THE JOURNAL

Noma chef Mr René Redzepi. Photograph by Mr Jeff Gordinier, courtesy of Icon Books

Danish chef Mr René Redzepi is never far from hyperbole. The New Nordic pioneer has been pushing boundaries since he launched Noma in 2003, a restaurant that has topped the World’s 50 Best Restaurants list four times with its focus on foraged seasonal ingredients and traditional techniques, such as fermentation. The waiting list has, at times, numbered 10,000, its concept has inspired a raft of copycat restaurants and a generation of trainee chefs are prepared sacrifice everything to work alongside its founder.

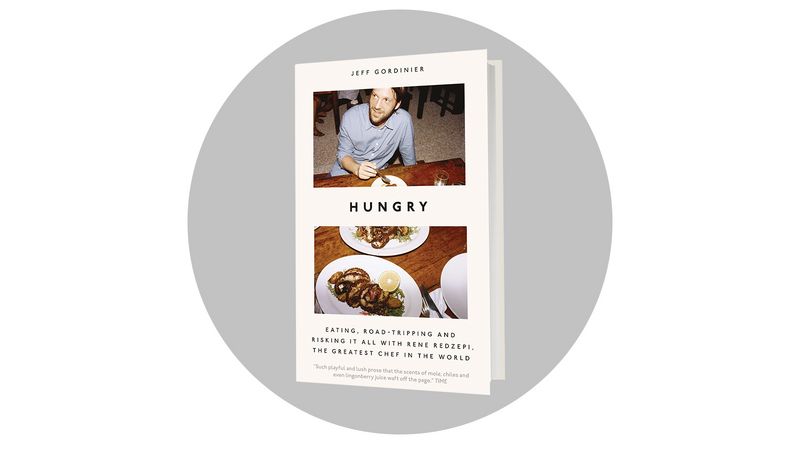

Writer and journalist Mr Jeff Gordinier has spent a lot of time in Mr Redzepi’s orbit. An interview with the chef in 2013 led to a sprawling four-year adventure trailing him around the world in search of inspiration for a series of Noma pop-ups, which has now become a book. Hungry: Eating, Road-Tripping And Risking It All With René Redzepi, The Greatest Chef In The World paints a fascinating portrait of Mr Redzepi and his inner circle while exploring food culture, fanaticism and how, despite his Macedonian heritage, he became a poster boy for Scandinavian food. Here we pick out five key teachings from the visionary chef.

Embrace outsiderism

The son of a Macedonian Muslim immigrant, some of Mr Redzepi’s strongest memories stem from a period spent living in Macedonia as a teen, where he churned butter, milked cows and kicked off his passion for foraging. According to Mr Gordinier, the chief architect of the New Nordic movement had a complicated relationship with what would stereotypically be seen as Nordic. “He portrayed himself as more of an interloper than a native,” he says. “For those who happen to notice that his kitchen at Noma was staffed with and powered by immigrants, it’s useful to remember that Redzepi always viewed himself as one. He was drawn to those cooks who seemed to come from a place outside of the establishment.”

Use local ingredients

For Noma’s Australian pop-up in 2016, Mr Redzepi doubled down on his principles by placing indigenous ingredients at the heart of his menu. “We are dealing with things that are as old as time itself,” he says, referring to Australia’s vast natural resources. “They’ve had a way of cooking and surviving for thousands of years.” He enlisted the skills of forager Mr Elijah Holland, who picked wild figs from Sydney’s suburbs and watercress snipped from Bondi Beach, which, says Mr Gordinier, although “utterly negligible to the people who lived yards away from them, would be incorporated into a dish at the best restaurant in the world”.

Learn from the experts

Ahead of his $600 tasting menu at the Mexican pop-up in Tulum in 2017, Mr Redzepi zigzagged between Oaxaca and the Yucutan Peninsula for inspiration. “The complexity of Mexican cuisine – the corn, the chillies, the fruits, the edible insects, the sharp differences from region to region – haunted him like a love affair whose memory he couldn’t shake,” says Mr Gordinier. Perfecting a mole became an obsession following a visit to Mr Enrique Olvera’s restaurant, Pujol. The Mexican chef’s slow-cooked take on the traditional sauce sparked Mr Redzepi’s mission to perfect his own. “I’ve just got to figure out what it is,” he says. “Finding new flavours excites me tremendously.”

Keep cool in the kitchen

While practising the art of tortilla making, Mr Redzepi reflected on his career. Not usually inclined to hide his anger in the kitchen (Mr Gordinier recounts the time he allegedly marched every member of the Noma team out of the kitchen, lined them up and screamed, “Fuck you!” into each individual’s face), things changed following Noma’s almost career-ending norovirus outbreak in 2013. “The future is not any more of that screaming,” he says, recalling a time when he woke up covered in stress-related shingles. “I used to be so angry in the kitchen. A monster. I made a decision. What the fuck am I doing? You have to make a choice. Do you want to go to work and be miserable? Or be happy?”

Keep innovating

“Couldn’t the guy just coast for a while?” asks Mr Gordinier while considering Mr Redzepi’s years of obsessive labour raising Noma from obscurity to what’s often described as the world’s best restaurant. “I could take it easy at Noma,” says Mr Redzepi. “I could just stay put and do what we do there. But I genuinely think we won’t progress.” As Mr Gordinier comes to realise, he’s aiming higher, willing Noma to become something that achieves a level of cultural permanence. “For that you need to be daring,” says Mr Redzepi. “If you want to keep your mind young, you have to keep moving.”