THE JOURNAL

A new book celebrates the field of design.

The word “brutalist” is usually used to describe the austere, concrete social architecture of Britain in the mid-20th century. As we’ve remarked previously on The Daily, it’s become a bit of a trendy term in the current era. In particular, 2016 saw a slew of books dedicated to the topic, from Mr Barnabas Calder’s Raw Concrete (William Heinemann) and Mr Peter Chadwick’s This Brutal World (Phaidon) to two books called Brutal London (one a novelty book of build-your-own brutalist buildings, the other a walking guide to Brutalist buildings in London, which we reviewed here). In 2017, there’s more in the offing, including architect Mr Simon Henley’s thoughtful Redefining Brutalism (RIBA) and Finding Brutalism: A Photographic Survey Of Post-War British Architecture which is published by Park Books this November.

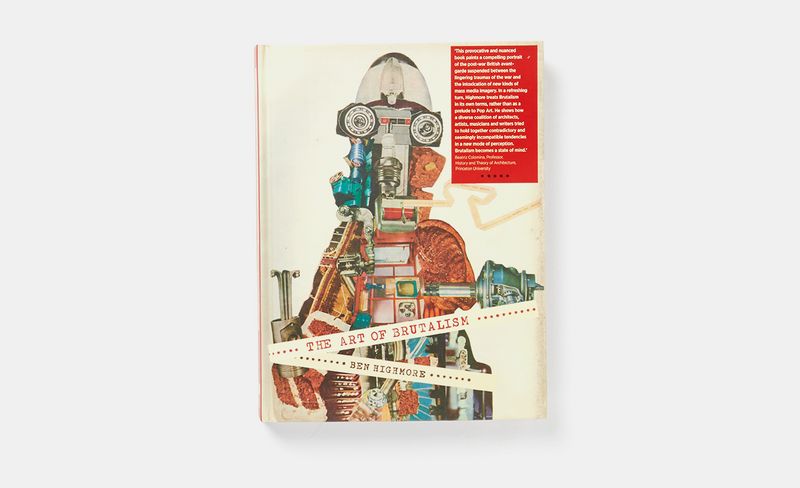

So, the architecture angle is pretty much covered, then. But that’s what makes Mr Ben Highmore’s new book The Art Of Brutalism something of a refreshing offering within this niche field. Focusing on the works of artists such as Messrs Eduardo Paolozzi, Nigel Henderson, William Turnbull and Richard Hamilton, Ms Magda Cordell, and husband and wife architects Mr Peter and Ms Alison Smithson – early members of the so-called “Independent Group”, which met at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) between 1952 and 1955 – Mr Highmore makes the case that, rather being a mere prelude to the onset of pop art in the 1960s, brutalism was an artistic movement in its own right. According to Mr Highmore, though brutalist art – like pop art – brought the imagery and ephemera of mass media into the realm of fine art, it was far less reverent to such subject matter, more symptomatic of a mechanised post-war Britain that had been ruined, and was being rebuilt.

“If there is one overarching mood that characterises this period for the brutalist milieu, it could be described as haunted-optimism”

Mr Highmore expounds his thesis by concentrating on a handful of key incidents within the history of Brutalism and the Independent Group. There’s the 1953 exhibition _Parallel Of Life And Ar_t, mounted by the Smithsons with Messrs Henderson and Paolozzi, in which an eclectic range of images – of textures, primitive statues, eggshells, skulls and other organic detritus – were hung from wires to create an immersive installation at the ICA. There’s Messrs Paolozzi and Henderson’s company Hammer Prints Ltd – which produced patterned wallpapers and textiles in which, says Mr Highmore “there is nothing to focus on, no repeated motif… like an elaborate, unending maze.” Then there is rumination on the the ethnography of bombed-out London in the 1950s (via the work of the Smithsons), an examination of Mr Paolozzi’s junk-filled humanoid statues and, finally, a critique of Mr Hamilton’s Gallery For A Collector Of Brutalist And Tachiste Art, an interior shown at the 1958 Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition.

In the course of such ruminations, Mr Highmore explains the importance of the brutalist concept of “as found” – that is, utilising objects and materials (whether junk, as in Mr Paolozzi’s sculptures, or concrete and steel, as in the Smithsons’ buildings) with a certain honesty, as they occurred in real life. Out of the analysis comes some interesting details – such as how the Smithsons’ 1950s flat housed perhaps the only ever living example of a brutalist bathroom, with its Paolozzi wallpaper and unadorned toilet chain hanging from the wall. (The couple were rather snooty, it turned out, when Mr Paolozzi arranged himself a subscription to the absolutely un-brutalist fashion magazine Vogue). Or how that the flattened, organic textures of brutalism might have been prompted by artists such as Messrs Henderson and Turnbull’s experience of gazing down at cities from the cockpits of RAF planes during WWII.

Overall, the impression is that brutalist art was more nuanced, substantial and charming than it has perhaps been given credit for (especially compared with its monumental, austere and undoubtedly better-known architectural counterparts). In short, for enthusiasts of architecture, art and mid-century design, Mr Highmore’s book fills in some important historical and contextual gaps.

The Art Of Brutalism by Mr Ben Highmore is published by Yale University Press

ROUGH TRADE

Keep up to date with The Daily by signing up to our weekly email roundup. Click here to update your email preferences