THE JOURNAL

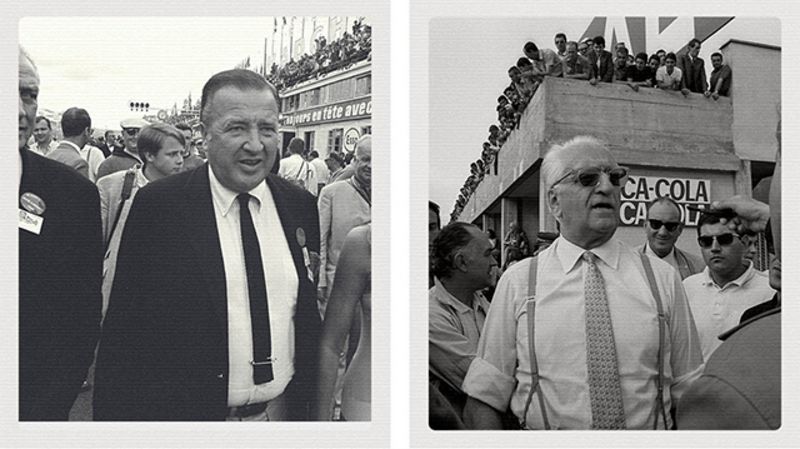

Left: Mr Henry Ford II at the 24 Hours of Le Mans race, France, 1966 Photo courtesy The Ford Motor Company; Right: Mr Enzo Ferrari at the Monza race, Italy, 1967 Photo Rainer W Schlegelmilch/ Getty Images

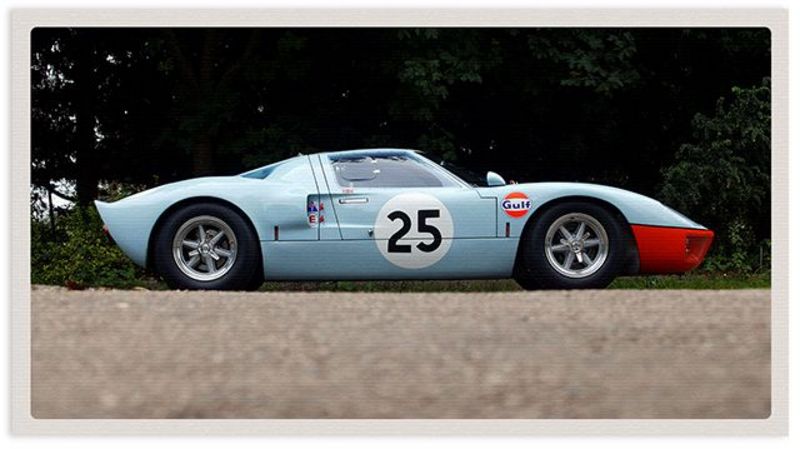

Revenge has never looked as good as the Ford GT40. Standing just 40-inches tall, its roar is the sound of Detroit in its 1960s prime: thunderous, swaggering. Instead of burning fuel you expect to smell pomade, leather and cigars. Old-school corporate America in its virile pomp. To call it a mere race car is like calling the Stealth Bomber just another plane. Sure, one drives and the other flies. But they were built with a grander purpose in mind: to prove that America might be slow to anger, but once goaded, will invest all the money, guts and talent it takes to win.

In 1964, Mr Henry Ford II, known as “Deuce” or “Hank the Deuce ”, the grandson of Ford’s founder, decided he wanted a car capable of winning on the race tracks of Europe. In particular, he wanted to win the greatest race of all, the 24 Hours of Le Mans. He wanted to snatch it from Mr Enzo Ferrari, whose cars had won every year since 1960. Mr Ferrari, he felt, had cheated him and Deuce wanted payback. And what Deuce wanted, he tended to get.

Mr Ford was as bold and expansive as America’s booming post-war economy. A millionaire hundreds of times over at birth, he could have spent his life cowering inside his Grosse Pointe mansion, watching interest compound his fortune. But he had seen his father, Mr Edsel Ford, crumple in the shadow of his grandfather. He understood that in the car business, aggression and risk taking were the only ways to win. It helped that he had the burly presence of a Detroit Lions linebacker and that his words hit like spine-crunching tackles.

The Ford GT40 photographed in 2008 Photo Magic Car Pics/ Rex Features

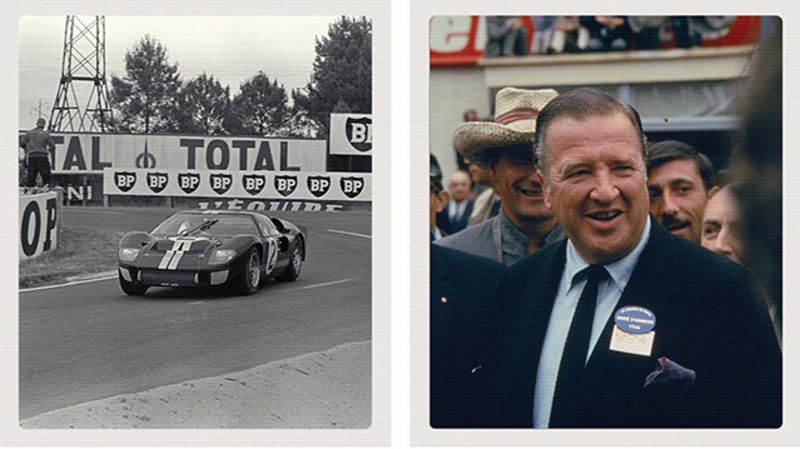

Left: Mr Bruce McLaren in the winning GT40 at the Mulsanne hairpin, 24 Hours of Le Mans race, France, 1966 Photo courtesy The Ford Motor Company; Right; Mr Ford II at the 24 Hours of Le Mans race, France, 1966 Photo courtesy The Ford Motor Company

Mr Ford understood that in the car business, aggression and risk taking were the only ways to win

Ford’s car plants were some of the biggest in the world, churning out thousands of automobiles a week for the burgeoning American and European middle classes. Mr Ford and his executives occupied a vast office building in Detroit known as the Glass House, and travelled the world by private plane, helicopters and Lincoln limousines.

Mr Ferrari had grown up very differently. Born in the foggy, agricultural lowlands of Italy’s Emilia-Romagna, he had little formal education. He was a decent, not spectacular, race driver. After several years running the racing operations for Alfa Romeo, he launched his own marque shortly after WWII.

Mr Ferrari had a single workshop in his home town of Modena, where his craftsmen built their cars by hand, everything from the engines to the door handles, cut, drilled and assembled to exacting standards. His office was next door to the workshop; and his apartment above. He ate lunch every day at a restaurant across the street, Cavallino, which eventually he owned. He rarely left Modena and never Italy. Yet the race cars which emerged from this modest set-up quickly came to dominate European racing. Sleek and nimble, they emitted a strange contralto whinny as they flew by, blurs of racing red.

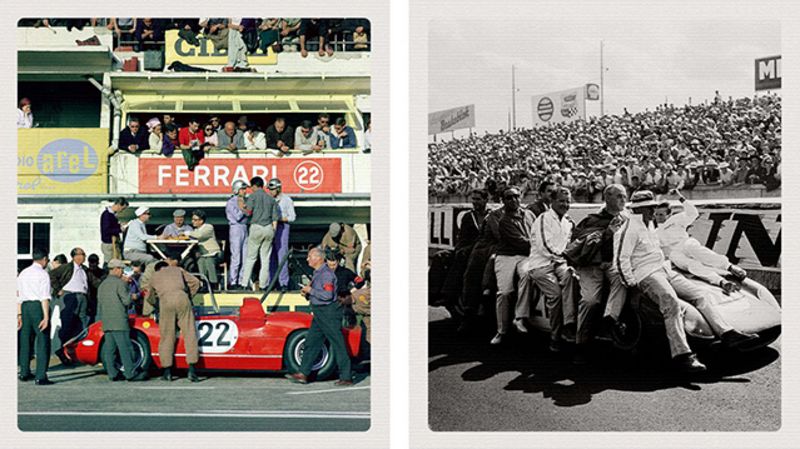

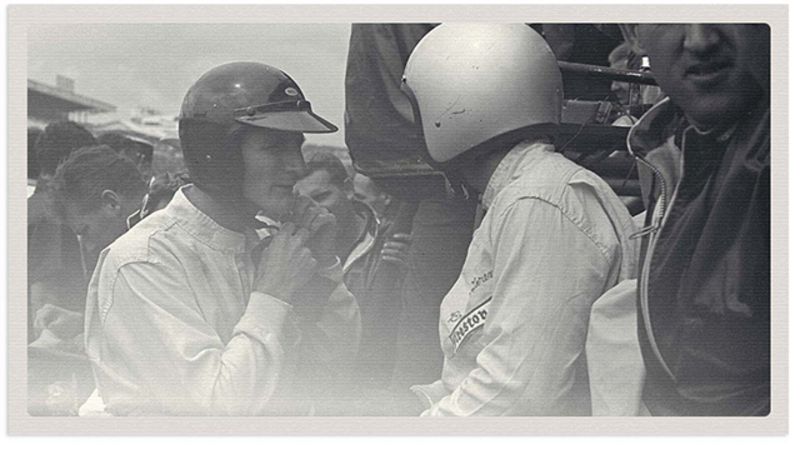

Left: Drivers Messrs Giancarlo Baghetti and Umberto Maglioli confer with chief engineer Mr Mauro Forghieri at the 24 Hours of Le Mans race, France, 1964 Photo Klemantaski Collection/ Getty Images; Right: The winning Ferrari team, 24 Hours of Le Mans race, France, 1965 Photo Rainer W Schlegelmilch/ Getty Images

Mr Ford vowed to his executives: "We’ll beat his ass"

Despite the gulf between their companies and lifestyles, Messrs Ford and Ferrari had certain similarities. They were both tyrannical and obsessive about their cars. They did not flinch at the danger of motor sport, or retreat when their drivers were killed, which happened with appalling regularity. By the force of their own personalities, they could channel the wild ambitions of their employees, their headstrong team managers, pernickety engineers and highly strung drivers, towards their own imperious goals. It was perhaps inevitable that these two automotive titans would clash.

In 1963, Ford received word that Ferrari was looking for a buyer. Ford had already decided that racing would be an excellent way to market its cars. Mr Lee Iacocca, then one of Mr Ford’s top executives, believed that buying Ferrari would lend Ford a reputation for speed and European sex appeal which would help sell cars. Mr Ford was enthusiastic. He had long been a fan of Mr Ferrari’s cars. In 1952, Mr Ferrari had given him a black 212 Barchetta, to which Mr Ford had added Firestone whitewall racing tires.

A group of Mr Ford’s executives travelled to Modena where they were astounded by the cleanliness and craftsmanship of Mr Ferrari’s operations. But as they negotiated the sale, Mr Ferrari balked. He could not, he said, cede control of his racing team. It turned out that Ford had been played.

Mr Ferrari had been under pressure. The popular German driver Mr Wolfgang von Trips had died in a Ferrari at Monza in late 1961 in a crash that killed 14 spectators. Mr Ferrari’s staff were unsettled by a government investigation and resigned in droves. The wife of one of Mr Ferrari’s drivers called him “an assassin” for paying so little heed to his drivers’ safety. The company was bleeding money. By letting news of Ford’s interest leak out, Mr Ferrari reversed the bad publicity. Suddenly, he was an Italian industrial champion, one who had to be protected from American clutches.

Mr Ford was furious and decided to challenge Ferrari head on. He would regain the reputation for engineering and technological innovation lost at the company since his grandfather’s time. And he would do so at Mr Ferrari’s expense. He vowed to his executives: “We’ll beat his ass.”

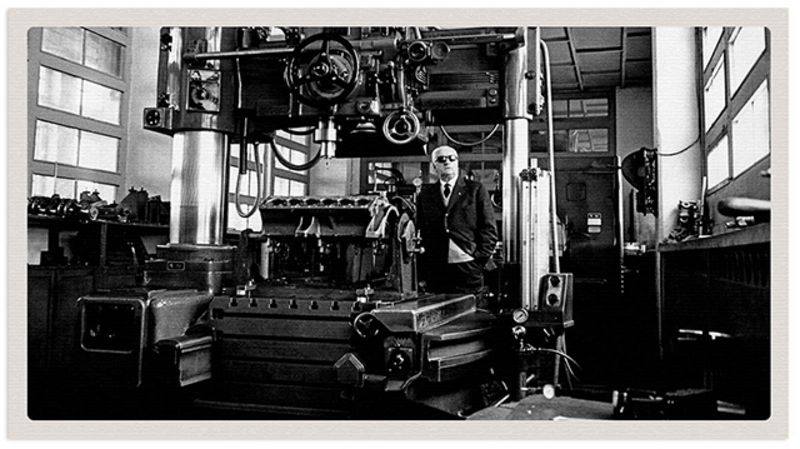

Mr Ferrari posing beside machinery in his factory in Mantova, Italy, 1966 Photo Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images

Mr Ford sent out a card to the heads of all his divisions. Underneath a sticker of the Le Mans race, it read, "You better win"

The finest engineers were assembled and set to work under the guidance of Mr Carroll Shelby, a tall, charming Texan who had won Le Mans in 1959 driving an Aston Martin. For all the money and expertise invested in the project, it took time for the GT40 to be competitive. Under Mr Shelby’s predecessor, Mr John Wyer, at its first Le Mans in 1964, all of Ford’s three GT40s retired with less than half the race gone. One burst into flames and the two others succumbed to their faulty Italian transmissions. Mr Ferrari’s cars took five of the top six places, including the win. Mr Shelby took the helm after the 1964 Nassau race.

However, 1965 was no better. Seven hours into the race, the GT40s were out, smouldering in the pits, victims of overheating and mechanical failure. Investment totalling $6m ($45m today) had produced nothing. Once again, a Ferrari won.

In late summer 1965, Mr Ford sent out a card to the heads of all his divisions. Underneath a sticker of the Le Mans race, it read, “You better win”. Mr Ken Miles, a British driver with a passion for wine, gardening and gruelling runs near his home in the Hollywood Hills, had become the GT40’s lead driver. He had a near mystical feel for the car. But he could do nothing for the veteran American driver, Mr Walt Hansgen, whose GT40 cartwheeled off the Le Mans track during testing. Mr Hansgen died five days later in hospital. Accidents were far more common in motor sport at the time, but Ford’s accelerated development programme had its engineers scrambling to learn in months what Ferrari had learnt over years.

Messrs Ken Miles and McLaren in the Ford pit stop, 24 Hours of Le Mans race, France, 1966 Photo courtesy The Ford Motor Company

The Ford team arrived at Le Mans that year with all the subtlety of an invading army. More than 100 men, planes groaning under the weight of cars, engines and equipment. Mr Ford arrived by helicopter, accompanied by his recently acquired second wife, a glamorous Italian, Ms Cristina Vettore Austin. As Honorary Grand Marshal, he dropped the flag to start the race at 4pm on 18 June. The Fords shot into the lead, faster by far than the competition. There were none of the mistakes of previous years. The pit stops were flawless. The GT40s slashed through the night and the rain. When Mr Ford returned at 11am the next morning, he was told that Fords were running first, second, third. That was how they finished. The Ferraris were nowhere.

The GT40 would repeat the feat in each of the next three years. Only seven road versions of the GT40 were ever built, and are prized by collectors. Their sporting legacy, however, infused Ford’s DNA for decades to come, notably in cars such as the Mustang. In 2005, the company briefly produced a road GT in honour of the GT40. But whatever money had been spent to develop the GT40 was more than made up for as Ford’s sales in America and Europe boomed. Mr Ferrari soon turned his attention to Formula One. He never won Le Mans again.