THE JOURNAL

Mr Harrison Ford in Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981). Photograph by The Ronald Grant Archive

Film-making is a risky business. Introducing the movies that have set our pulses racing.

The urge to watch acts of daredevilry is with us from the start. Which of us didn’t spend an idle moment at school transfixed as a classmate leapt off an impossibly high wall into a jungle of nettles to retrieve a football, or repurposed a Bunsen burner as a flame-thrower? Back then, the result was a trip to the nurse and detentions all round. But the hunger to see someone else massively imperil their own physical welfare never goes away.

For all the revolution of computer effects, our own desires have barely changed since the moving picture audiences of 1923 gasped in awe as silent comedian Mr Harold Lloyd hung from a clock on top of a skyscraper in Safety Last! More recently, a legion of studio executives with crumpled insurance paperwork gazed in terror as Mr Tom Cruise clung to the summit of the world’s tallest building, Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, in Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol.

Or take The Revenant from earlier this year – on the one hand a rich allegory for American expansionism; on the other a chance to see Mr Leonardo DiCaprio get on the wrong side of a bear as the prelude to a bloody variant on a Tough Mudder assault course. Danger: it’s the stuff of movie life. Sometimes it comes in a film about what are clearly dicey activities to begin with: scaling mountains or walking highwires. At other points, a stunt from out of nowhere is enough to leave us boggling at the risks people will take for our entertainment. Which is where, of course, we come in. MR PORTER presents eight timeless, occasionally ludicrous moments of danger in movie history. We’ll see you in A&E.

Senna (2010)

Photograph by Allstar Picture Library

In another life, Mr Ayrton Senna might have been a brilliant surgeon or a crusading politician. The son of a wealthy Brazilian family, blessed with good looks and limitless charisma, he decided to drive Formula 1 cars, with more ferocious precision than the sport had ever seen. You glimpse the shape of the man in Senna, the exhilarating, ultimately heartbreaking documentary from British director Mr Asif Kapadia. It’s an artful mash-up of archive film: old go-kart races, TV interviews, at least one bad-tempered meeting between off-duty drivers. But the real rush comes with the footage from Mr Senna’s in-car camera. The results could send the heart of a Buddhist monk into palpitations, as Mr Senna and his hulking dart of metal duel on the blurred tarmacs of Silverstone and Monaco. By the time of the grandstand home victory at the Brazilian Grand Prix, if you’re not out of your seat and cheering, you may need more than a movie to help you.

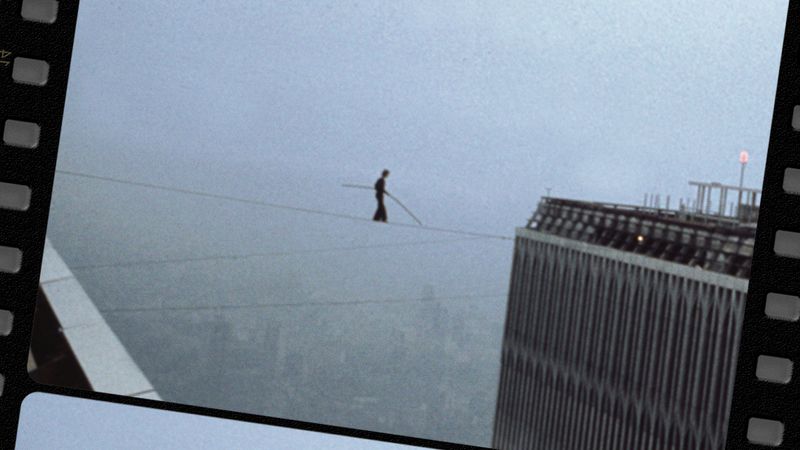

Man On Wire (2008)

Photograph by Mr Jean Louis Blondeau/Eyevine

For those of us whose physical coordination is bad enough to make getting out of the shower a risk, there is Man On Wire, a glorious documentary about the scarcely plausible exploits of Mr Philippe Petit. Back in the hairy wastelands of 1974, tightrope walker Mr Petit was a trained circus performer, but one it would be unwise to file alongside any old mime or juggler. With a unique taste for danger, he was about to carry out perhaps the most audacious real-life stunt in history. On a hazy August morning, Mr Petit slung a wire between the Twin Towers of New York’s World Trade Center, stepped onto it – and spent the next three-quarters of an hour strolling 1,350ft above the city, stopping only for the occasional jaunty pirouette. The actual walk was the culmination of a six-year plan and a whole bundle of mischief, not least having broken into the World Trade Center in the first place. The devil.

Police Story (1985)

Photograph by Collection Christophel/Photoshot

We could hardly give you this piece without mentioning Mr Jackie Chan, the eternally chipper Hong Kong martial artist whose stunts suggest a happy but profound indifference to his own wellbeing. And of all the movies he’s filled with his deranged antics, none were so perilous as Police Story. On the face of it a standard-issue crime thriller, its action sequences had the feel of a series of playground dares played out by one beaming adult. None more so than the reckless moment in which finding himself stranded at the top of a four-storey shopping mall, our man elects to descend a pole wrapped in electric Christmas lights that ran the full height of the building. The pole was real, as were the lights, as were the injuries and burns sustained by Mr Chan en route, inevitably, to smashing through the roof of a shop below. He was still smiling (we assume).

Drive (2011)

Photograph by REX Shutterstock

They call it a J-turn. That’s the act of doing 50mph in reverse for a length of road that is frankly just ridiculous, before spinning the car 180 degrees and speeding away in the same direction, only this time going forward. It was just one of the many tricks in the professional toolkit of the anonymous stunt driver played by Mr Ryan Gosling in the neon-lit LA-rama of Drive. It’s worth noting that Mr Gosling executed most of them while keeping a toothpick in situ. It might also be worth noting that most of the real stunts were executed with the help of a technical rig in which Mr Gosling really was at the wheel while filming, but with an actual stunt driver controlling the car from behind him in a pod called, mystifyingly, “the Biscuit”.

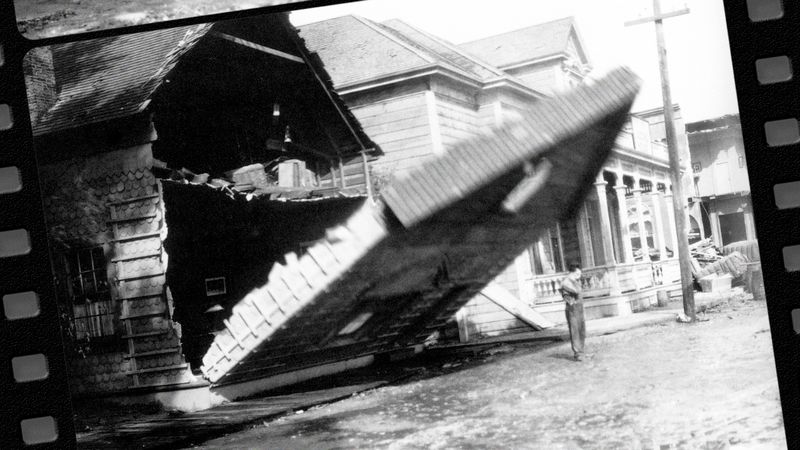

Steamboat Bill Jr (1928)

Photograph by The Ronald Grant Archive

In the early days of movies, the only thing the public loved as much as a stunt was a belly laugh. With Mr Buster Keaton, they got both: a great silent comedian who was also a serial mistreater of his own body. Of the countless insanely hazardous stunts he devised for himself, the most infamous came in Steamboat Bill Jr, the story of a young fop coming of age that ends with a cyclone hitting town. As the winds rage, our hero blearily looks out towards the camera. What he doesn’t know is that, behind him, an entire housefront is toppling forward. For a moment you stare in horror. Thankfully, there’s a single open window frame in the facade that is just big enough to fit over him. Had he been standing six inches to his right, that would have been that – and in real life, too, the CGI of 1928 still lacking a certain refinement.

Point Break (1991/2015)

Photograph by The Moviestore Collection

And here we pause to cheat just slightly, slipping two films into one slot. The original Point Break was, let’s say, a more dramatically satisfying film than its 2015 remake. It also features its own moments of crazed daring, notably when Mr Patrick Swayze insisted on shooting the film’s indelible skydiving scene for real (sensibly, co-star Mr Keanu Reeves did not). But in one respect the remake trounced the original – in the brain-addling scale of its action set-pieces. Of course, as tradition dictated, there was surfing, filmed here in the Jaws surf break in Maui. But having recruited a gaggle of stuntmen versed in extreme sports, the film-makers then produced less a movie than a showreel for their skillsets. And so they snowboarded, they rock-climbed and then, in one of the most authentically queasy sights in cinema, four of them and a cameraman flew solo through a high Alpine pass in bat-like “wingsuits.” It may give you vertigo to watch. This is probably the point. Elsewhere in this issue of The Journal, we couldn’t resist interviewing one such human bat.

Touching The Void (2003)

Photograph by Allstar Picture Library

You are high in the majestic Peruvian Andes, 20,000ft up on a brutal peak never before conquered. There is a fleeting moment of triumph – and then a breakfast buffet of disasters, at the end of which your climbing partner is left dangling from a cliff, in the middle of a whiteout snowstorm, with a broken leg and just a length of rope connecting you. And this is only the start of Touching The Void, a mighty documentary about British climbers Messrs Joe Simpson and Simon Yates. Upon it hangs, as well as a thrilling tale, a momentous moral dilemma. In the hands of director Mr Kevin Macdonald, the film manages to be at once a glorious salute to the staunch spirit of mountaineers and a dire warning to never climb anything in flip-flops.

Raiders Of The Lost Ark (1981)

Photograph by Collection Christophel/Photoshot

Clearly, much that went on in the big-screen debut of adventurer Indiana Jones was ill-advised from a health and safety perspective. (We refer you also to the opening scene with its theft of an ancient artefact from a booby-trapped temple.) But peak risk arrived in the moment Mr Harrison Ford’s intrepid archaeologist found himself exchanging views with a group of Nazis as they drove a truck at speed down a desert highway. Needing a quick getaway, Jones slipped under the chassis from the bonnet – then hauled himself down the moving vehicle as if it was a set of monkey bars to emerge at the bumper, attaching himself with a rope to be dragged along in the dust. The scene was executed with a cheerful low-fi realism: the wheels of the truck had been raised and a small trench dug to give the stuntman a precious couple of extra inches in which to almost kill himself for the passing glee of a generation of ungrateful 1980s kids.