THE JOURNAL

Ordos Museum, 2005–2011, Ordos, China. Photograph by Mr Iwan Baan. Courtesy of Phaidon

How Beijing-born Mr Ma Yansong is changing the world one building at a time. Here are three of his best – Absolute Towers, Harbin Opera House and Ordos Museum.

Beijing-born architect Mr Ma Yansong is one of the most intriguing talents of his generation, known for the startling, sinuous and organic-looking buildings he masterminds via his architectural practice, the somewhat aptly named MAD. A protégé of the late architectural pioneer Ms Zaha Hadid, who he met while completing his thesis at Yale, Mr Yansong is clearly influenced by his forebear’s swooping, futuristic forms – see, for example MAD’s branch-like China Wood Sculpture Museum in Harbin, China.

However, where Ms Hadid’s work has a certain hyper-modernist rigour, MAD’s buildings are startlingly wide-ranging in their influences and forms. Though they often refer to the natural world, as in the leafy “Urban Forest” tower project in Chongqing, or the globular “Hutong Bubbles” in Beijing, no two buildings really look alike, and each new project comes as something of a surprise.

As well as being highly regarded in its home country, MAD is one of the first contemporary Chinese practices to achieve widespread acclaim (and win competitions) in the West, a fact that’s reflected in this month’s publication of MAD Works, a major monograph work by Phaidon.

The book is the first major overview of MAD’s many architectural projects, arranged thematically and exploring the practice’s ideas and working methods as well as delving into the final designs. Scroll down to discover a few of MR PORTER’s favourites.

Absolute World towers

Absolute Towers, 2006–2012, Mississauga, Canada. Photograph by Mr Tom Arban. Courtesy of Phaidon

Mississauga, Canada

MAD’s first realised project was the Absolute World towers in Mississauga, Canada, completed in 2012. Nicknamed “Marilyn Monroe” for their curvaceous forms, the buildings were designed to shatter the general association of skyscrapers with high capitalism, money and power by virtue of their sheer organic weirdness. The undulating, precarious-looking forms of each tower are less Wall Street, more 23rd-century utopian settlement.

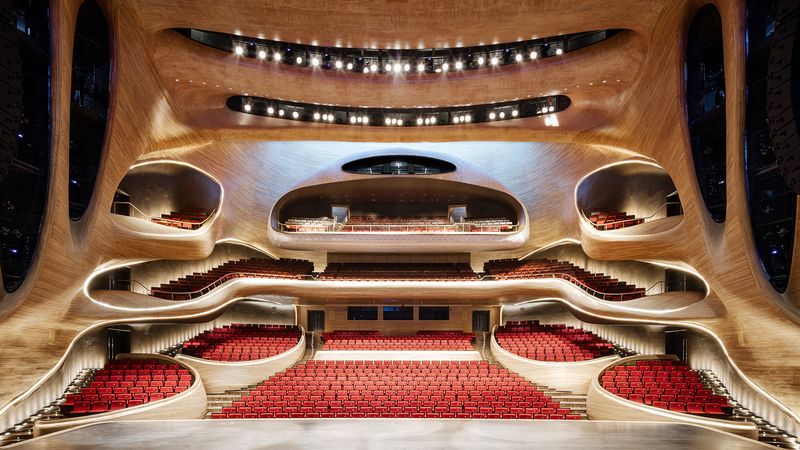

the Harbin Opera House and Cultural Centre

Harbin Opera House, 2009–2015, Harbin, China. Photograph by Mr Adam Mørk. Courtesy of Phaidon

Harbin, China

One of MAD’s most recently completed projects, the Harbin Opera House and Cultural Centre, has been open since 2015. Its design reflects the topography of the surrounding area – composed mostly of wetlands – with an exterior shell that looks like it has been shaped organically by wind and water. The interior, however is no less impressive, as demonstrated by the above image of the auditorium, which is sculpted in manchurian ash for both aesthetic and acoustic purposes.

the Ordos Art & City Museum

Ordos Museum, 2005–2011, Ordos, China. Photograph by Mr Iwan Baan. Courtesy of Phaidon

Gobi Desert, Inner Mongolia

In the Western media, there are many conflicting views about Ordos, the new city that, since 2008, the Chinese government has been building in the Gobi Desert, Inner Mongolia. Some have called the project a failure, citing the conspicuous lack of people to have taken up residence in its grandiose structures. More recently, Forbes defended the project, arguing, quite rightly, that any major development such as this has a gestation period. In any case, everyone can agree that MAD’s design for the Ordos Art & City Museum is at least an architectural success, with its blob-like form both echoing the landscape that surrounds it and protecting it from the area’s frequent sandstorms.