THE JOURNAL

Director Mr Barry Jenkins On Moonlight, Oscars And Reckoning With America’s Past

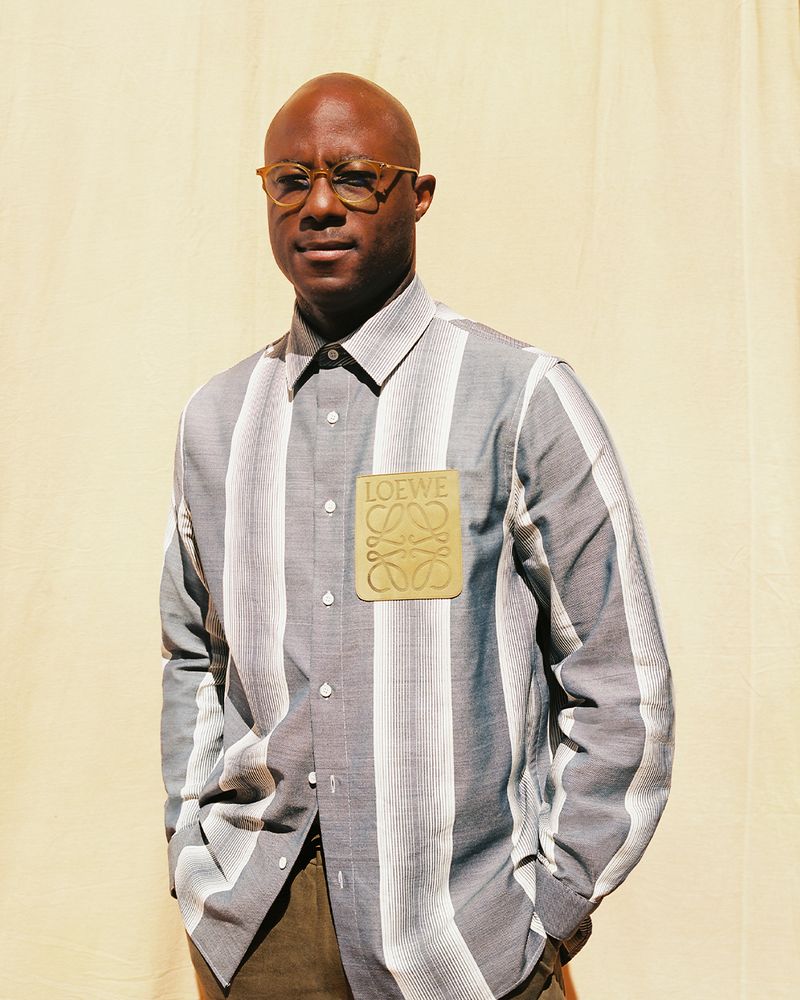

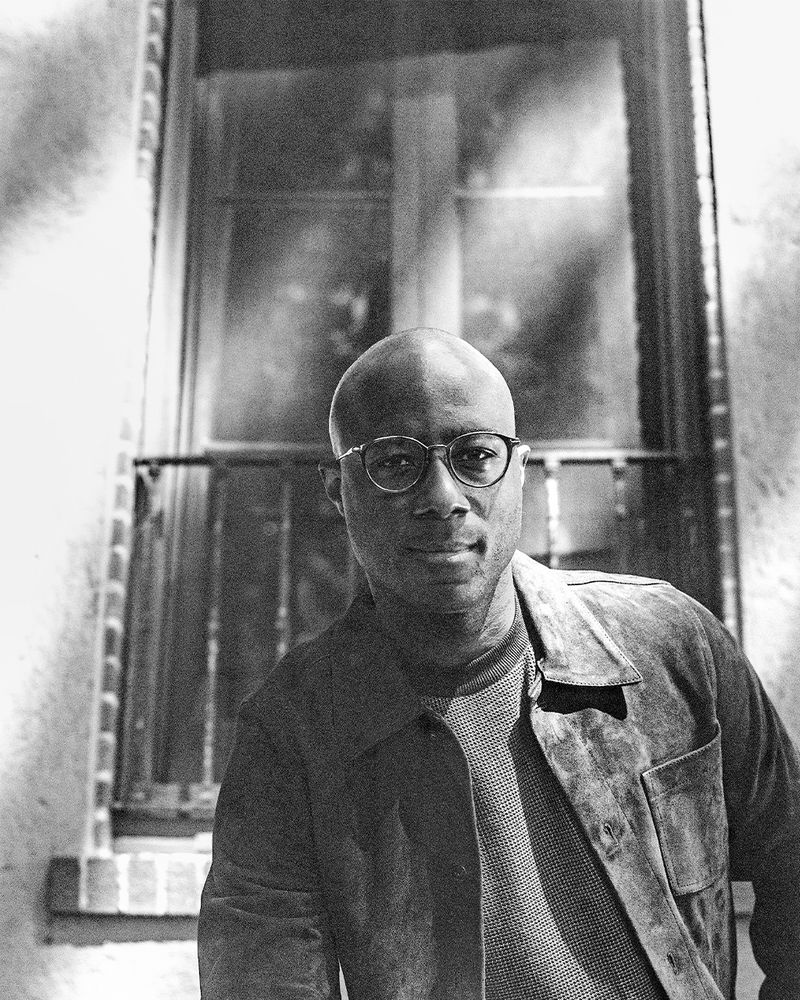

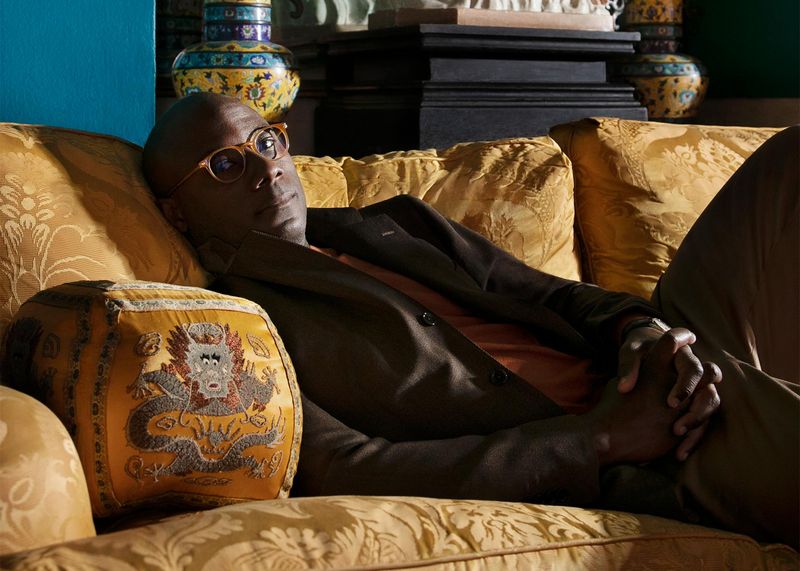

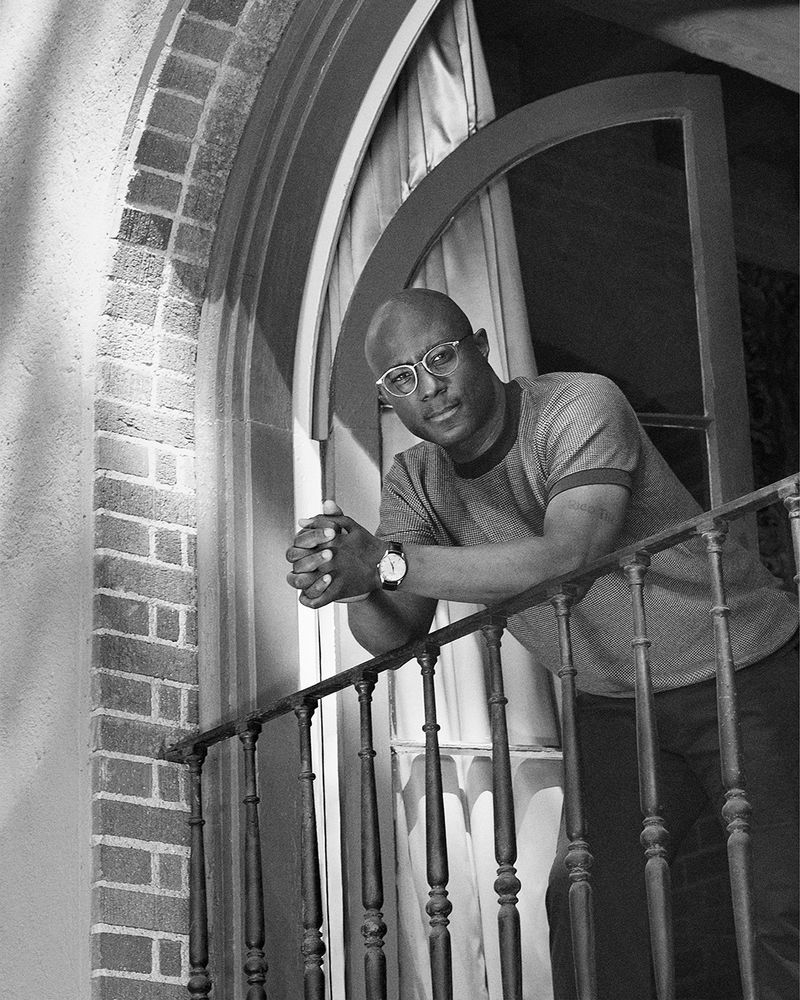

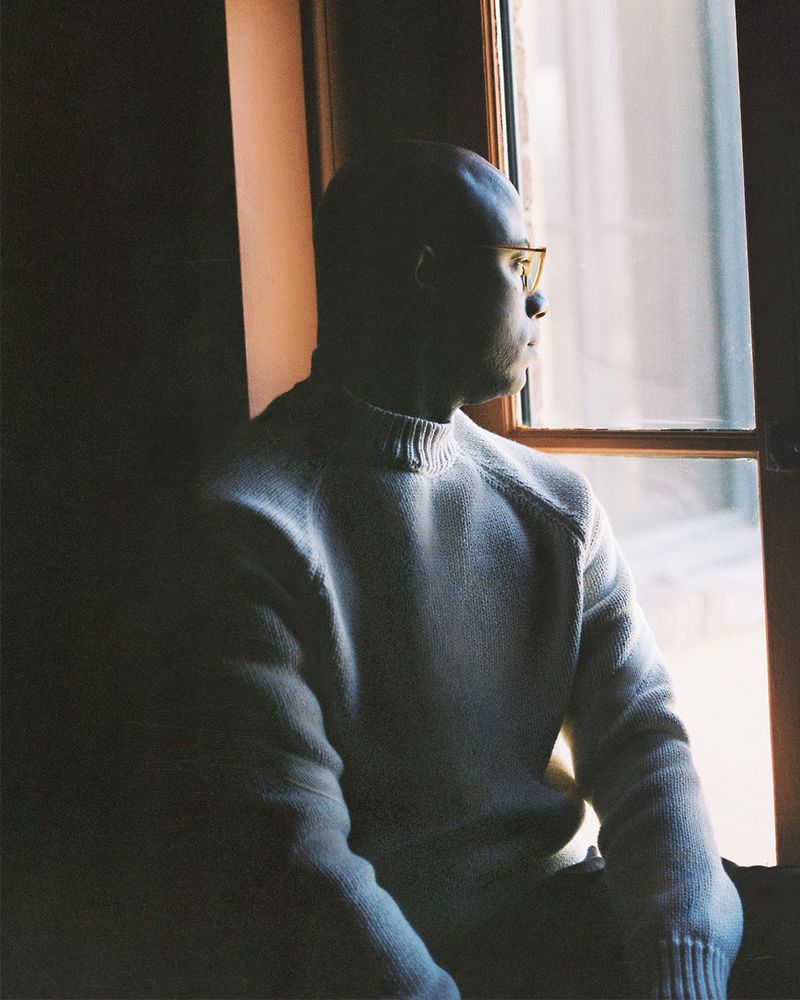

Mr Barry Jenkins, shot exclusively for MR PORTER, Los Angeles, 2021

In the space of just a few years, filmmaker Mr Barry Jenkins has won an Oscar for his masterpiece Moonlight, swiftly followed by more big-screen brilliance in If Beale Street Could Talk, and turned his hand to the small screen for his latest project, The Underground Railroad. Little wonder he is considering a break.

“I’ve ticked off those three boxes and, hell, maybe that’s all I have to say – now I’m going to go and teach,” he says with a laugh over Zoom. “I’ve just finished this six-year sprint, and I need to take a breath and either come up with a new list or just enjoy life for a little bit.”

The May release of Amazon Studios’ The Underground Railroad, an almighty 10-part adaption of Mr Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same name, completes a trio of triumphs in which Jenkins had determinedly set out to tell a personal story about where he grew up in Miami (Moonlight), adapt a Mr James Baldwin book (Beale Street), and explore the American condition of slavery.

In Whitehead’s bestselling alternate history, the Underground Railroad – in reality a network of clandestine routes and safe houses offering shelter and support to African-Americans escaping slavery during the late 19th century – is masterfully transformed into an actual rail transport system, which his protagonists use to flee from a plantation. The epic story follows Cora Randall’s unrelenting bid for freedom as the tracks and tunnels beneath the Southern soil and a steam train take her on the first chapter of a winding journey that reveals the true face of the US. Adapting this tale was the biggest challenge of Jenkins’ career to date – and his first time as a small screen showrunner.

“I’d spoken to Cary Fukunaga, who did the first series of True Detective, and Steven Soderbergh, who’d done The Knick, about the process and they both said it’s impossible,” Jenkins tells me, casually referring to the esteemed peers he consulted before commencing the show. “They said it was going to kill me, that it would be the most difficult thing I’ve ever done. And they were definitely right.”

Beginning in Georgia, the show traverses numerous American states as Cora gets closer to freedom with each new location reflecting another emotional state in her journey and consciousness. Each episode changes in both its visual and sonic aesthetic and – just as in Moonlight and Beale Street – the profoundly evocative music, composed by Mr Nicholas Britell, perfectly complements the narrative. For his TV series, Jenkins naturally called on his close-knit circle of collaborators, many of whom he met more than 20 years ago while studying film at Florida State University College of Motion Picture Arts.

“I also found it really invigorating,” he asserts of the process. “We shot the show over 116 days and because of that there’s a rhythm you fall into, both with the characters and the crew.”

The ensemble cast, led by South African actress Ms Thuso Mbedu, is a potent mix of relative newcomers and stalwarts of screen and stage. The casting – which pulled performers from London, New York and Los Angeles via Louisiana – is a beautiful depiction of the sprawling African diaspora. Each actor brings their personal experience and cultural nuances to their part: “Everyone had a little bit of a different perspective on where they saw their direct connection to this story.”

When Jenkins and his team first began work on The Underground Railroad, Mr Barack Obama was still the president of the US. A few months later, Mr Donald Trump came into power with his militant dictum to “make America great again”. This only amplified Jenkins’ desire to probe the nation’s dark history of slavery and deep-rooted racism. “America hasn’t always been great, there have been some heinous practices on Black people, women, Asian people… How can you say ‘make America great again’ without acknowledging those things?” Jenkins asks. “The show was very clearly speaking to this idea of the need to acknowledge these problems of America’s past.”

Just as the project was drawing to a close, the world was halted by the Covid-19 pandemic and filming came to an abrupt stop. A couple of months later, following the killing of Mr George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement surged globally. As protests raged outside and on social media, Jenkins was editing the show, pondering how he might have told the story differently to reflect the rising global outrage in the face of systemic racism, police brutality and violent misogyny.

“In May, I thought if we could go back and rewrite this show, I would make it say so many things about the present moment, but I didn’t have that luxury, so we kept editing and it became clear that it’s already speaking to so many of these things. Why? Because they’ve always been there. It didn’t take on an increased importance, but it brought into sharper focus the importance of what we were doing.”

Over the past five years, the Black experience – or rather Black pain and suffering – has been at the centre of film and television narratives seeking to tell Black stories, prompting many of us to question this continued focus on Black trauma. But with The Underground Railroad, and despite the harrowing truths within Whitehead’s novel, Jenkins wanted to remind the viewer of the humanity and singularity of the Black characters in his story.

The result is certainly not a reductive portrayal of the mass experience of slavery. Instead, Jenkins masterfully brings to life the love, hope and ambitions of the individual characters. The essence of this mission is poignantly distilled in a series of lingering shots and portraits in several episodes that capture the cast breaking the fourth wall to stare directly at the viewer.

“These direct-to-camera moments that primarily feature background actors,” Jenkins explains, “was my way of presenting something that completely removes the white gaze. It’s just myself and you, the ancestors, whomever, getting to look directly into themselves. It’s interesting because a lot of those moments don’t advance the plot of the show and yet I can’t imagine it without them.

“[The main character] Cora is a woman who suffered the misfortune of being enslaved and what I love with these portraits is any of these background characters could also have a 10-episode series about their lives,” he continues. “There’s a story here, there’s a story here and there’s a story here,” he gesticulates emphatically, his passion palpable. “I do think that they all deserve to be told.”

Jenkins’ storytelling is an exquisite blend of style and substance. Moonlight was an utterly compelling portrait of masculinity; If Beale Street Could Talk had a mesmeric lushness and soul-piercing power. So, when talk turns to the filmmaker’s personal style, it is perhaps unsurprising that he speaks with continued enthusiasm.

“Fashion does excite me personally,” he says. “For a brief while, I was acquaintances with Raf Simons and got to spend a little time with him. Architects and fashion designers are the people whose process I find myself gravitating towards. As an artist, I love the approach to art making in that realm. As someone who wears clothes, I wear stuff that I feel is comfortable. I don’t think that I’m fashionable, but I find myself gravitating more and more to things that have a story.

“I have more coats in my closet than any man should be allowed to wear,” he jokes. “And more leather Italian boots. I love putting something on my body that I know someone took their time to create. The same way I hope that when people sit down to watch the show, they feel like Barry Jenkins and his collaborators really took their time thoughtfully creating this thing.”

Jenkins made his name with Moonlight, the coming-of-age story about a gay Black man living in Liberty City, Miami. After the film won Best Picture at the Oscars in 2017, Jenkins’ status as one of Hollywood’s most vital talents was cemented, a status that’s only set to rise. “I’m not a celebrity, but I do realise that I have a public profile, which is growing with each of these projects. I feel like people like myself, or certainly people who are much more famous, our experiences and opinions are sometimes given excess weight. I’ve actively tried to be self-aware and understand where it’s appropriate and where I need to say something.”

“America hasn’t always been great, there have been some heinous practices… How can you say ‘make America great again’ without acknowledging those things?”

He acknowledges that “we have a responsibility to not take up too much space,” alluding to his desire to make room for newcomers and underrepresented voices. When it comes to representation in film, Jenkins feels positive about the developments he has seen over the past decade. “From when I started in Hollywood, around 2008 to now, there’s been extreme progress. The fact that this year we had two women nominated for Best Director and two men of Asian descent nominated for Best Actor for the first time [at the Oscars], the proof is in the pudding.

“There have been moments in Hollywood, where it seemed like the Black vanguard, or the Black new wave had arrived and then we slowly saw members of this group of filmmakers gain less and less traction. It doesn’t seem to be the case right now. Ava [DuVernay], Ryan [Coogler], Jordan [Peele] and Issa [Rae] are four of the most successful people of any race in Hollywood right now. Who would have thought seven years ago that any of us would still be here and be on our first or second feature?”

Chauncey, the dog Jenkins shares with his partner and fellow filmmaker Ms Lulu Wang, pops into the corner of the screen, momentarily interrupting our interview. Wang is an award-winning writer and director, whose critically acclaimed 2019 film The Farewell deftly delves into familial love, the immigrant experience and the differences between Western and Chinese family values. I ask Jenkins about the dynamic between the two immensely talented creators, who were introduced by a mutual friend in the industry.

“The biggest thing is living with someone who understands the mental stress that you are often going through,” he says. “It’s hard for anyone to understand why someone is making something, and the both of us understand why we’re creating the things we’re creating. As we give feedback, it’s from this other, much softer place… With this show, she’s been very good about allowing me the space to go to these very dark places.”

He pauses, gazing out onto the stretch of grass beside the veranda he is sitting on. With visible adoration, he adds: “I’m looking at her now, she’s out there playing with Chauncey.”

Rumours abound that Jenkins is developing a documentary with Mr Leonardo DiCaprio and his earlier talk of a career break is debunked when he confirms the current projects he is in fact juggling, including a live-action prequel to The Lion King. “We’re developing a third series of The Knick and I have the film about the life and times of Alvin Ailey that we’re working on now. But I’m not writing any one of those three,” he says firmly. “I’m just the director, which is a whole new process and experience for me. Maybe that’s the new phase of my career.”

Whatever that new phase may be, we’ll be keenly watching.

The Underground Railroad is on Amazon Prime Video now