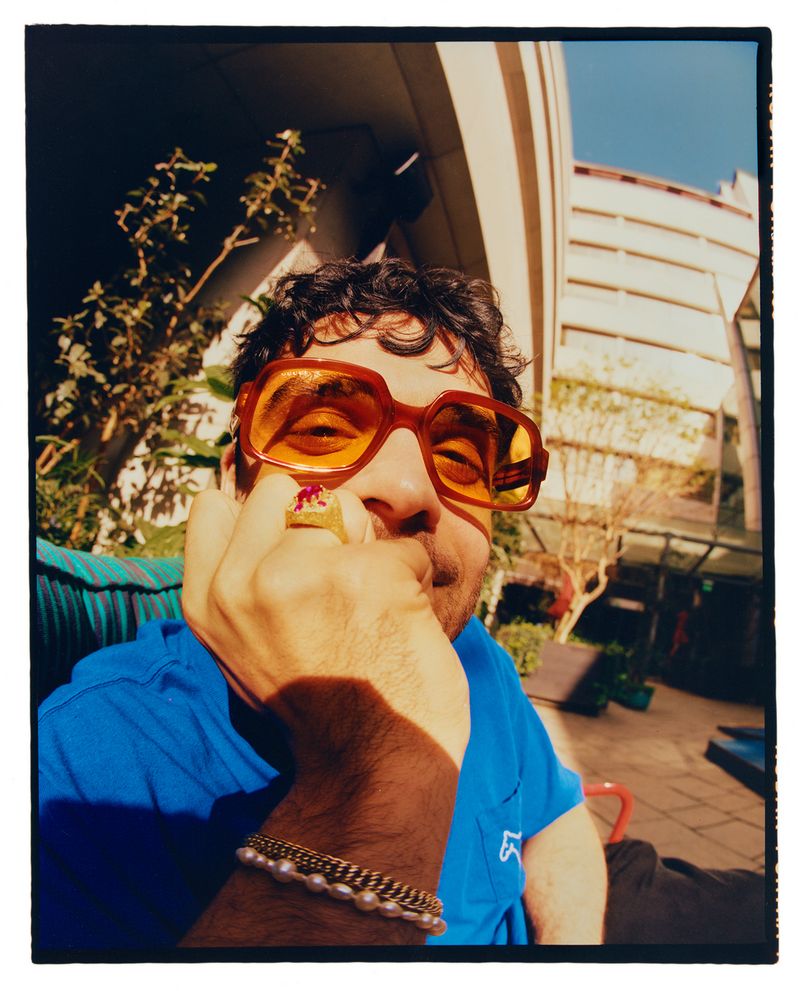

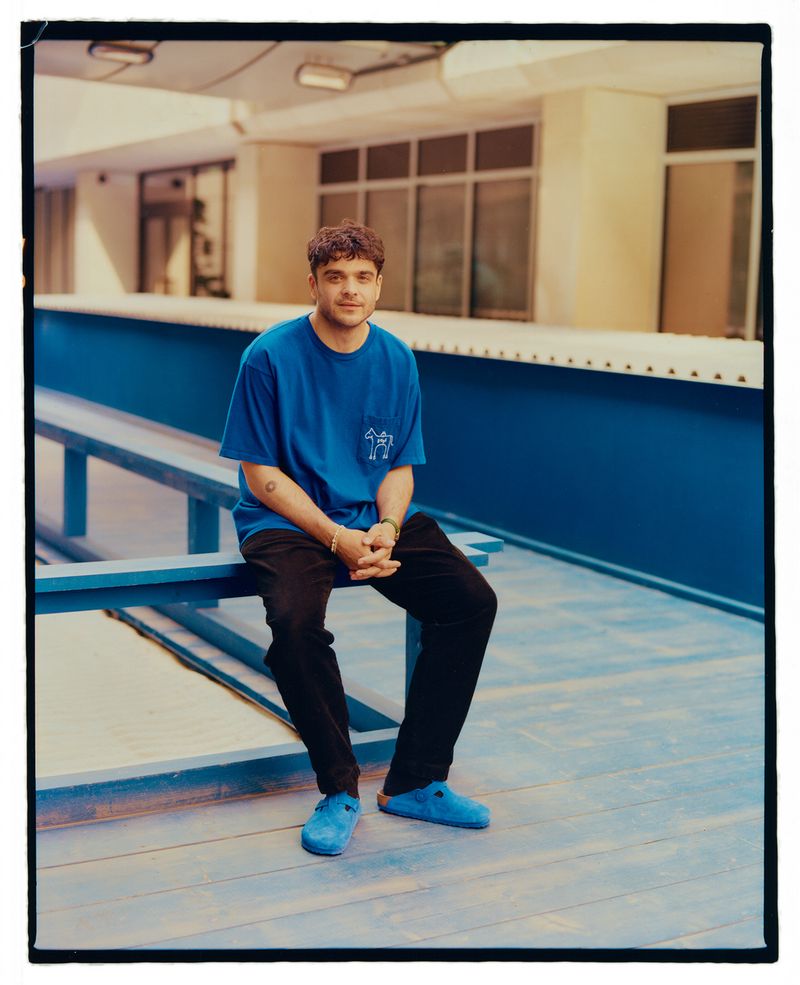

The jeweller

Mr Bleue Burnham

Before teaching himself how to craft jewellery and setting up his eponymous label in 2018, Mr Bleue Burnham worked as head of sustainability at Oliver Spencer, having graduated with a degree in the subject. Today, alongside a tight-knit team of jewellers, he creates rings and pendants from recycled precious metals and lab-grown gemstones at his studio space in 180 Strand.

Describe how you make your jewellery.

It’s called lost-wax casting. You hand-carve pieces out of wax, place them in a plaster cast, take the wax out so you’re left with a negative impression and then pour the metal inside it. I started out doing that and then I realised I wanted to use gemstones. I found out there was this method called pre-casting where you could set gemstones in wax. It’s a fairly unused method and there wasn’t much information on the internet, so I spent two years practising how to do it myself.

Where do you find inspiration?

There’s always a narrative tied to nature. Our latest collection is based around a book called The Secret Life Of Plants, which is a seminal piece of literature from the 1970s that looked at all the deeper intelligence of the plant world. I like to think that the way we create jewellery now is similar to how you’d view a tree. If you look at it in its entirety, it’s beautiful, but then if you go a bit closer and you look at the bark, there’s all these little dimples and nuances and imperfections you don’t notice at first.

How do you incorporate responsible practices into your work?

It’s actually much easier to do things in an environmentally effective way as a jewellery brand than it is a clothing brand. The main reason is your most used material – precious metal – is easy to recycle and it’s easy to get in recycled form from a refiner. With gemstones, however, the supply chain is so convoluted and untransparent. I knew we needed to use sapphires because they’re the only stones that can withstand the heat in casting, so we started looking into lab-created stones. It’s literally like a two-way transaction. The factory makes the stones, we buy them and there’s not like all these layers to the supply chain.

Internally, there’s a lot of smaller areas where we’re focusing on footprint reduction, so looking at things such as packaging as well as the energy use in our casting process now, which is all from renewable sources, and how we’re transporting jewellery around London, which is either done by bicycle or electric car. We’ve also set up a charity called the Natural Community Trust, which is still in its incubation period but will be based around supporting solutions to the climate crisis, predominantly through the arts and creativity and agriculture.

Who are your biggest design influences?

Olafur Eliasson. He’s my favourite artist. His work is very engaging and immersive, which I think is not only a nice way to enjoy art, but it’s also a very powerful way to enjoy art. It all has a deeper meaning to it, often connected to the environmental health of the planet, but it also has the beauty and the enjoyability factor.

Who would you love to see wearing your pieces?

Top of the list, A$AP Rocky. And I would love to see Frank Ocean in my jewellery as well. He’s an incredible creative and to have someone of that ability enter the jewellery world [with Homer, Ocean’s luxury brand] makes me happy, as I know he’s going to be putting out good stuff.

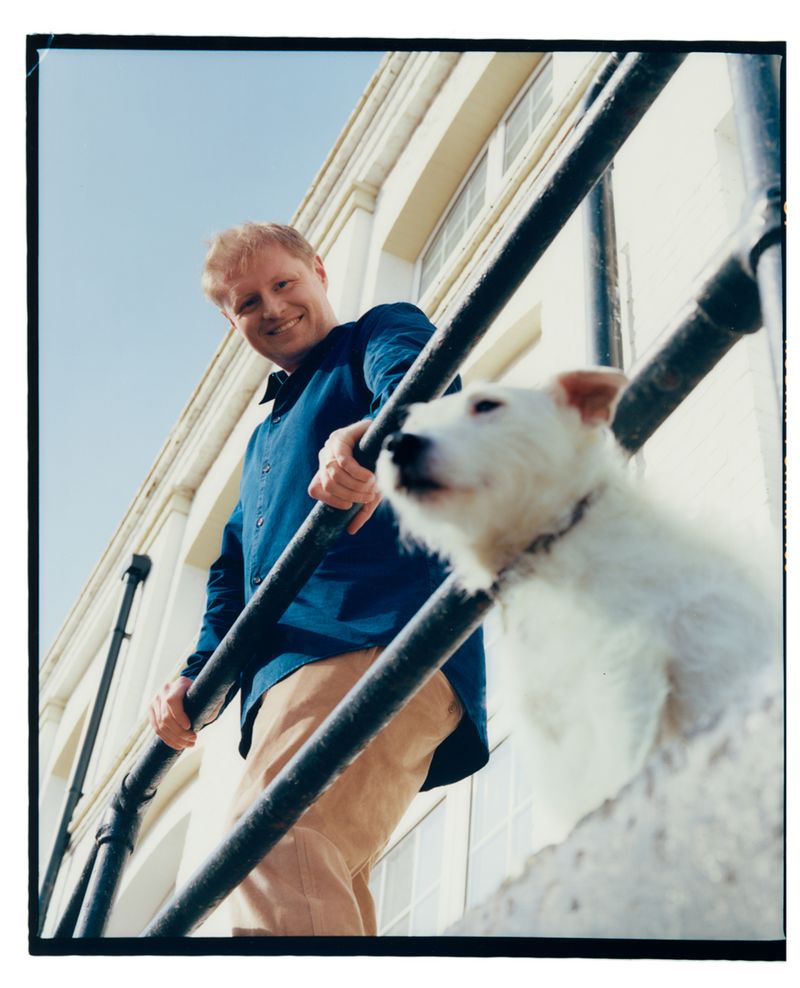

The woodworker

Mr Sebastian Cox

Award-winning woodworker and environmentalist Mr Sebastian Cox wants to challenge everything you thought you knew about trees, most notably why felling them isn’t all bad news and why replanting isn’t necessarily the answer. In years past, his design talents and environmental know-how have been tapped by everyone from Burberry to deVOL Kitchens to the V&A.

You’re famously in favour of chopping down trees and against replanting. Can you explain?

We have our own woodland and we manage it in a way that favours natural regeneration of trees. I feel sometimes it’s wasted effort and energy to plant trees, because if you take, say, a field that you’re farming and you leave it, in 20 years it’ll be a young woodland. So we don’t need to plant trees. There are animals that do that for us. The notion of tree planting is a little bit of an indication of how we as a species have become so detached from nature that we have to garden it.

Also, when you fell a tree, as long as you don’t burn that tree or let that tree rot, the carbon present remains stored in the wood, and then carbon is also reabsorbed by the new growth. So every time you do that, you effectively suck more CO2 out the atmosphere. Felling trees can also let light into a wood, which will attract insects and then that will attract mammals and the whole woodland will become more biodiverse.

How does your passion for sustainability inform your work?

Ninety per cent of the wood that we use in the UK is imported, whereas we have our own woodland, so we’re reducing our carbon footprint and our carbon miles in that way. By using wood from continually managed forests, we’re locking up carbon in people’s homes. Our aim every year is to store 100 tonnes of CO2 in the wood that we make our furniture with. And because wood is such an effective store of carbon and such a brilliantly efficient material to process, even with the shipping and manufacturing energy, if you buy a dining table from us, it will still be carbon negative by the time it arrives in your home.

What sort of projects are you working on at the moment?

We’ve just had quite a substantial commission from Harewood House in Yorkshire for its art biennial. This year’s theme is Radical Acts and our radical act was to go there, chop down trees, which most people recoil at, and then build a Sylvascope [treehouse]. The idea is that it’s a structure from which you can see the benefit of cutting down those trees so that in the next few years, the woodland will regenerate.

How would you sum up the Sebastian Cox style?

I would describe it as having truth to materials. In that sense, it’s very inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th century. I’m sensitively looking at what nature has given us and then trying to make that relevant and appealing to modern people who perhaps live in an urban environment.

What’s the most exciting project you’ve worked on to date?

Quite early on in my career, I had a commission from Terence Conran, where I made a desk that was sort of like a cocoon in which he could shut himself away. And then we worked with Christopher Bailey on a series of pieces for Burberry. We made a personal piece for Christopher for his leaving gift. It was a chest that contained gifts from other people and the idea was that it had secret drawers and secret compartments with keys and locks and he would gradually discover all the things that people had gifted him. That was amazing, actually. He wrote me such a lovely letter.

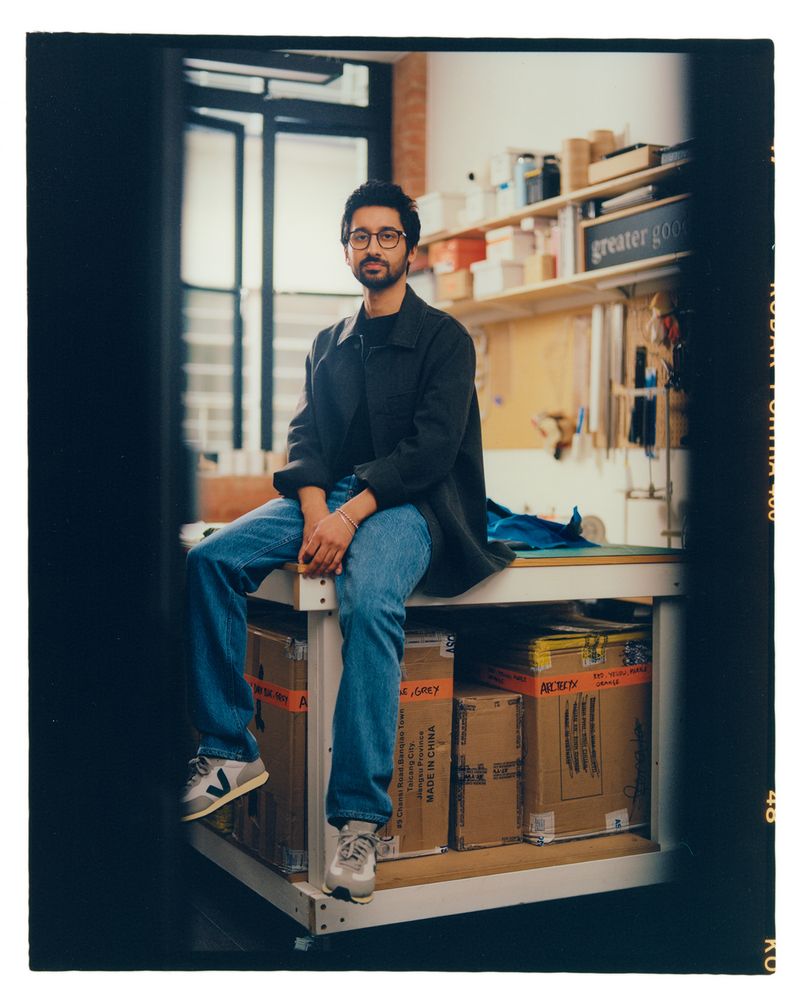

The upcycler

Mr Jaimus Tailor

Mr Jaimus Tailor’s Greater Goods is an upcycled accessories label whose USP is breathing new life into battered technical outerwear by reworking it as desirable, sell-out tote bags. Since launching, he’s racked up a dedicated customer base that spans discerning outdoorsmen in need of hard-wearing, weatherproof gear and streetwear types riding the Gorpcore wave. He runs his one-man operation from Bounds Green in north London.

How did Greater Goods come about?

Greater Goods was initially pure carpentry. I’d find wood in my local area and make it into bits of furniture, shelves and benches, tables, anything pretty much, and sell it on. But I’d always wanted to learn how to sew and so in 2019 I bought a sewing machine off eBay, watched videos on YouTube and started learning how to make simple things and take things apart.

How did the upcycling element come into it?

I never went into this thinking, “I want to be sustainable.” It just makes sense to me. Even with the carpentry, I wasn’t buying wood. I was just finding things. When I started sewing, I cut up a North Face jacket that I couldn’t sell on eBay because it was so beaten up and I just thought I’d use the fabric. The one issue with upcycling is that it’s almost double the workload, because you have to take things apart carefully, you’re limited to a certain range of fabrics, it’s already cut in. It almost sets its own design brief. But I quite like that problem-solving element.

How did you go from that first bag to your current business?

I was working at a store in London and I brought in my own bag and people really liked it and encouraged me to sell them. I shared it on a few Facebook groups and it got a good response, with people asking to buy them, so I thought I’d just make a small collection of 15 or so bags. At the beginning, I was just looking on eBay and Depop. I’d type in “Damaged” and then filter the category down to outerwear. And one jacket goes a long way. Then I just did the usual of making a Shopify, promoted it on Instagram and was fortunate to get great press.

How do you make your bags?

As the business progressed and clients wanted to see what I was creating before I made it, I had to start sketching. The thing with upcycling, though, is that it’s a process that develops as you’re making. Once you’ve taken apart the jacket and sewn bits together, you often have new ideas. A sketch is good to get your thoughts on paper, so you’re not overburdened with ideas, but once you get making, it’s often quite nice to think on the spot and adapt. And because I don’t have to OK a design with someone else, I can just be quite open and fluid with what I’m doing.

Proudest achievement so far?

I would say the first Arc’teryx collection I did for the London store. It was a big collection and a lot of firsts. Initially, they just asked me to make product, but then I suggested creating a look book, a zine, doing in-store displays, so we kind of pushed it. And I made that whole collection in my bedroom and took it on with my fingers crossed, but it was great. It showed me what’s possible, and to have that trust from a brand after just a few Instagram conversations was amazing.

The artist

Mr James Shaw

A childhood spent building structures from Lego blocks and moulding objects out of mud and Play-Doh primed Mr James Shaw for his career as an artist and designer. He did a master’s at the Royal College Art in London, where he developed his distinctive design technique, which involves funnelling post-consumer plastic waste into an extruder gun and transforming it into squidgy, sculptural forms. He shares his machinery-filled workshop in Walworth, southeast London, with a jewellery designer, a furniture-maker and his assistant.

You have such a distinct design aesthetic. How would you describe it?

I guess it’s quite blobby. There’s often a complexity of surface and a kind of organic form. I’m from a little town in Devon and I always think that maybe the trees and rocks round there have got a lot to do with my aesthetic. But I also think it’s something that’s developed from the materials and processes themselves. It feels like what they naturally want to do, so rather than fighting it, I’ll just embrace it.

How did the no-waste element come into your work?

I think that was always there. Even when I was doing my foundation course, I was street-combing all the time and looking for bits of broken furniture or bits and bobs that I could use to make stuff out of. I’ve always been interested in trying to create a sustainable way of working and making things, but in a way it’s more implicit than anything else. It’s always going to be there because to me it just makes sense.

Where do you source materials for your creations?

I use a variety of suppliers from around the UK. It’s kind of just a matter of calling people and finding out if they’ve got anything they’re willing to sell me. When I started out, people were willing to give me stuff, but it would be a tonne of material at a time because that’s the smallest quantity that these companies would be willing to deal with. I’d go to London’s main recycling plant in Dagenham, which mostly processed HTPE – so milk bottles, shampoo bottles, food trays, things like that. I’d basically turn up to the lorry park in a little [rental] Zipvan, trying to fit a forklift into the back and then shovel it out at the other end.

Who are the designers and makers you most admire?

Loads, really. I’ve always admired Phyllida Barlow. She’s a British sculptor who taught at the Slade [School of Art] for a long time. Or there are people like George Nakashima, the American woodworker, whose stuff is really fantastic. Right now, I’ve got a Gerrit Rietveld book on my desk. He’s a Dutch furniture-maker who I think has a really interesting way of approaching structure and form. Lots of material intelligence in there.

Which projects are you most proud of?

It’s usually the thing I’ve done most recently. I’ve just finished a project with the filmmaker William Glass – an abstract film based on the movement of materials – which is going to be part of an exhibition at Studio Voltaire in London, and I’m really excited about it. But then there are little things as well, such as our candle holders and toilet-roll holders. We’ve turned the toilet-roll holder into A Thing. I’m quite proud of being able to take something so mundane and overlooked and make it into a desirable item.