THE JOURNAL

Messrs Ted Freeman, Buzz Aldrin, and Charlie Bassett experience zerogravity in Nasa’s KC135 aircraft. Photograph Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images courtesy of Taschen

On 20 July 1969, Mr Neil Armstrong famously said, “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Along with Messrs Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, the crew of Apollo 11 had successfully, for the first time ever, landed man on the Moon. It took a decade of tests and training, a staff of 400,000 engineers and scientists, a budget of billions and the most powerful rocket ever launched to answer President John F Kennedy’s call for a manned Moon landing by the end of the 1960s.

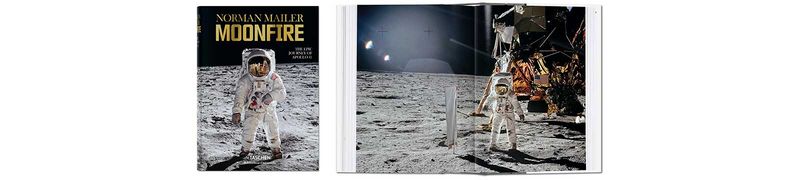

Half a century ago, this was the stuff of science fiction – an achievement that was nothing short of a miracle. Today, the feat is just as incredible. “Nowadays, there is more computing power in my fridge than there is in the machines that managed to take the astronauts up in Apollo 11,” writes Mr Colum McCann in his introductory essay to MoonFire: The Epic Journey Of Apollo 11, written by iconic American author and journalist Mr Norman Mailer.

Originally penned on assignment for LIFE Magazine – and published in 1970 as the book Of A Fire On The Moon – Mr Mailer’s philosophical account of the Apollo 11 mission has been updated to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Moon shot. Capturing the atmosphere of the time and the heroic feats of the astronauts that made history, Mr Mailer’s prose has been augmented with hundreds of photographs and maps from the Nasa vaults, as well as contributions from leading Apollo 11 experts. Here are three facts about the Moon landing that may have eluded you (until now).

An all-American affair?

Think of the Apollo 11 mission, and you think of pure, American achievement – Uncle Sam at his greatest. But it was actually the work of Mr Wernher von Braun, a German rocket engineer whose V-2 rockets had helped the Nazis terrorise London during WWII, that enabled the Saturn V rocket to propel Messrs Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins and their Apollo spacecraft to the Moon. Mr Von Braun was just one of 1,600 German scientists, engineers and technicians that were brought to the US after the war – as part of Operation Paperclip – to work for the US government, in an effort to get one up on the Soviets in the Space Race. Vorsprung durch technik, indeed.

Laurel and Hardy on the moon

While the mission was one of utmost seriousness and wonder, there were times where the mundanities of human nature crept in – to humorous effect. Mr Mailer details an exchange between Messrs Armstong, Aldrin and Mission Control, in which Houston and Mr Aldrin continually reminded Mr Armstrong of the need to pick up a sample of Moon rock and put it in his pocket – the contingency sample – in case the moonwalk had to be aborted early. He writes: “‘Right!’ Armstrong snapped. The irritability was so evident that the audience roared with laughter… Nagging was nagging, even on the Moon,” before concluding, “There were moments when Armstrong and Aldrin might just as well have been Laurel and Hardy in spacesuits.”

Space hacks

When Messrs Armstrong and Aldrin climbed back into the lunar module cabin after their EVA (extravehicular activity), their backpack-like PLSS (primary life support system) devices proved to be a problem. On entering the cabin, Mr Aldrin’s had broken off the little plastic pin on the ascent engine’s arming circuit breaker. This circuit would send electrical power to the engine that would lift the astronauts off the Moon, and by extension, back home to Earth. In short, they were stranded. Looking around for something to punch in the circuit breaker, they found that a felt-tipped pen fit into the slot perfectly. Crisis, averted.