THE JOURNAL

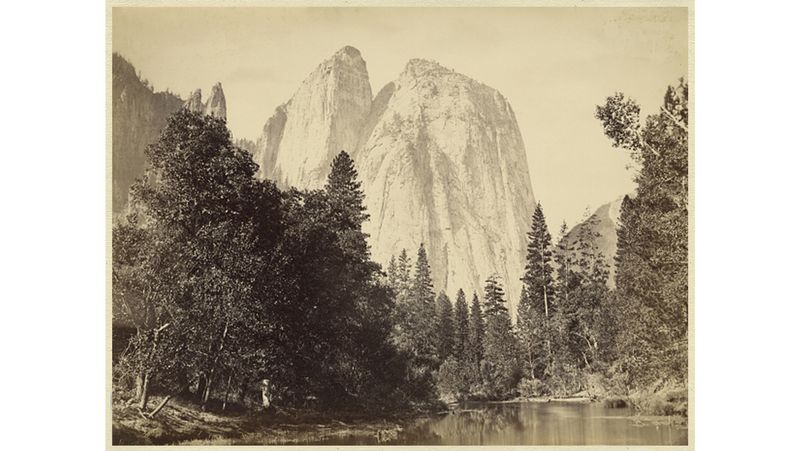

The Middle Cathedral Rock in Yosemite Valley, California, as seen from the river below, 1861 Carleton E Watkins/ Getty Images

Photographer Mr Carleton Watkins’ images inspired the world – and a US president.

Photographs can be powerful provokers. When words seem too considered and too complicated, sometimes only a photo can really bring home a message, be it a lonely polar bear clinging to a melting ice float, the devastating aftermath of earthquakes in Haiti and Nepal, or the plight of desperate immigrants at sea. But not all images rely on shock in order to prick the conscience of the masses. Sometimes, jaw-dropping natural beauty will do just fine.

As anyone who’s ever been there will tell you, nature’s majesty doesn’t come any purer than in the raw, core-shuddering vistas on offer at Yosemite National Park in California. It’s a region now famous for its breathtaking beauty and natural wonder. What few people realise is that had it not been for the artistic brilliance and technical skill of an unknown photographer (and the vision of a president) Yosemite may, like so many other areas of natural beauty, have been destroyed.

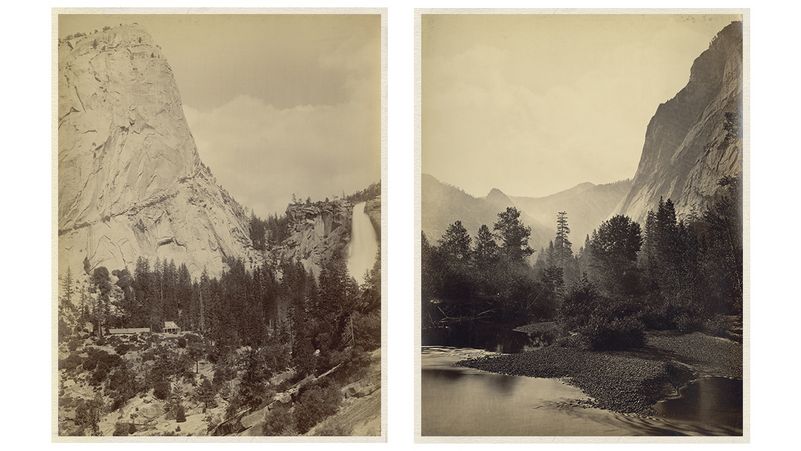

From left: Liberty Cap and Nevada Fall, 1865; Mount Starr King and Glacier Point, 1865 Carleton E Watkins/ Getty Images

The photographer we owe thanks to was a Mr Carleton Watkins, a New Yorker who first travelled to the Golden State in search of riches during the California Gold Rush in the 1860s. Like many deluded souls, the dream never materialised and, more by chance than by design, he turned his hand to photography. In the early 1860s, Mr Watkins began documenting the American landscape extensively, visiting everywhere from San Francisco to the Sierra Nevada. It was during this time that he created a series of photographs that would have a major bearing on the ecological legacy of the United States: his views of Yosemite.

Captured on what he called his mammoth plates due to their sheer size, producing these images required an unerring dedication to his art. Just getting in position required a team of mules loaded with his huge, custom-built stereoscopic camera, boxes of glass plates, tripods, a darkroom tent and all manner of photographic paraphernalia. On top of that there was camping equipment and supplies to last several weeks in the rough terrain and on the precipitous mountain passes of Yosemite. The mammoth plates were key in capturing the sheer beauty and scale of the area – every nuance and detail was recorded, and it is the clarity of the images and Mr Watkins’ genius for composition that make this series of photographs so groundbreaking.

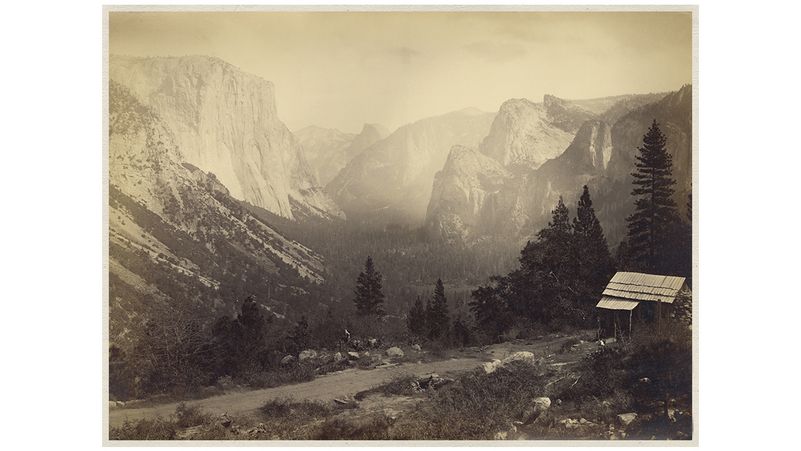

Looking east up Yosemite Valley from Artist Point, 1865 Carleton E Watkins/ Getty Images

The images produced were among the first photographs of the region to have been seen in the east of the country, stunning a public who had no idea of the natural treasures in their own back yard. They would also ultimately stir President Abraham Lincoln to pass legislation ensuring the long-term future of this then largely unexplored region of North America. The Yosemite Grant of 1864 forbade commercial development in the area and would later pave the way for the US National Parks system. Mr Watkins had unwittingly become one of the founding fathers of environmental photography.

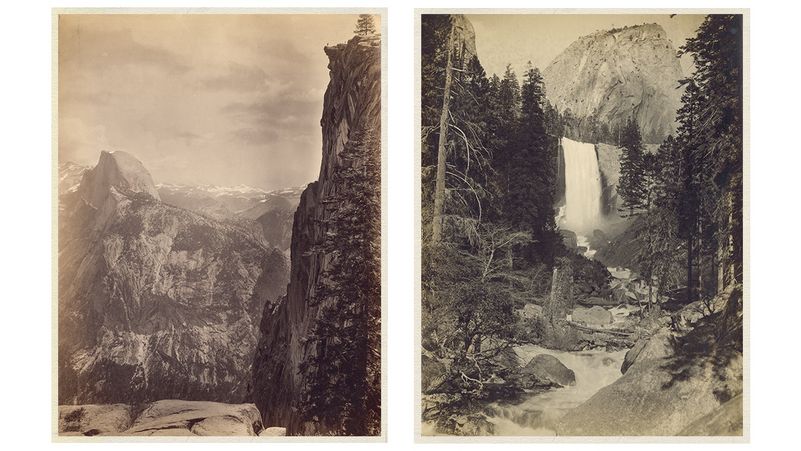

He would go on to spend the next two decades creating some of the finest American landscape photographs of the 19th century but, like many photographers of that era, he was a poor businessman. He went bankrupt on more than one occasion, at one point living in an abandoned railway carriage with his wife and two children. However, the final ignominy was ironically not of his own making and very much down to old mother nature. Mr Watkins’ studio was located in the heart of San Francisco when the massive earthquake of 1906 struck, which resulted in all his negatives being destroyed, together with most of his prints. With failing eyesight and a lifetime of work largely gone, these factors proved to be the tipping point for Mr Watkins and he was later committed to the Napa State Hospital for the Insane in 1910, where he passed away six years later. Like so many of history’s finest artists he died penniless and largely forgotten. It was not until a major retrospective of his work was held in New York in 1975 that the genius of Mr Watkins and his work was finally appreciated and his imagery heralded.

From left: Glacier Point and Half Dome, 1865; Vernal Fall on the Merced River, 1865 Carleton E Watkins/ Getty Images

With the human race seemingly intent on destroying the planet, you don’t have to look too far to come across the latest environmental outrage in the media, be it our disappearing rainforests, melting ice caps or animals on the verge of extinction. The cause of environmental conservation and preservation has been taken up by many – indeed a whole industry has evolved in an attempt to make us all sit up and take note. In Mr Watkins’ era it was a distant concern, which makes the emotive impact his work had on a president truly extraordinary.