THE JOURNAL

Why the fermented tea will be your new favourite drink.

If you frequent the expensive sort of yoga studio, or organic grocery store, or Instagram account, chances are you will have come across kombucha. In the past five years or so, the lightly effervescent fermented tea drink has taken its place among such K’s as kale, kimchi and kefir at the 21st-century lifestyle vanguard. Its apparently miraculous side-effects – it transforms your gut flora! It improves cognitive function! It makes excuses for unwanted lipstick on your collar! – have helped to catapult what was once an obscure hippy drink to the forefront of the non-alcoholic drinks market. Kombucha sales were valued at $1.06bn in 2016, according to Zion Market Research. By 2022, that number is predicted to reach $2.5bn. And, what’s more, kombucha is delicious. The good brands – Jarr, Real Kombucha, LA – combine a tongue-tingling tartness with a funky depth of flavour. As Mr Michael Pollan observes in his book, Cooked, it tends to be fermented foods that produce the strongest reactions and the fiercest cults. Think: wine, beer, chocolate, blue cheese, Marmite, sauerkraut, sourdough, chorizo, miso and now kombucha.

Where did kombucha originate?

It’s thought to have originated in northeast China in about 220BC. “It was most likely created by accident,” says Mr Adam Vanni, 30, a Los Angeles native who brews Jarr Kombucha in a brewery out in Hackney Wick, east London. “Someone probably left out some tea in the sun, sweetened with honey which was the only natural source of sweetness back then. They must have returned to it, found it full of mould but decided to drink it all the same.” It’s still found in China and Russia, but the drink also has a well-developed Russian line (it’s similar to kvass, a fermented bread drink that’s surely due for a hipster revival, too).

How is it made?

In Russia, it’s known as chainiy grib, or “tea mushroom” on account of the large disc of fungus (or “Scoby”, standing for “symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast”) that you’d add to a tureen of sweetened tea. Over a week or two, this weird jelly mushroom disc thing sits on top of the tea, occasioning an aerobic fermentation, eating up all the sugars and dispensing beneficial bacteria. Then you remove the disc, add extra flavours (if desired) and decant into bottles for a second anaerobic fermentation. In Soviet times, this was a popular homemade alternative to western soft drinks like Coke and Fanta.

When did it become popular?

Modern kombucha really took off in California in the 1960s, where it was known as “brewed tea” and touted as a New Age panacea for arthritis, constipation, psoriasis, modernity, you name it. It began to find an appreciative audience beyond yoga studios and head shops in the 2000s, especially when the big brands started adding extra sugar and flavourings and pitching kombucha as a healthier alternative to soft drinks.

Why drink it?

Even if some of the health claims made of kombucha are exaggerated, it’s still lower in sugar than most soft drinks and its probiotics would appear to help the gut more than, say, Mountain Dew. And if you are off the sauce for whatever reason, it’s a bit of a godsend. “I virtually quit alcohol four or five years ago,” says Mr David Begg, founder of the London-based Real Kombucha. “[Kombucha] was the thing that I wanted to be drinking with a meal, in a pub, when I got home from work – every time I wanted to be drinking wine. It managed to fill that gap.” This has a lot to do with the way it’s made. ”It’s a fermented drink, a bit like beer and wine. It has the same amount of complexity. This is the potentially the only non-alcoholic drink that sits alongside wines.”

What to drink with it?

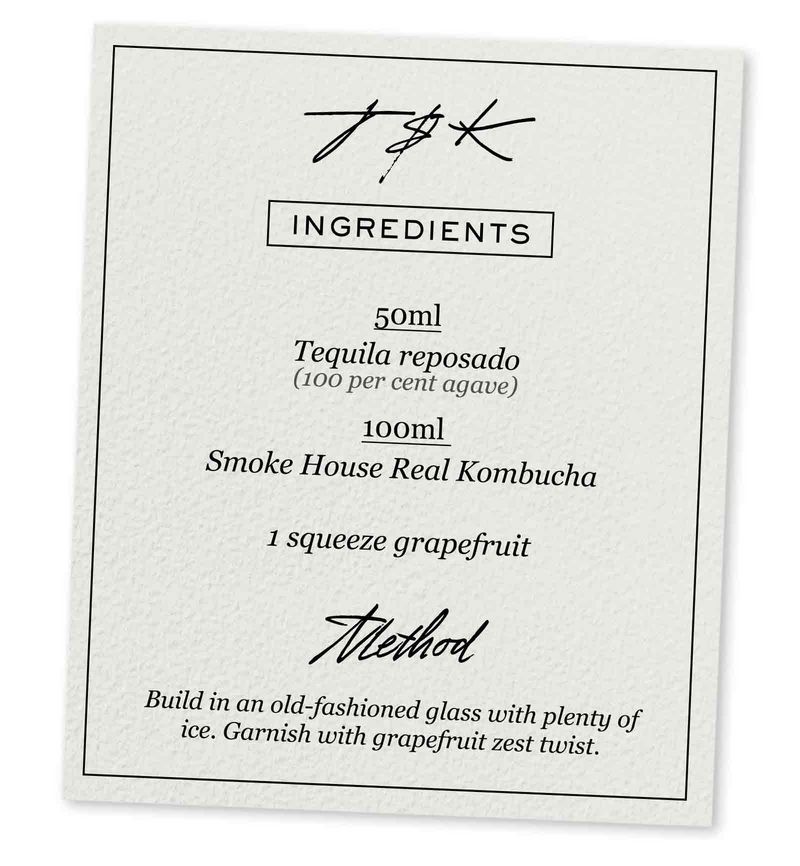

Mr Begg places the emphasis on the different tea varietals that he uses as a base, a bit like a winemaker might do with grapes. His Royal Flush kombucha is brewed with early Darjeeling tea and has a light acidity that makes it go well with fish a bit like a chardonnay. The Smoke House, meanwhile, is his pinot noir, made with the high altitude Yunnan tree. “It has a delicate smokiness and a maltiness, too. When it’s brewed, you get these wonderful apple, caramel and malt flavours – it goes very well with dark meats and smoked meats. The sommelier at the Fat Duck has actually paired it with one of their mushroom dishes in place of a wine.”

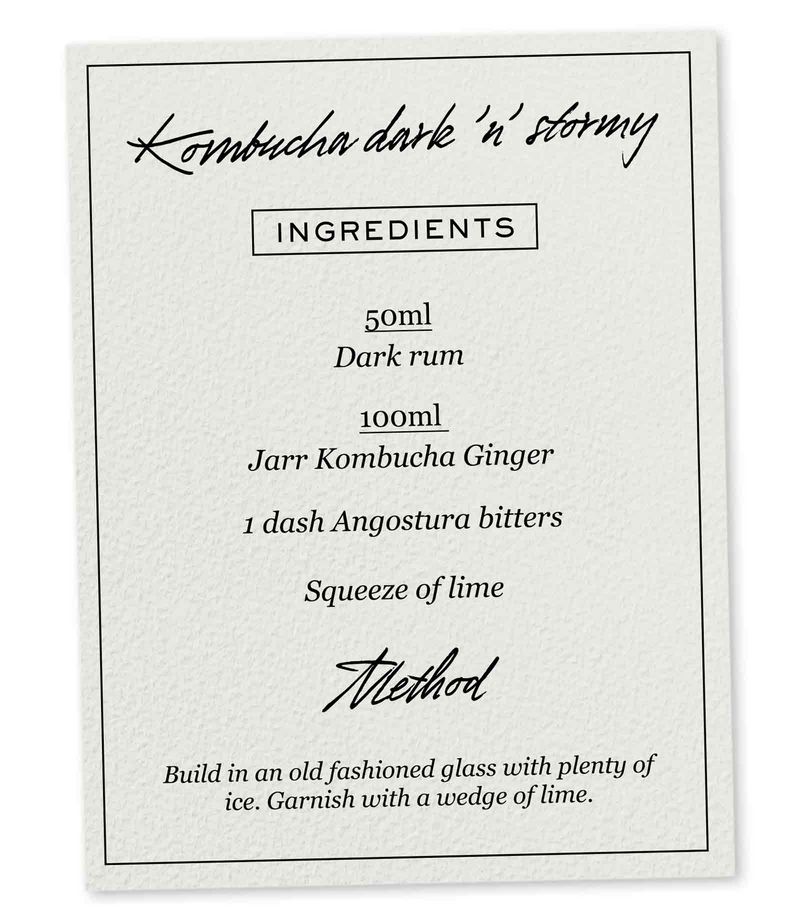

Still, just because it works as a non-alcoholic alternative to booze is no reason not to add booze to it. Indeed, Bristol’s Kombucha has claim to be the first truly alcoholic kombucha, albeit at a mere 1.6 per cent. Mr Vanni has been working with the renowned mixologist Mr Alex Kratena to create a guayusa-based kombucha for use in cocktails. For the home bartender, he suggests mixing his own ginger kombucha with dark rum, and the passion fruit variant with light rum. Meanwhile, the plain flavours work well with gin in place of tonic. Or you could try adding tequila to Real Kombucha’s Smoke House. It’s good for you... promise.