THE JOURNAL

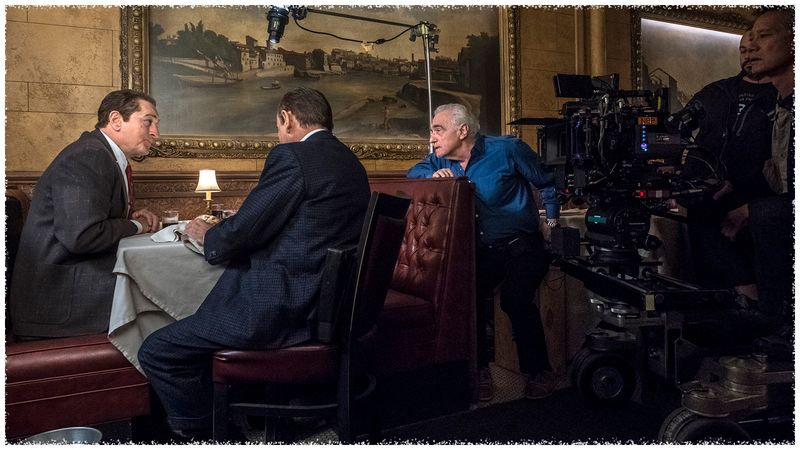

Messrs Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Martin Scorsese on set of The Irishman. Photograph by Mr Niko Tavernise/Netflix

Mr Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, released on Netflix UK yesterday, has been lauded as a career high to compare with Raging Bull, Taxi Driver and Goodfellas. At 77, Mr Scorsese’s recent output has been rich and unfettered, from hyperactive corporate satires (The Wolf Of Wall Street) to an austere tale of 17th-century Jesuit priests in Japan (Silence).

A new classic from an old master is always particularly satisfying. In his book On Late Style, Palestinian academic Professor Edward Said noted shared qualities and contradictions in the final works of artists including Mr Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Mr Ludwig Van Beethoven and Mr Thomas Mann. Cold control and quasi-religious stillness are often at odds with unfulfilled desires. Some are more serenely accepting of impending death than others.

The brilliance of The Irishman has inspired us to reflect on cinema’s other late masterworks. A Hidden Life, the new film from Mr Terrence Malick, 75, bolsters his characteristic lyricism with an anti-fascist political relevance. Mr Paul Schrader, 73, who co-wrote Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, found a stark ethereal power in his film First Reformed, in which Mr Ethan Hawke mesmerised as a disenchanted priest. Patterns emerge. The direction is both more compressed and spiritually free. Performances have a virtuosic restraint. But there are also individual contradictions that offer intriguing observations on the director’s own sense of mortality. Here are our top five.

Mr Luis Buñuel, 72

The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie (1972)

Mr Paul Frankeur, Mr Claude Pieplu, Ms Stéphane Audran, Mr Fernando Rey, Ms Bulle Ogier, Mr Julien Bertheau, Ms Delphine Seyrig and Jean-Pierre Cassel in The Discreet Charm of The Bourgeoisie. Photograph by Landmark Media

Mr Luis Buñuel, Spanish doyen of surrealist cinema, combined elements of his earlier career – the free-associative shocks of Un Chien Andalou (1929), the subversiveness of Viridiana (1961), the sexual dualities of Belle De Jour (1967) – for perhaps his funniest, most accessible film. Loosely about two middle-class French couples, whose attempts to have a dinner party are thwarted by increasingly extreme interruptions, The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie mixes elements of bedroom farce, high arthouse and outlandish satire that mocks, among other things, the church, the army, dictatorships and terrorism. A mad, mischievous joy.

Mr Stanley Kubrick, 70

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

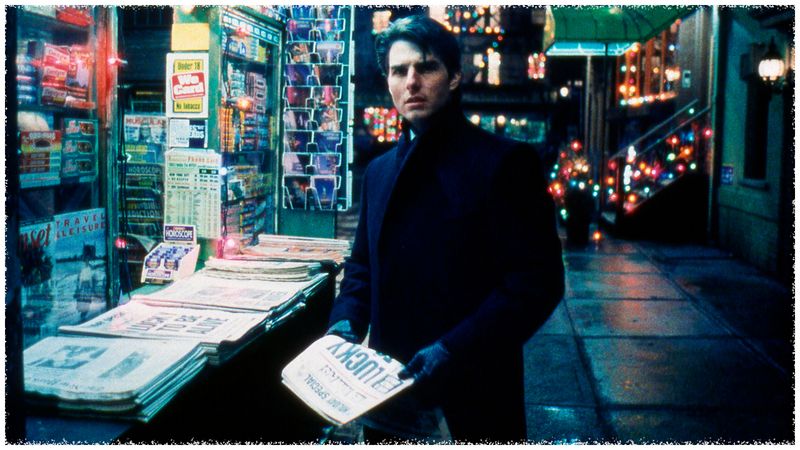

Mr Tom Cruise in Eyes Wide Shut. Photograph by Collection Christophel/Alamy

Mr Jon Ronson’s excellent documentary Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes shows the new levels of obsession to which the exacting Mr Kubrick went to to make his final film. Twelve years after Full Metal Jacket and based on a 1926 Austrian psychosexual novella, Eyes Wide Shut holds the Guinness World Record for the longest continuous film shoot, at 400 days. Real-life couple Mr Tom Cruise and Ms Nicole Kidman play a wealthy New York husband and wife tempted to cheat on each other. It’s a mythical, nightmarish enigma, with Mr Kubrick’s characteristic clue-dense frames, such as the haunting tracking shot of a masked orgy.

Mr Robert Altman, 76

Gosford Park (2001)

Mr Laurence Fox, Mr Jeremy Northam, Mr Charles Dance, Ms Kristin Scott Thomas, Mr James Wilby and Ms Claudie Blakley in Gosford Park. Photograph by Sportsphoto/Allstar

A New Hollywood master of the sprawling ensemble, Mr Robert Altman immaculately transposed the jealous hierarchies of country music (Nashville) and 1900s Los Angeles (The Player) to a 1930s English country estate for Gosford Park. The characterisation is as nuanced as ever, particularly Dame Helen Mirren’s housekeeper (her finest film performance ever?) and Sir Alan Bates’ tortured butler. Inspired by Mr Jean Renoir’s The Rules Of The Game, the cinematography is as stately as the architecture (that opening shot with the umbrella…). Gosford Park was Lord Julian Fellowes’ darker-hued, Oscar-winning blueprint for global phenomenon Downton Abbey.

Mr Sidney Lumet, 83

Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007)

Messrs Ethan Hawke and Philip Seymour Hoffman in Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead. Photograph by Sportsphoto/Allstar.

A revered titan ever since his 1958 film 12 Angry Men, Mr Sidney Lumet found a new fury with his final movie. Two brothers, played by Mr Philip Seymour Hoffman and Mr Ethan Hawke, plot to pay off their debts by robbing their parents’ jewellery shop, with catastrophic results. It’s a rivetingly dark exploration of family betrayal, a tonal prelude to Fargo and Succession and Mr Albert Finney gives a late masterclass of his own as the beleaguered dad.

Mr James Ivory, 91

Call Me By Your Name (2017)

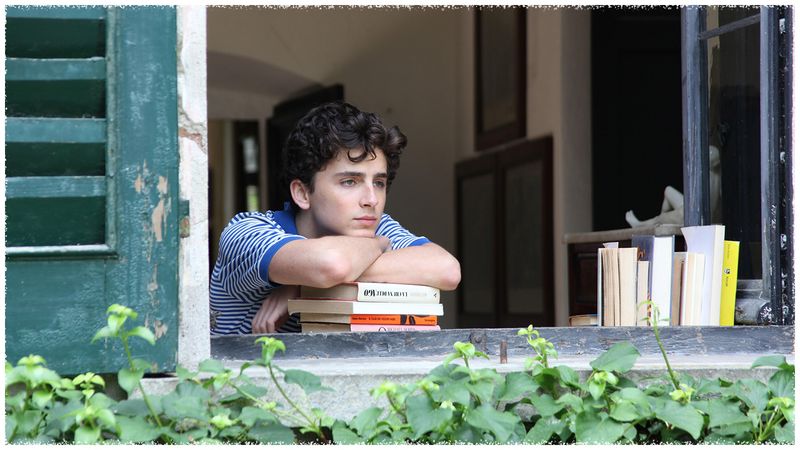

Mr Timothée Chalamet in Call Me By Your Name. Photograph by Photo 12/Alamy

Call Me By Your Name is one of the cinematic delights of the decade, a gorgeous elegy to the summer idyll of first love. And while the direction and performances were rightly acclaimed, Mr James Ivory’s script was particularly revolutionary. When he won the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay, Mr Ivory was the oldest winner in that category. An expert in emotional restraint (like Sir Anthony Hopkins’ reluctance to show Ms Emma Thompson the book in The Remains Of The Day), Mr Ivory’s adaptation of Mr André Aciman’s novel is a perfect mix of classical and modern, ancient statues at ease with Mr Sufjan Stevens. The script is full of unusual wisdom and empty of clichés. It’s much fresher, for instance, that Elio’s parents are liberal. The dad’s monologue on heartbreak is the film’s glorious zenith.