THE JOURNAL

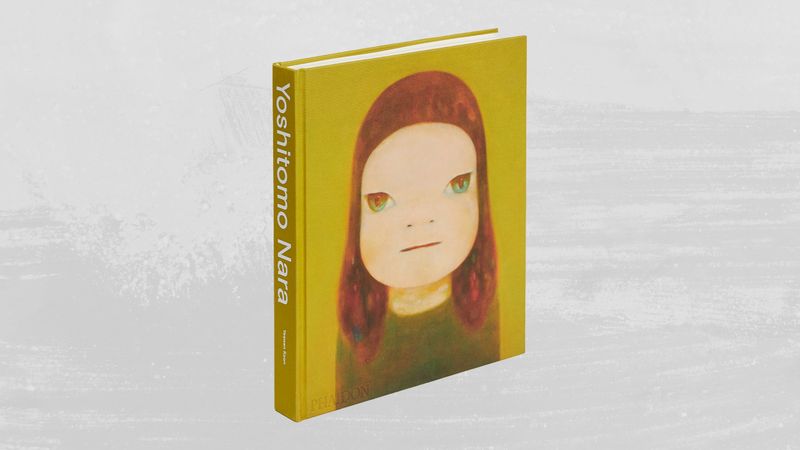

Yoshitomo Nara by Ms Yeewan Koon. Image courtesy of Phaidon

When I was little, my mother brought one of Japanese artist Mr Yoshitomo Nara’s works home. An oversized ashtray, it’s delicately lacquered with a little girl wearing a yellow smock – her eyes fixed in a glare and nostrils flaring – despondently smoking a cigarette, with the words “Too Young To Die” painted in a Comic Sans-like scribble on the rim. I couldn’t stop staring at it. Did a precocious child make it? Why was its subject so angry? Was it a piece of anti-tobacco propaganda? And, if it was used for its intended function, as my mother did, why would she, a smoker, want a ceramic reminder of her vice’s lethality? I just didn’t get it.

Years later, now armed with a master’s degree in art history, I still don’t. Not fully, anyway. Mr Nara’s work is deliberately ambiguous, and all the better for it. Hidden under a veneer of cartoonish simplicity, his now-iconic big-headed “girls” (Mr Nara has said he doesn’t consciously prescribe a gender to his subjects) are fascinating in their complexity. But a new book by Ms Yeewan Koon, chair of the fine arts department at Hong Kong university, and published by Phaidon, is the first major attempt to unpack the artist’s world.

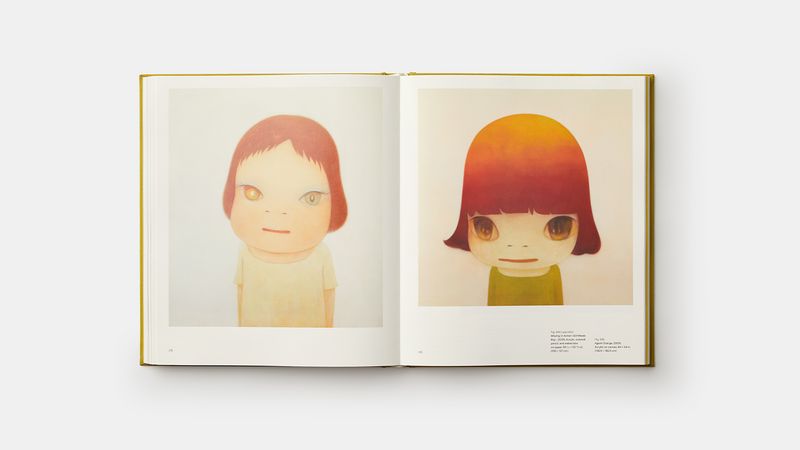

From left: "Missing in Action – Girl Meets Boy" (2005), by Mr Yoshitomo Nara. "Agent Orange" (2006), by Mr Yoshitomo Nara. Photograph courtesy of Phaidon

In it, Ms Koon charts how Mr Nara’s adolescence spent in post-WWII Japan laid the foundation for his highly nuanced aesthetic style. Though Mr Nara prefers not to categorise or classify his work, he remains one of the most prominent figures in the Superflat movement. A term coined by Mr Takashi Murakami in the late 1990s, Superflat refers to the output of a generation of young artists, Mr Murakami among them, responding to Japan’s burgeoning consumerist culture. Their pop-culture-inspired renderings are often attributed to isolated childhoods spent immersed in manga and anime.

Mr Nara has always been adamant though that his comic-book-reading years only tell part of the story, insisting that his work’s spiritual and philosophical elements are often overlooked or misunderstood. His formative years in his hometown of Hirosaki were spent playing among the local Shinto shrines, which often took the childlike form of Jizō Bosatsu, “a protector of children” Ms Koon writes. Later on, by the age of eight, when the musical influence of the US spread to Japan’s shores, Mr Nara had also developed a fierce passion for punk rock, the lyrics and cover art of which would come to figure prominently in his paintings.

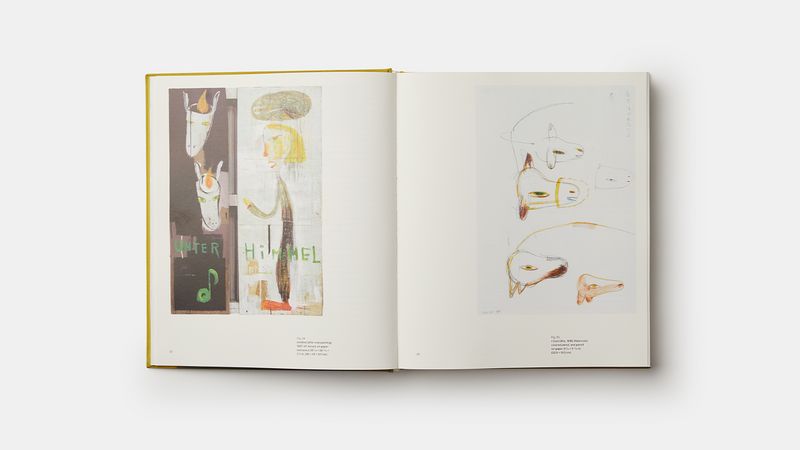

From left: "Untitled (after overpainting)" (1987-1997), by Mr Yoshitomo Nara. "I Can't Bite" (1989), by Mr Yoshitomo Nara. Photograph courtesy of Phaidon

Though he is now best-known for his complicated kawaii girls, the monograph also gives a detailed account of Mr Nara’s other artistic ventures. An astonishing assemblage of sculptures, sketches, installations, ceramics, collaborations and photography, its pages reveal Mr Nara’s extraordinary range and prolific output. It culminates in a chapter that examines the impact of the 2011 Fukushima earthquake and subsequent nuclear disaster on Mr Nara’s more recent work. After the tragedy, Mr Nara returned to the remote town in northern Japan where he grew up, and his work took on a more overtly political and emotional tone. “Over the last forty years, Nara has developed a distinctive voice in a career full of contradictions,” Ms Koon writes near the book’s close. “He is embraced by the art establishment, but finds meaning in smaller communities. His paintings project an aesthetic in which punk and cuteness go hand in hand. Categorically opposed to war, he is captivated by stories of wartime Japan. Nara revels in these contradictory positions.” Perhaps we’ll never figure him out.

Yoshitomo Nara (Phaidon) is out 18 March