THE JOURNAL

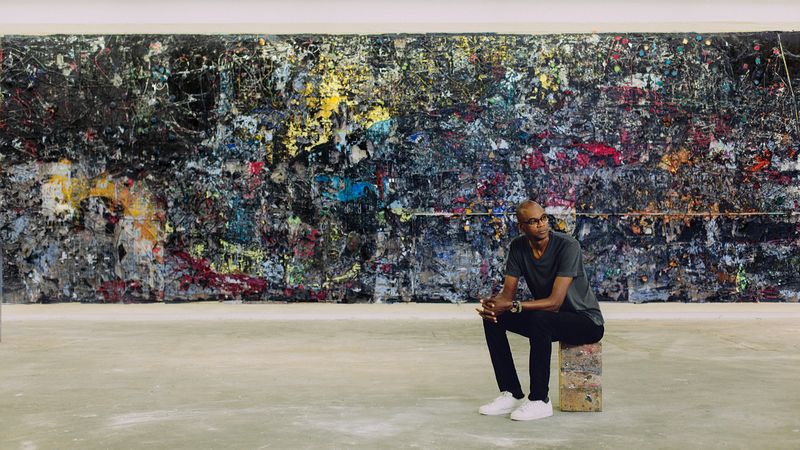

“Cerberus”, 2018, mixed media on canvas by Mr Mark Bradford

In this age of frantic alarm over borders, Hades’ old hound Cerberus – the wild, three-headed beast that entraps the doomed in the underworld and spares the innocent – makes for a screamingly appropriate symbol. And Cerberus is the gathering point around which the Angeleno artist Mr Mark Bradford has built the body of work that he will show during Frieze London next month. “It was one of my childhood obsessions,” says Mr Bradford from his studio in Venice, California. “Cerberus, it haunted my dreams.”

According to the artist, these new pieces, executed in Mr Bradford’s signature style – dense layers of paper applied to a stretched canvas then carved up – are largely about containment. Or else: “This idea that a destabilised environment and destabilised political world makes for unease no matter where you are in it. And I thought to do a body of work about when things break down.”

Breakdowns – as well as creativity even in the midst of that turmoil – have been some of the only constants for Mr Bradford. Born and raised in a boarding house in Los Angeles, at the age of 11 he moved with his mother to Santa Monica, where he was bullied and ostracised. He sets the scene: “Listen, I’m just a little kid, like, picking a flower and putting it in my hair. I’m just doing my thing, but I become very aware very quickly that there’s a pack of people saying that that’s not appropriate. ‘And we’re going to physically do something to you.’ Now there’s a crisis. It’s not coming from me. But there’s an imminent threat. So, you figure out creative ways to navigate that schoolyard to get around that threat.”

As he grew older, he found an outlet in LA’s club scene during the 1980s. “I’m 17 years old and I’m looking in the mirror like, ‘Woo,’” he says. “I thought I had a nice little smile. I’m getting ready to get out there. Free love! Do my thing, you know? And then there’s this thing called Aids. They didn’t even have a name for it yet. The government doesn’t even want to say it exists. All my friends just started dying. I mean it was a... How can you be young and old at the same time? How do you bury 21-year-olds? But that’s what was happening. Again, another threat.”

Throughout his twenties and thirties, in between stints working in his mother’s hair salon, Mr Bradford spent much of his time travelling alone through Europe. But it was in the salon that he learned to be the storyteller he is today. “Please,” he says, “that’s all I did.” Talk, he means. “People now say that I speak very clearly. It’s because if I didn’t, the women in the salon would force me to retell it. ‘Say it again, Bradford. Speak up. What club did you go to?’ And I was like, all right, I better be entertaining, too. You have the floor, you gotta make it funny.”

As good as he is with words, he communicates most honestly through his art. “The work is everything,” he says. “[Communication] is a slow, laborious process and we are such tricky animals. We have all kinds of filters to avoid the thing. Don’t think for one minute we don’t. And so, when I’m an artist, I’m super aware of the trickery, but my hand is more honest, actually. When I get out the materials, the sander, and the colours are all dripping around me, that’s where I want to be.”

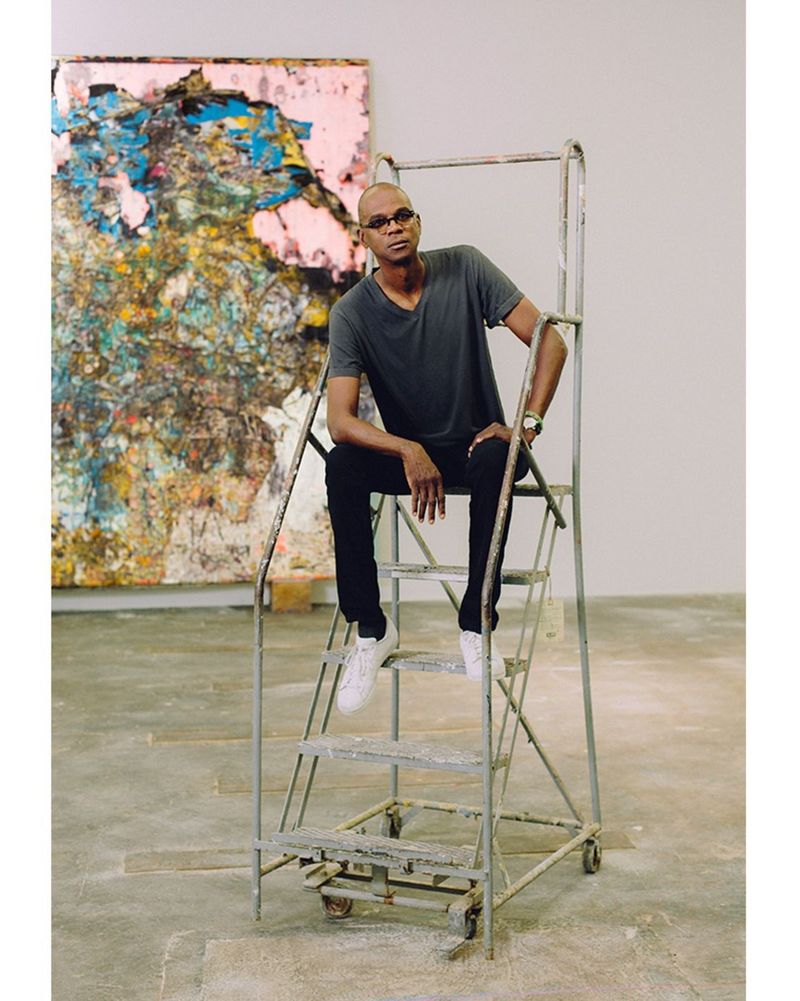

“Gatekeeper”, 2019, mixed media on canvas by Mr Mark Bradford

His expressive application of both sander and colour has made Mr Bradford something of a rock star in the art world. Since he sold his first painting at the age of 40 (a little over 15 years ago) for $3,500, he’s become borderline legendary. In 2017, he was chosen as the representative of the US at the Venice Biennale and, in the spring of this year, he was profiled by Mr Anderson Cooper on 60 Minutes. His oeuvre is shown constantly around the world and collected by the most august museums. But, he says, he is still that little kid putting a flower behind his ear – eluding his minders in Shanghai recently, for example, to go and snoop around the city on his own.

As his work has amplified his presence in the industry, Mr Bradford has set about amplifying the presence of art in his community. An exhibition space and education centre in Leimert Park, Los Angeles, called Art + Practice provides specialised training for children in foster care. And while he was in Venice creating his exhibition for the Biennale, Mr Bradford partnered with a local social co-op and nonprofit that helps reintegrate formerly incarcerated men and women by providing them with employment opportunities.

“You know what,” he says, “I had big ideas when I was six, you know, but I just had to be given the land.” He means land metaphorically – weight, power, money, stake. “I knew exactly what to do with the land when I got some. I always wanted to have a foundation to give people access to ideas. I always wanted to share knowledge.” As an autodidact himself, Mr Bradford thrills at the idea of providing young artists with a place to develop possible outlets for their creativity, and thus possible pathways towards better futures.

From left: “Frostbite”, 2019, mixed media on canvas; “Gatekeeper”, 2019, mixed media on canvas; “Cerberus”, 2018, mixed media on canvas, all by Mr Mark Bradford

This is the dynamic appeal of Mr Bradford – his work is at once expansive and deeply personal. He describes his process as a kind of burrowing into the deepest chambers of himself. “I’m kind of hermetic with it,” he says. “The ropes and the twine and the power washers – the making – gives me a deeper guide post into my psychology and emotional condition than the materials.” But, he says, “History and mythology and social dynamics remain the starting points.”

**Mark Bradford: Los Angeles is at the Long Museum, Shanghai, until 13 October. **

Cerberus is at Hauser & Wirth, London, from 2 October until 21 December.