THE JOURNAL

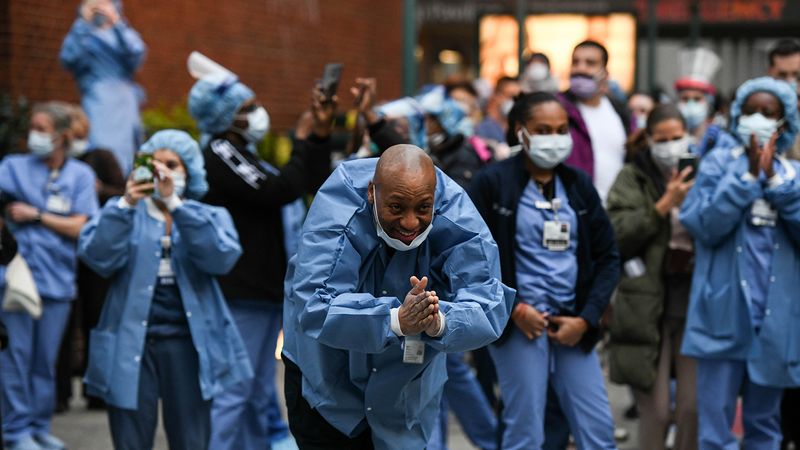

Lenox Hill hospital health workers in the Upper East Side, thank New Yorkers that clap for those fighting the coronavirus in what has become a nightly ritual all over the city, 10 April, 2020. Photograph by Mr Miguel Juarez Lugo/ZUMA Wire/Shutterstock

“When you want to know how things really work,” Mr William Gibson wrote, in Zero History (which is, coincidentally, the greatest novel ever written about clothes shopping), “study them when they’re coming apart.” So, maybe now is the best time possible to take a look at our social fabric, the matrix of our interconnectedness, while it is pulled taut unto the point of fraying to leave all that space for social distancing.

Maybe now, with much of the world on lockdown, while we see surges in fear, in irrationality (and toilet-paper shopping), it is a good time to consider why, for instance, neighbourliness, in our culture, is often made out to be a kind of sentimental ickiness – Mr Rogers parodied as Ned Flanders. With the sudden drop-off of interpersonal human interaction, we might wonder why we lock up every inch of our personal interest like Gramercy Park, with keys given only to those closest to us. Or, pre-corona, was it all an act – standing so that others may sit, making space, time and consideration for others? And in our PoCo world, will we revert to some sort of primeval state of selfishness and scorn for our fellow man?

Every evening at 7.00pm, as hospital shifts are turning over and exhausted frontline workers are either making their way into or out of the trauma wards that hospitals have become, all of my neighbours stop what they are doing – which is to say they stop, for a moment, shouting obscenities at and threatening to call the cops on one another – and join in a joyous and full-throated celebration of our healthcare workers. It is a really sublime and emotional moment, every night, but it is only an intermission in what feels like a daily deluge of rudeness and disquiet shouted from every direction.

Granted, I live in New York, a city that is not exactly world-renowned for the general cuddliness of its citizenry. But in New York, as Ms Fran Lebowitz said in a story I did with her a few years ago, “we have something you don’t hear about anymore: we have tolerance”. “Tolerance,” she said, “is really a better thing than understanding, because it doesn’t agitate against human nature, like love does. Or acceptance or understanding… But letting people get on and off the 6 train without stabbing each other, that’s good.”

Even if it is a bit raucous, rude and brash, in other words, New York is, in normal times at least, somewhat neighbourly. In a crisis, though, New York is something else: a commune of kindness like something out of fairy tales. As we hunker down before and after hurricanes and floods and brownouts and even terrorist attacks, good Samaritans are out in droves, checking on the most vulnerable, bringing food, supplies, care, comfort – in normal crises, New Yorkers are the greatest neighbours imaginable.

“Failures of kindness are not the result of some innate selfishness, but in fact a symptom of our culture of individualism”

But what about now? What happens to a citizenry during a crisis in which our very proximity to neighbours, friends, colleagues and classmates is framed not only as the vulnerability it always was, but as risk? When exposure to fellow man is potentially hazardous to both parties, what will that do to kindness? As Ms Lebowitz recently told The New Yorker, now “people are afraid of people”. “The doormen are terrified of us,” she said. “They have a rope around the concierge desk. It looks like Studio 54.” In New York, at the moment, we seem to be recoiling from one another in fear, vampires (or those leaving Studio 54) greeting the sunlight. “After September 11,” Ms Lebowitz said, “I was on the street 24 hours a day, and I was riveted by the things I saw… But now it’s just sad.”

In their great book On Kindness, the psychologist Mr Adam Phillips and the historian Ms Barbara Taylor argue that our present (meaning even pre-corona) failures of kindness are not the result of some innate selfishness we are always told we have, but in fact a symptom of our culture of individualism. We used to be kind, they say, but we’ve had it stamped out of us, personally, since childhood, and culturally, since perhaps Leviathan, Mr Thomas Hobbes’ 1651 “ur-text of the new individualism,” as they call it. “Kindness – that is, the ability to bear the vulnerability of others, and therefore of oneself – has become a sign of weakness,” they write.

Of course, even Mr Hobbes couldn’t imagine the dissociative effects of our seemingly ethereal existences online. I doubt even he could imagine the cruelty of the comments section. But online, whether through benefits selling artists’ prints, or with restaurants fielding donations for their staffs, we have seen some of the greatest displays of generosity and care during this time. Charity may be our best attempt at kindness at the moment, but it does raise the question of whether our care and consideration for our fellow man has all become abstract, vague – a general concern for healthcare workers, say – while we still scowl at our neighbours behind our masks.

As Mr Phillips and Ms Taylor write, our lack of kindness is not some inevitability; we are not reverting to some primitive state. On the contrary. The ancients, for example, held kindness in great regard. Mr Marcus Aurelius, for one, Stoic poet emperor of Rome, thought it “the manliest” and the highest purpose of humanity (and, so, the most fulfilling mode of behaviour). For the early philosophers, kindliness wasn’t somehow against our nature, the high road when we would so prefer to slink into decadent self-absorption. Even the Epicureans believed it was the path to better living.

But kindness does require some bravery – to continue opening ourselves to the needs and fears of others. “Real kindness is an exchange with essentially unpredictable consequences,” Mr Phillips and Ms Taylor write. “It is a risk precisely because it mingles our needs and desires with the needs and desires of others, in a way that so-called self-interest never can.”

But, they add, “To live well, we must be able to imaginatively identify with other people and allow them to identify with us. Unkindness involves a failure of the imagination so acute that it threatens not just our happiness but our sanity… The self without sympathetic attachments is either a fiction or a lunatic.”

So many examples of these unsympathetic lunatics roam free at the moment I needn’t bother pointing you to any in particular. But what if they are the outliers? What if this reset gives us occasion to recognise and re-contextualise decency, neighbourliness and kindness to others, not as sentimental softness, but as the honourable behaviour of the good (in accord with our true nature, as writer Mr George Saunders suggested when he said, “What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness”)?

We talk a lot about putting into practice now those patterns of behaviour that will carry us out of isolation and into our post-corona reality (whether it is journalling, foam rolling or shopping more conscientiously). What if we really took this in-it-together sloganeering to heart and treated our neighbours, friends and fellow humans not as competitors in the Thunderdome, but as we should like to be treated ourselves?

What if, (ironically) alone in isolation, we found a way to wind down our deference to the cult of individuality, and made some room in the gated garden of our care and consideration, not only for the abstract, platonic heroes on the frontlines, but for the real-life humans we see before us? That would certainly be deserving of a round of applause.