THE JOURNAL

“It took me a long time to figure out a way to get out here,” says Mr Avi Brosh, pouring coffee in the airy kitchen of his Malibu home on a particularly idyllic November afternoon. His journey to one of Los Angeles’ most rarefied neighbourhoods – and his position as one of the fastest-rising hoteliers in the US – has been, by any standard, quite remarkable.

Over the past 15 years, Brosh has opened 19 hotels under the Palisociety brand, with another four set to open in the coming months. Each one is distinct in its aesthetic and ambience, veering from motel-style rooms that look out onto open-air pools to more homely, expansive spaces intended for longer stays. But they are united by their aim: to offer an elevated experience for an urbane, discerning clientele, without the eye-watering bill of his competitors – by trimming the service proposition to a more casual, down-to-earth approach.

Brosh has lived at his Malibu home for a little over 18 months. Like his hotels, it deftly straddles the luxurious and the relaxed: a curious hybrid that he describes as “half beach house, half farmhouse”. The two-level cottage set against a vista of the Pacific Ocean attracted Brosh’s attention precisely because it felt so distinct from its surroundings. “When you drive around Malibu, a lot of the houses feel very nondescript,” he says. “There’s not much around here that’s architecturally significant.”

Built in 1941 (when this part of Malibu was “the middle of nowhere”), it had fallen into significant neglect when Brosh acquired it. “It felt very twee, very cheap and cheerful, very 1990s,” he recalls. “With really bad bathrooms.” But his wife, a former stylist and director who now oversees the branding elements of Palisociety, felt confident they could restore it to its original charm. “We’re in the business of taking terrible old buildings and redoing them,” he says. “And besides, we already had a lot of stuff.”

Today, its style could best be described as Cotswolds-meets-California. Touches of English design run throughout the space, from the white roses that grow outside the front door to the antique silver trays and imported bronze taps that Brosh acquired over the course of his career. But the house is scattered with West Coast touches, too – not least in the white wooden panelling that covers much of the interior – though he’s no fan of the “traditional” LA style of cavernous spaces with minimal design detail.

“No, no, no,” he says. “I guess we’ve done things that are counterintuitive. We certainly haven’t designed this place with an eye on resale value. But this has been my style, and my wife’s style, for our whole lives. We did the whole ‘big house’ thing before. And, once you do it, you realise you spend most of your time in three rooms. There are dining rooms people have never even been in. So, I wanted something smaller, and more human, and more organic.”

Brosh opened his first hotel in 2007, alongside a host of other business and real estate interests. But the recession of 2008 put paid to almost all of his other ventures, while the hotel – despite Brosh’s relative inexperience – survived. “I took refuge in that,” he says. Brosh credits the success of his brand to his “left-brain-right-brain” approach, which balances the strong creative direction needed to differentiate the brand and the business acumen to bring it to life. “The idea that you can have a vision and say, ‘We’re just gonna lose money for a while until we figure it out…’ I think the jig is up on that,” he says. “I think you have to make money.”

Still, there were learnings. He recalls, at the start of his career, hoping to know every member of his staff by name. But with upwards of 4,000 people coming in and out of his hotels daily, it’s become impossible. “It’s just the sheer number of humans coming through your life,” Brosh says. These days, he tries to visit each of his hotels twice per year, sampling the restaurants and bars (“I try to keep the drinks simple. No one wants to drink a ‘Blue Pussycat’”) and inspecting the properties to ensure they are well maintained. Scuffs, in particular, are a bugbear: “I hate them,” he says. “I take them so personally. They make me completely crazy.”

Despite his rigorous standards, he has pushed hard for a hands-off approach to service – something that sets his spaces apart from most of the market. “It’s harder than you think,” he says. “It’s a real art form.

“In America, there’s a certain quality of service at most hotels. There’s a lot of, ‘How’s your day going?’ And that’s just too exhausting for most people. Just flash a smile and let them know you’re there. But don’t be annoying.”

“If you create something with a singular point of view, it’s like a guest room in your house”

He’s taken a highly personal approach to his hotels’ interiors, in contrast to the retro-beige aesthetic of so many American hotels. He credits this to his own single mindedness. “You can’t design by committee. You know, you sit in a room with 10 people discussing it, and by the time it gets delivered it’s a little bit of everything.

“But if you create something with a singular point of view, it’s like a guest room in your house. If you do it that way, it doesn’t feel so transactional. Because if you have a guest at your house, you don’t ask them to pay.” He pauses. “Well, hopefully not.”

That sense of idiosyncrasy is evident across Brosh’s own home, too. For all the hotel-like touches – the artfully arranged glass jars of conch shells on an end table, the broom cupboard converted into a bar, the Diptyque products in every bathroom – there are curious quirks. Dog-shaped bric-a-brac litters the property, from salt shakers to doorstops, in a nod to their own pet, the only other resident since Brosh’s own children have since left home.

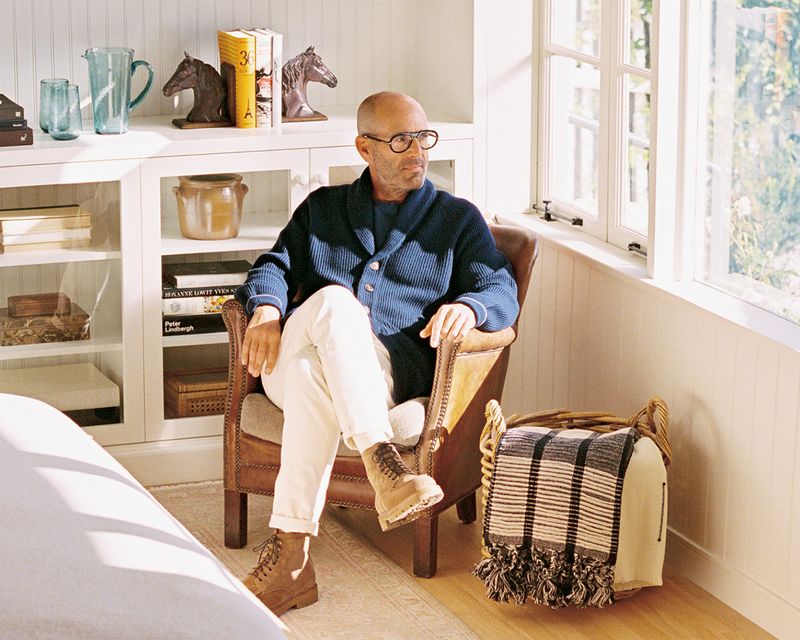

His own style is rather less eclectic. Brosh’s wardrobe is, per his own description, “variations of navy blue”: blazers, slacks, shirts and lightweight knits. He considers the uniform a necessity, given the multifaceted nature of his role. “It means it doesn’t matter if I’m just going to drop something off, or if I’m going to meet the team, or if I’m going to meet potential investors. It’s always the same.”

Besides, he’s a stickler for personal presentation, and is quick to spot those who don’t make the same effort. “It’s like they’re giving different energy to a different group of people. That’s not the way I do it. I give people the same respect with my presentation no matter whether it’s Monday at 9.00am or a cocktail party.”

The week after we meet, Brosh has a new property opening in Tampa. He’s not nervous – for one, the people are “shockingly nice”. And besides, he says, “for better or worse, you learn how to do it. You make enough mistakes to learn what not to do the next time around.”

After that, he’ll begin winding down for the holidays, when his kids will come out to the house to visit. “It’s the best time to be in Los Angeles,” he says. “It’s quieter, everyone is out of town, the weather’s great.”

He’s not a fan of hired-in catering; he will instead spend the season hosting and cooking for friends and family. “I’d much rather be chatting with you in the kitchen, pouring you drinks. There’s a certain casualness that makes people more comfortable,” he says. “I’d much rather be in it.”