THE JOURNAL

To celebrate the launch of Jaeger-LeCoultre, we challenged a virtuoso violinist to race through seven concertos. Roll over Beethoven .

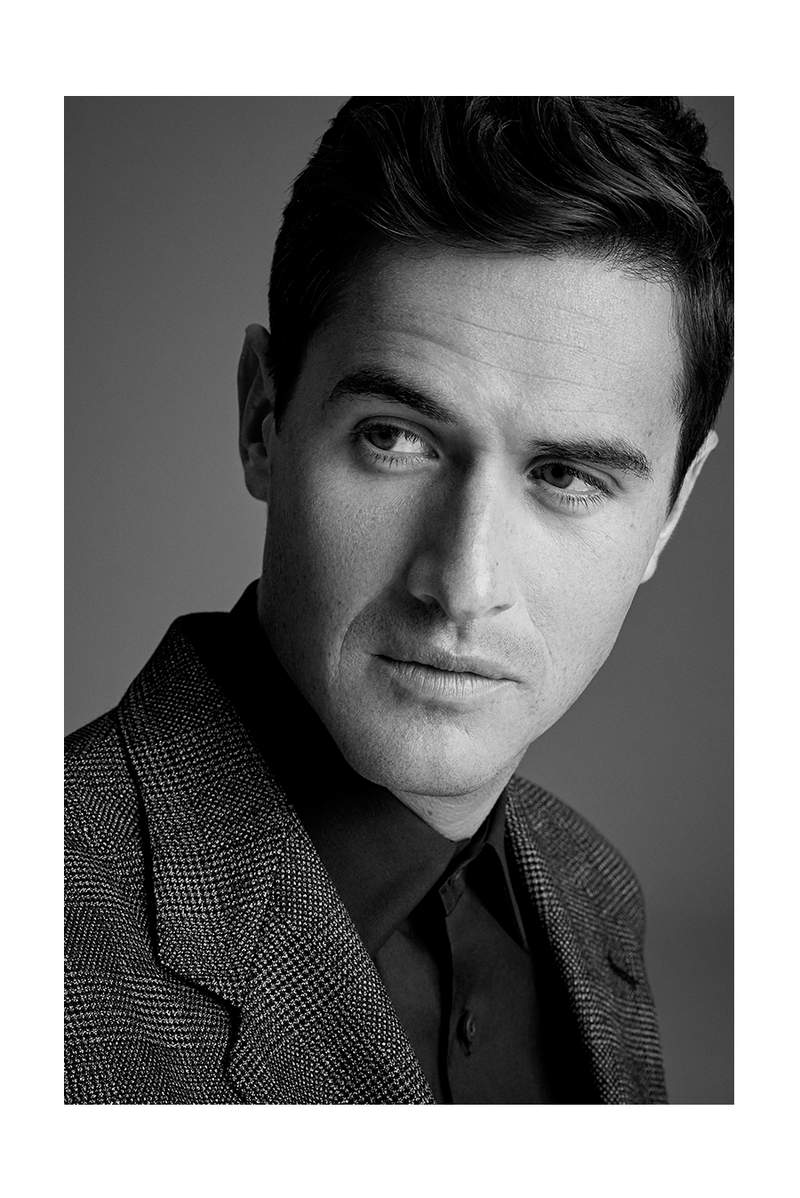

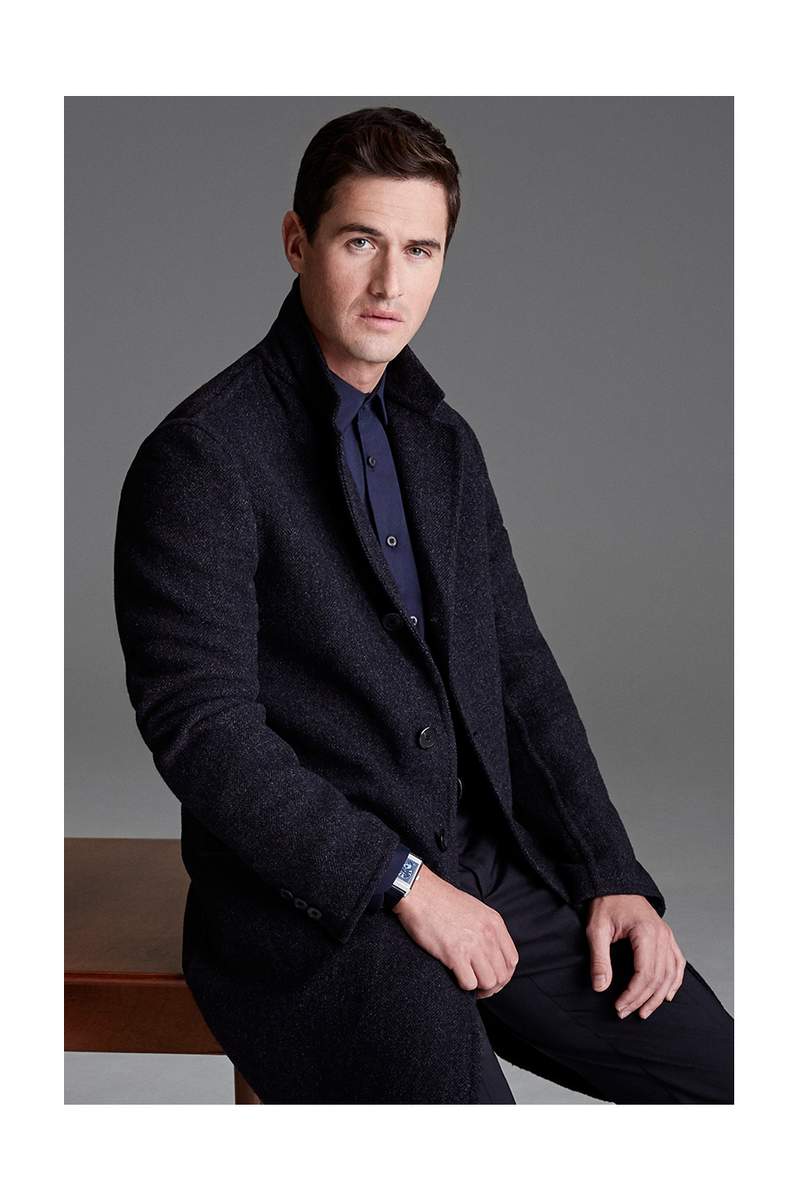

Mr Charlie Siem, the 31-year-old violin virtuoso, brand ambassador, musical collaborator to Ms Miley Cyrus, The Who and Ms Grace Jones and menswear industry darling, is explaining the esoteric concept of rubato. It’s an Italian musical command that translates, literally, as “robbed”, indicating that a performer may be taking unnecessary liberties with the articulation, dynamics and expressiveness of a piece for his or her own dramatic effect.

Most commonly, Mr Siem explains, rubato affects tempo, interferes with music’s timing. “And in classical music, timing is crucial. Every piece is notated with a very special time metre. If you are playing with an orchestra, you have to be aware of the clear sense of the rhythm and pulse that is present. If you go crazy, get lost in your own rubato and an over-extended interpretation, trying to make the piece your own by pulling and pushing too much, you take the time from the music and you can really mess up.”

The greatest musicians, Mr Siem says – people such as his violin heroes Mr Shlomo Mintz and Ms Ida Haendel (he’s performed on stage with both, by the way) – are the ones that can convey their own sense of drama, power and expression without changing what the composer has written. “It’s a very delicate balancing act.

“The beating heart of a watch is a good comparison,” he adds, likening the intricate machinations of an orchestra to a hand-built, wristwatch movement. “If you are one of 50 violinists in an orchestra, no one can hear you playing specifically, but everyone has their function and their part to play in creating an exceptional, collective sound.” No wonder, then, that this handsome, prodigiously talented young man, gifted with an acute sense of timing is the man helping MR PORTER to launch a brand known in the industry as the watchmaker’s watchmaker, which has made parts for some of the world’s biggest brands, from Cartier to Vacheron Constantin, for more than 180 years. A classic Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso hangs off Mr Siem’s slender wrist by way of confirmation.

Originally designed for polo players who would flip over its cleverly engineered dial to protect the oblong-faced crystal during a game, the specialist timepiece will now have to withstand the repeated rigours of a Mr Charlie Siem performance as he attempts excerpts of seven concertos in less than 40 seconds; the varying pressure and intensity of the left hand as it sculpts, curves and bends the notes. A bow stroke that he describes as “the breath” of the violin. Marque and musician working in perfect harmony.

The work/play, day/night concept of the Reverso also appeals to Mr Siem’s personal style. “Look at me,” he says tugging at his tracksuit bottoms and padded gilet. “I’m either really casual or super smart.” Casual tends to be luxe sportswear by Hugo Boss (he is a face of the German brand) while “super smart” is the bespoke suits he has made by Meyer & Mortimer, the military tailor on London’s Sackville Street. “I’ve been going there since I was 18 years old,” he says. “A couple of years ago, I designed my own concert outfit. It’s inspired by officer’s dress uniforms – a short, double-breasted jacket with a tail and a stand collar and an equestrian-type vent in the back for extra mobility. I button it up and wear a T-shirt underneath.”

Mr Siem might be in his Reeboks today, but for more dressy occasions, he looks to the dashing blazers and old-Hollywood tailoring of men such as Messrs David Niven and Errol Flynn. “Niven was so dapper – in the 1970s, he once came over to my grandfather’s house on Cap Ferrat in the South of France for a drink. I’m always asking my dad, ‘Where did he sit? What was he wearing?’”

Hungry for details and swashbuckling anecdotes, Mr Siem has been devouring biographies; Mr Niven’s The Moon’s A Balloon and Bring On The Empty Horses and Mr Errol Flynn’s My Wicked, Wicked Ways. He is currently engrossed in The Last Lion, Mr William Manchester’s massive three-volume biography of Sir Winston Churchill. His downtime is fairly Mr Niven-esque: he skies from the family chalet near Gstaad, Switzerland. Home is Monaco and an apartment in Florence, the frequent to-and-fro journey from principality to Italy made in his beloved new Porsche GT3 RS. Spirit-soaring Beethoven and Mahler blasting from the hi-fi, no doubt...

But Mr Siem is no playboy. Ever since he was a kid, he has been a highly disciplined character. A quitely antisocial boy of schedule, rehearsal and routine. Born into a family of wealthy Norwegian industrialists (his billionaire father Mr Kristian Siem was once dubbed Norway’s answer to Mr Warren Buffett), Mr Charlie Siem grew up near the Royal College of Music in London’s Kensington and attended Eton College. Prince Harry was a few years above him.

His musical epiphany occurred when he was still a toddler. Sitting in his mother’s VW Golf, he heard a rendition of Beethoven’s violin concerto on the car radio. “It was the first movement and I remember it well. The music moved me and made me want to learn how play it. It was a physical response. And I still get that. The music touches me profoundly, both physically and mentally. It enhances the imagination, it gives you your own story and your own, powerful experience. You become the music.”

By the time he was 11 years old, Mr Siem was already thinking about quitting school to take up music full time, rising at dawn to practice the violin for eight-hour stretches. “Deep inside, I had a calling. But it was a big challenge. I had to be very disciplined, practicing in break times and before school began.”

At first he played, at his own admission, “like a robot”, but gradually learned to relax and enjoy his instrument as he matured and grew ever more skilled. “I had to un-train myself. I had to create an environment where I could be completely free.” A handwritten note slipped into the velvet lid of his violin case reads “Keep it light and playful”. “Which is always good advice for me,” says Mr Siem. “I have a tendency towards… intensity.”

For Mr Siem, a performance is a pressurised situation. “Getting the best out of yourself is a learning process. You are different every time you perform and every concert is different. To mobilise myself, I need to clear out my mind. I meditate. I use little triggers – inspirational mottos from the Zohar, images of tigers, etc – that help me get me into the right state in mind. It’s process of discovery and hard to control – there is no one way of dealing with it.”

After playing for Royal Philharmonic and the London Symphony Orchestras, touring the world and winning the hearts of a global army of fans that call themselves Charlie’s Angels, Mr Siem’s big, cross-cultural break arrived courtesy of photographer Mr Mario Testino. “Mario had seen some videos of me performing and invited me to play at his book launch,” Mr Siem says. “The casting director for Dunhill was at the event and asked me to get involved in a new campaign [2011’s Voice]. It was very much a personality driven thing – me, an artist and Sir David Frost. What the fashion industry like to call ‘real people’, right?” he laughs. “I’m not a traditional model in that sense. Never will be.”

Mr Siem has since played violin for Giambattista Valli and Vivienne Westwood catwalk shows and at a party for Lady Gaga. Mr Bryan Adams invited him to duet on a special version of “Heaven” at the Royal Albert Hall and he has fiddled for rock legends The Who on a live rendition of the band’s classic “Baba O’Riley” at the same venue. He’s also worked with Messrs Karl Lagerfeld and Bruce Weber.

“I never thought that image and the way I dressed would become a part of what I do, but it’s actually helped open me up to a brand-new audience,” he smiles, adding a cautious, bashful caveat: “In the really serious classical world, there is a definite sense of apprehension and suspicion about someone doing all these glamorous things. I have to be careful because people can have pre-conceptions about me before they even hear me play; ‘We can’t imagine that he can be a good violinist or a serious artist if he’s doing all these photoshoots?’”

Well, for the rest of the us, it’s the opposite.