THE JOURNAL

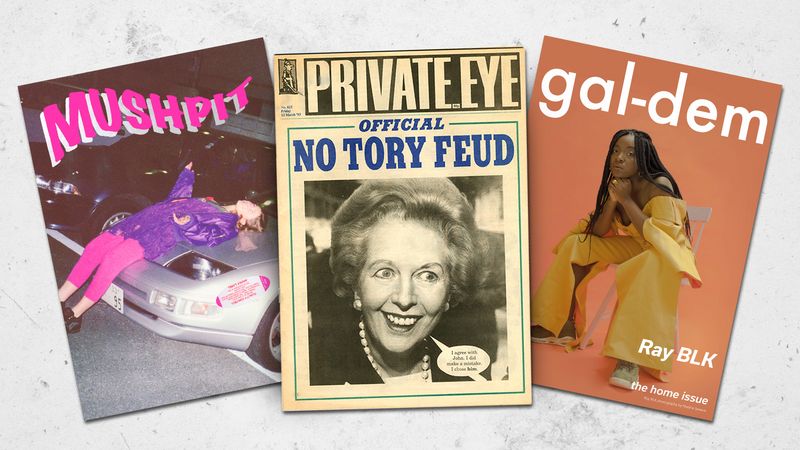

From left: Mushpit, Issue 9 “CRISIS”, 2016. Photograph courtesy of Mushpit. Private Eye, Issue 815, 12 March 1993. Photograph courtesy of Private Eye. gal-dem, Issue 2 “Home”, 2017. Photograph courtesy of gal-dem

An insight into the legacy of print publications.

Print is dead; long live print. That’s the message of Print! Tearing It Up, an exhibition celebrating the voracious DIY spirit at the core of UK magazine publishing. For curator Mr Paul Gorman, the recent closure of magazines like NME, FHM and Look has been met with a new burst of grassroots enthusiasm for print, spearheaded by young titles like Mushpit, gal-dem and Riposte. Those lamenting the so-called death of print should refer back to the late-1970s punk era, he says, when anti-capitalist energy powered a wave of vital underground record labels. Mining Mr Gorman’s personal archives, the Somerset House show (on until 22 August) traces this thread — from the snarling covers of original feminist bible Spare Rib to the independent-minded contemporary women’s magazine The Gentlewoman. “If you look at this era as post-2008, when the crash happened, and what’s happened in the music and film industries as well, it’s clear that creativity can’t thrive in the big-business corporate bubble anymore,” he theorises. A print journalist for more than 30 years and award-winning author of The Story Of The Face: The Magazine That Changed Culture, Mr Gorman has earned this sense of perspective, and is wildly positive about the future of print – as you can see in our Q&A with him, below. Walking through his vaulting display — laid out in collaboration with legendary Sleazenation creative director Mr Scott King — it’s hard not to agree with him.

**How did you pick the right magazines to tell the story you wanted to? **

“When we first started talking about it about two years ago, we didn’t want it to be backward-looking. There are lots of magazines being published today that are part of the lineage of The Face, but go even further back than that. So once we were certain it should feel [contemporaneous] we also knew we wanted to show the context, the lineages and history. We chose [radical literary magazine from 1914] Blast to kick it off, as the focal point was on the first modernist arts and literature magazines. From there it was a matter of joining the dots.”

What ties these magazines together?

“We knew the magazines should be progressive and independent-thinking, and they should cover the arts and politics. So we went from Blast to The Face, through to a lot of contemporary magazines. Then it was a matter of choosing between, say, Private Eye from 1961, or Time Out from 1968, or the underground press from the late 1960s — it gave us a spine through which we could tell the story. Having said this, we wanted to jumble it all together, so that Mushpit can rub shoulders with Private Eye; two magazines you wouldn’t necessarily put together, but which share lots of things in common.”

PRINT! Tearing It Up exhibition at Somerset House (8 Jun – 22 Aug 2018). Photograph by Doug Peters Press Association, courtesy of Somerset House

**Beyond tying these links, magazines can act as timepieces — a portal into a particular cultural context or moment... **

“I think that’s true. But also, it was to do with celebrating independence and independent thought, and the loss of that when big magazines are bought by big firms. For example, Time Inc. UK, which owned the NME, continued to produce the weekly print edition even though nobody really picked it up. It felt pretty devalued, but in a way they understood the value of print. But when Time Inc. was bought by a private equity firm, the first thing (the firm) asked was, “What the hell are you publishing this in print for?” They don’t understand the cultural aspect of it. If you look at this era as post-2008, when the crash happened, and what’s happened in the music and film industries as well, it’s clear that creativity can’t thrive in the big-business corporate bubble anymore. It’s taken us back to the post-punk flurry of indie record labels in the UK, which started with Stiff Records in 1976. I think in a way we’re in that kind of model in terms of independent print again, and that’s something we want to celebrate.”

What can you say about the direction new zines have taken? A lot of creativity seems to have a real political agenda to it now.

We wanted to point out the activism of zines, that what we’re looking at is often made by people who previously haven’t had voices, whether it’s younger women, or minorities, and people from trans and non-binary communities. This is probably one of the great aspects of our age. One of the interesting things is all of those [minorities] have gone to print to make their statement — whereas the alt-right are almost all online. Because if you commit to print, you’ve got to have a cogent reason for publishing something. The [alt-right] write all their stuff on Twitter, where they are constantly changing the goal posts. In the 1980s, The Face was always accused of being elitist — but actually it was very oppositional, particularly to the prevailing politics at the time coming from people like Thatcher and Reagan.