THE JOURNAL

Forget fast fashion. These craftsmen refuse to do things the easy way.

Not too long ago, before it became a byword for overpriced groceries, the word “artisan” actually stood for something. In a world increasingly filled with mass-produced tat, it was a reminder of the emotional power of the small-batch, the traditional and the lovingly handcrafted. Just as Messrs William Morris and John Ruskin took a stand against the industrialisation of the late-Victorian era by founding the Arts and Crafts movement, so the humble artisan mounted his own small rebellion against modern-day mass-production.

Today, of course, “artisan” has been co-opted as a marketing buzzword and attached to so many products of spurious value that it has lost much of its original meaning. Such is the cliché surrounding the word that anyone who identifies as such leaves themselves exposed to parody – a point underlined by this week’s edition of The Tribes.

The artisanal spirit lives on, though, and in many ways has never been more relevant. In an era when anything can be mass-produced, even luxury goods, it’s inevitable that we place greater value on things in which we can perceive a degree of authenticity. After all, when anyone with a credit card can buy a case of Krug, what does luxury – a concept that’s forever been indivisible with exclusivity – even mean? Now, more than ever, we want to feel a connection with our belongings and the people who made them. We want something with a story, something with a soul.

There are few better places to witness this change taking place than in the world of style, where the rise of mass-produced fast fashion has made the latest trends accessible to all. Against this backdrop, a brand needs more than just a logo to stand apart. It needs something unique, something that by its very nature cannot be copied or mass-manufactured. And the following brands offer just that.

Every fledgling brand needs a good story, and there aren’t many better than the one about Mr Mike Amiri’s cashmere sweaters and the shotgun in the Californian desert. Back in the early days of his eponymous clothing brand, while he was still working out of the basement of a Thai restaurant on Sunset Boulevard, the Los Angeles designer met a guy in the Rose Bowl flea market who was selling vintage clothing that he’d blasted with shotgun pellets. OK, he thought. What would happen if I did this to cashmere?

AMIRI’s shotgun-blasted cashmere sweaters might be the perfect metaphor for a brand that meshes high luxury with the rebellious, rip-and-repair, rock’n’roll aesthetic of the US West Coast, but they’re far from the only example. Take the hugely popular denim range, for example, which is painstakingly deconstructed and embellished by teams in white lab coats and surgical gloves working from an atelier in Downtown LA. Or the one-of-a-kind leather jacket, painted with palm trees and studded with Swarovski crystals, that announced the brand’s arrival on MR PORTER in 2017. As Mr Amiri himself told us last year, “every piece is unique”.

Or try these

A relative newcomer to MR PORTER, Bleu de Chauffe launched as part of our recent Vive La France project, in which we shone a spotlight on some of the country’s most exciting casualwear designers. Based in Aveyron, southern France, the brand makes hard-wearing bags from canvas and vegetable-tanned leather, each signed and dated by the artisan that created it. That’s the crucial thing about Bleu de Chauffe: every one of its bags are made, from start to finish, by a single craftsperson. And while that might not sound particularly revolutionary, it is – in a quiet sort of way.

Contemporary mass-production is based on the division of labour, in which the manufacturing process is divided into a series of small tasks, each one carried out by an individual worker. In the case of a bag, for instance, you might have one person cutting the leather, one stitching the straps, one attaching the zips, and so on. It’s an efficient method, but it reduces workers to little more than cogs in a machine. Disillusioned and disconnected from the fruits of their labour, they can easily let their standards slip.

This is why companies such as Bleu de Chauffe matter: because they recognise that the best way to get a job done isn’t necessarily the most efficient. Yes, the bags take a little longer to make. Yes, you’re paying a little more. But what you get for your money is the peace of mind that comes from knowing that the artisan who made your bag – Anna, Morgane, Fabienne, or whoever it may have been – actually enjoys their job.

Or try these

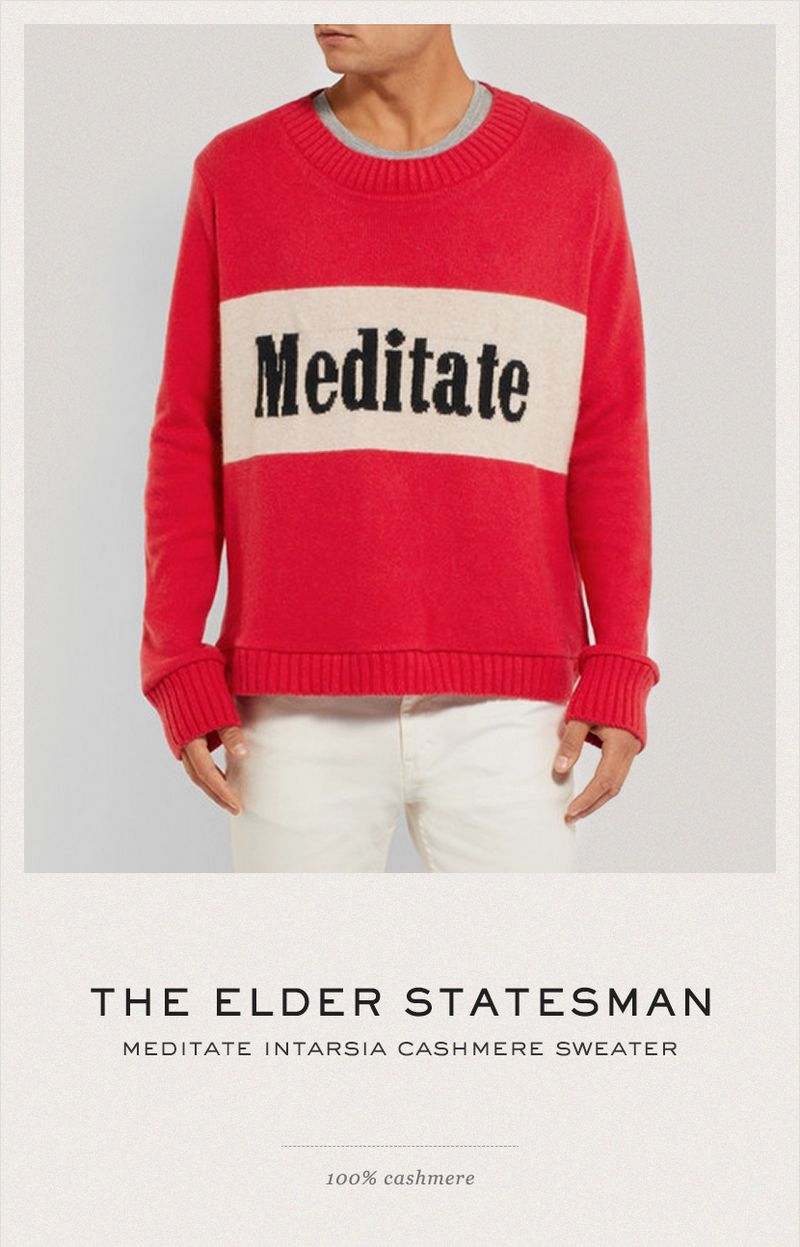

The Elder Statesman came about in much the same way as many companies do: a person wants a thing, can’t find it, decides to make it and then realises that there’s a market for it. In this case, the person was Mr Greg Chait and the thing was a cashmere blanket. After making a few for personal use – he sourced the cashmere from Mongolia and had it spun and woven into blankets by a specialist guild in Canada – the Los Angeles native decided to make a business of it, founding The Elder Statesman in 2007. His first run of blankets sold out almost immediately.

How could something so simple be such a hit? Mr Chait has a theory, and it involves doughnuts. “I would venture to say that 99 per cent of the people in the world like the taste of doughnuts,” he told Bloomberg in 2015. “I mean, it’s probably embedded into our DNA to be able to recognise things like that.” Cashmere is the sugary, high-fat treat of the fabric world, in other words. It’s something we experience on a primal level. In Mr Chait’s defence, though, not all doughnuts are created equal – and nor is cashmere. The Elder Statesman is a case in point. Its sweaters have a near-legendary reputation in the MR PORTER office, eliciting a similar reaction to what happens when a female colleague returns from maternity leave to show off her new baby. Crowds form, onlookers gaze adoringly... look, once you know how they feel, you’ll understand.

Or try these

Mr Hiroki Nakamura’s visvim is the ultimate cult menswear brand, fetishised by its followers for an uncompromising design philosophy that sees every last detail obsessed over, from the yarn used to spin the fabric of a garment to the buttons that finish it off. If you want a better idea of the mind-boggling level of thought that goes into it all, we highly recommend spending a couple of hours on the Dissertations page of visvim’s website, which features dozens of “product introspections” penned by Mr Nakamura himself on everything from Goodyear-welted shoes to vintage Japanese-paper fabrics.

You don’t have to be an expert in something to appreciate it, of course, and while visvim is undoubtedly the sort of brand that appeals to menswear obsessives – including Messrs John Mayer and Eric Clapton, apparently – there’s plenty for the casual consumer to enjoy about it, too. The brand’s shoes, in particular, are worth checking out. In 2001, Mr Nakamura was one of the first to bring artisanal techniques to the world of streetwear with the FBT sneaker, a Native American moccasin planted on an EVA midsole and Vibram sole, and he continues to blend traditional craftsmanship with a contemporary aesthetic to this day.

Or try these

It’s tempting to think of France’s De Bonne Facture as less of a menswear brand and more of a collaborative project, such is its dedication to championing its manufacturers. Attached to every garment is a tag with the name and location of the workshop where it was produced, along with a brief potted history. There are shirtmakers in Écueillé, jersey manufacturers in Guidel, knitting factories in Quimpier and many more, all of them tracked down by the brand’s founder, Ms Déborah Neuberg, through word of mouth, on obscure internet forums and at industry fairs. The fabrics are just as carefully sourced, with virgin wool from Italy’s famed Biella mills, organic cotton from Peru and Shetland wool from the remotest parts of Scotland.

Now, we know what you’re thinking: a passion for provenance and a dedication to transparency are all well and good, but they don’t count for much if the clothes aren’t great. To which all we have to say is: take a look at them. Ms Neuberg’s creative vision, realised by some of France’s most highly skilled artisans, has resulted in some of the most handsome menswear we’ve seen in a long time. Don’t miss the shearling jackets, which are sure to come into their own over the next couple of months once this blasted heatwave subsides.

Or try these

To anyone unfamiliar with the history of Japanese leathercraft, Blackmeans – a brand founded by a trio of hardcore punk fans and renowned for its stunning, high-end leather jackets – might not make a great deal of sense. After all, luxury and punk don’t usually go hand in hand. To get a better idea of what Blackmeans actually means, it helps to understand the Japanese term from which it took its name. It was coined in the Edo Period, a time when leather workers and others in “unclean” professions were ostracised and forced to live in small settlements apart from the general population. They were referred to as burakumin, and while these communities have long since disappeared, the word still retains some of its old meaning. By choosing to name their brand Blackmeans, an English transliteration of burakumin, Messrs Yujiro Komatsu, Masatomo Ariga and Takatomo Ariga were embracing their own pariah status as punk rockers while also paying homage to the centuries-old traditions of Japanese leathercraft.

For the full Blackmeans experience, you really need to visit the brand’s custom studio in Tokyo, where jackets are hand-embellished with so many studs, buckles and patches that you can barely see the leather any more. Having said that, though, even its more straightforward pieces – shirts, jackets and denim released under the wider Blackmeans brand – are still crafted with the same expertise and artisanal ethos.