THE JOURNAL

Commutes, cafés and car parks – how (and where) seven acclaimed writers penned their debuts.

The perfect circumstance in which to write a first book is pretty well mythologised: a room of one’s own; ideally, a private income; and – with a hat tip to Mr Cyril Connolly – absolutely no pram in the hall. Of course, it very seldom ends up like that. Most writers lack time, lack money, lack a room of one’s own and their halls – like it or not – will tend to fill with prams.

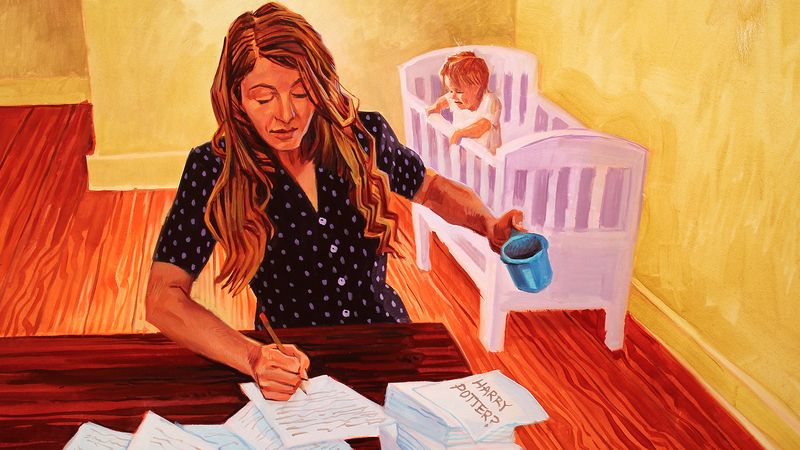

But writers are resourceful when books are crying out to be written. We might think, perhaps, of Ms Sylvia Plath hammering out the poems that were to go into her astonishing posthumous collection, Ariel, in the very small hours of the morning while her two infants were asleep. Or the Ukrainian dissident poet Ms Irina Ratushinskaya, who wrote poems in prison by inscribing them on bars of soap until she had them memorised, at which point they were washed away. Or, famously, Ms JK Rowling as a hard-up single mum writing Harry Potter And The Philosopher’s Stone (Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone in the US) while she eked out cups of coffee in Nicolson’s or the back room of The Elephant House café in Edinburgh.

New York novelist Mr Peter V Brett’s entire first novel was written on a smartphone on the F train between Brooklyn and Times Square

Mr William Faulkner, notoriously, wrote a good deal of his fiction while – at least theoretically – working as a postal clerk at the University of Mississippi. Eventually, the distraction caused by his day job got too much, and in the autumn of 1924, he finally wrote to his boss: “As long as I live under the capitalistic system, I expect to have my life influenced by the demands of moneyed people. But I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp. This, sir, is my resignation.”

Mr Faulkner was not alone – though he may have been in a minority by resigning. Any number of writers have sneakily completed their books on company time. Those with more commitment to the day job have endured punishingly late nights and early mornings. And for others there’s the commute – the New York novelist Mr Peter V Brett’s entire first novel The Painted Man (The Warded Man in the US) was written on a smartphone on the F train between Brooklyn and Times Square.

Mr Kingsley Amis once said that “the art of writing is the art of applying the seat of one’s trousers to the seat of one’s chair”, but history suggests that sometimes that chair might be on a bus, or a train, or even the seat in the smallest room in the house. At least there are no distractions there.

Mr John le Carré

Mr John le Carré wrote most of his first novel, Call For The Dead, on his commute to work as a “foreign servant”. “I have a great debt of gratitude to the press for this,” he told The Paris Review in 1996. “In those days, English newspapers were much too big to read on the train, so instead of fighting with my colleagues for The Times, I would write in little notebooks. I lived a long way out of London. The line has since been electrified, which is a great loss to literature. In those days it was an hour and a half each way. To give the best of the day to your work is most important. So if I could write for an hour and a half on the train, I was already completely jaded by the time I got to the office to start work. And then there was a resurgence of talent during the lunch hour. In the evening, something again came back to me. I was always very careful to give my country second best.”

Ms Joanna Cannon

The author of the bestselling The Trouble With Goats And Sheep wrote her novel while practising as a psychiatrist. “You grab what time you can,” she says. “I wrote most of it either at three in the morning before going to work, or with a laptop and a sandwich in my car in a wide variety of NHS car parks during my lunch breaks. Whenever people ask me for advice on how to write, I tell them: ‘Don’t do it like me.’”

Mr Philip Hensher

Mr Philip Hensher, who went on to be shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, wrote his first two novels in the House of Commons, where he worked as a parliamentary clerk, “while I was sitting around in the middle of the night waiting for the next division to be called on the Maastricht Bill. There was absolutely nothing to do, but you couldn’t go anywhere – the division could be called at any time.”

Mr JD Salinger

Mr JD Salinger spent WWII fighting in Europe, seeing some heavy action and being among the first liberators of Dachau. Nevertheless, he was clear about his priorities. He was already carrying manuscript pages of what was to become The Catcher In The Rye around in his knapsack, and his comrades-in-arms complained: “We always had to stop for Salinger to sit by the roadside, working on short stories or his novel.”

Ms Jane Austen

As a woman in what was then considered a man’s world, Ms Jane Austen was shy about her writing. The success of her first novel, Sense And Sensibility, did little to boost her confidence. Even as late as Persuasion, she was still self-conscious about being caught committing the dreaded act, and would hide her work whenever the squeaking door announced a visitor. She made a habit of writing on “very small pieces of paper so she could easily conceal the pages when interrupted”.

Mr Jean-Dominique Bauby

His first book, The Diving Bell And The Butterfly, was especially slow going. In 1995, Mr Jean-Dominique Bauby, former editor-in-chief of French Elle, suffered a massive stroke and was left almost completely paralysed. He composed and edited his memoir of his experience entirely in his head, and “dictated” it one letter at a time by blinking his left eyelid when an assistant, reciting each letter in the alphabet aloud, reached the letter he wanted. He went at about half a word a minute, for four hours a day.

Mr Gregory David Roberts

The author of the cult classic Shantaram was “writing continuously for 36 years”, but “for 20 of those years I couldn’t publish, because I was on the run for 10 years and in prison for 10 years”. He doesn’t recommend it. “I’ve written a novel and about 35 short stories in prison,” he says. “It wasn’t fun.” Among the setbacks he experienced was having his manuscript taken and destroyed not once but twice by prison guards. He advises aspiring writers to get a manuscript of a novel finished, then “put that first novel in a drawer, or have a prison guard confiscate it, or lose it while jumping through a window, and write another one, better than the first one”.

Illustrations by Mr Seth Armstrong