THE JOURNAL

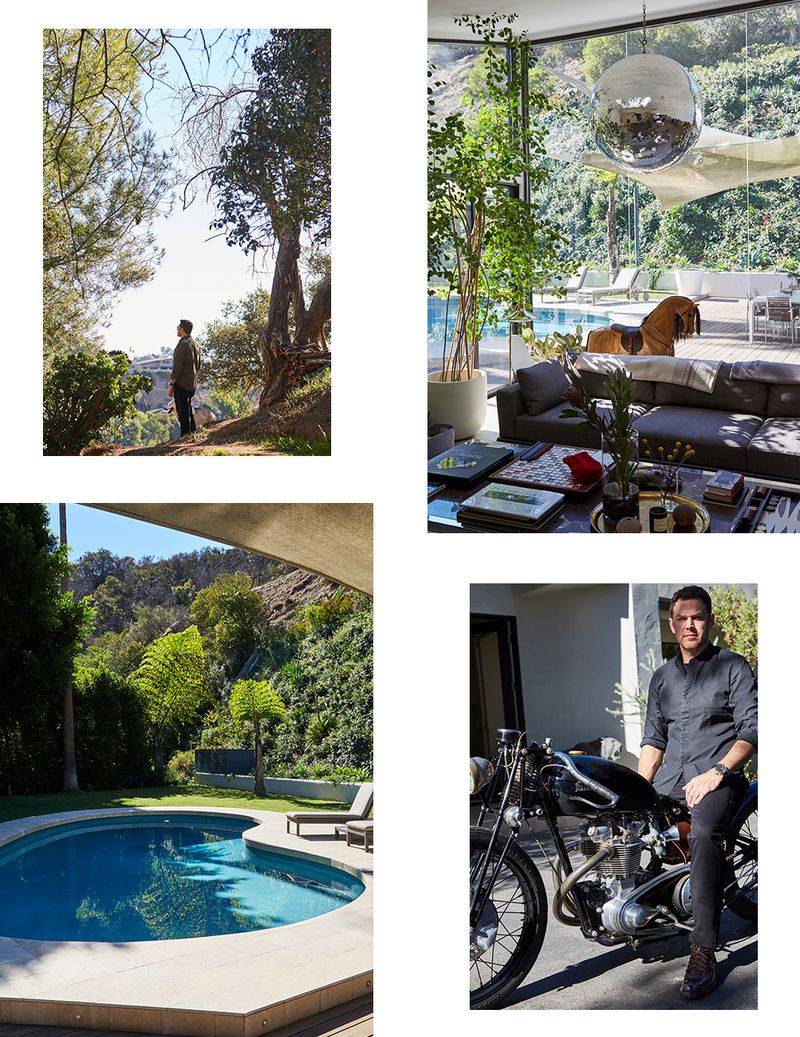

In association with IWC Schaffhausen, we spend a day in LA with motorcycle designer and sculptor Mr Ian Barry.

It all started with a recurring dream, says Mr Ian Barry. “I must have been about four or five. I was able to hover just above the ground and dart around the place.” The feeling of flying stayed with him for years, but, try as he might, he could never recreate it while awake. Until the first day he rode a motorcycle, that is. “It felt like time collapsed and I was back in the dream.” Since then, the MR PORTER Style Council Member has channelled his passion into first, modifying, and eventually, making his very own museum-worthy bikes from scratch.

When we meet at his home and studio overlooking sprawling Los Angeles, the day is idyllic, even by SoCal standards. Though it wasn’t the weather that convinced Mr Barry to move there 20 years ago; it was the city’s singularity. Smaller towns with smaller mindsets might be quick to shoot down out-of-the-box ideas, but not LA. There’s nowhere like it, he says. “It’s the breeding ground for out of the ordinary in the most fantastic and great ways… and some dark ways, too,” he adds. “When you start to connect with that fantastic side, there is no ceiling, and that’s intoxicating.”

It’s in this one-of-a-kind metropolis that Mr Barry began work on the famed Falcon series, a 10-part project based on rare British engines he embarked on a decade ago with his wife, Ms Amaryllis Knight. It’s an undertaking that’s cemented Mr Barry’s work as the pinnacle of manufacture and set the bar – artistically, aesthetically and mechanically, speaking – for other designers. “Falcon is an ongoing project, it never really ends,” Mr Barry tells us. But as the venture approaches the midway mark – the soon-to-be-released Vespertine will be the fifth cycle in the sequence – he’s switching gears and focusing his efforts on electric bikes. “Pun intended,” he jokes. “There are no actual gears on an electric.”

“The White", 2013, by Mr Ian Barry

All kidding aside, for proponents like Mr Barry, electric isn’t a niche or novelty; instead it represents a brave new world. But the industry shift has earned itself some detractors who think that these technological leaps and bounds somehow negate the heritage and nostalgia associated with combustion engines. “Nostalgia is a very interesting word. I’ve been strapped with that label,” he says. “But for me it was never really about that. The choice to use certain engines was about their timeless quality. I’m interested in forms of design that seem to exist outside of time periods.” Achieving that timelessness, according to Mr Barry, is about looking forward and back: “You can definitely take some hints from what’s been done with two wheels before, but in a lot of ways it’s a completely undiscovered mass.”

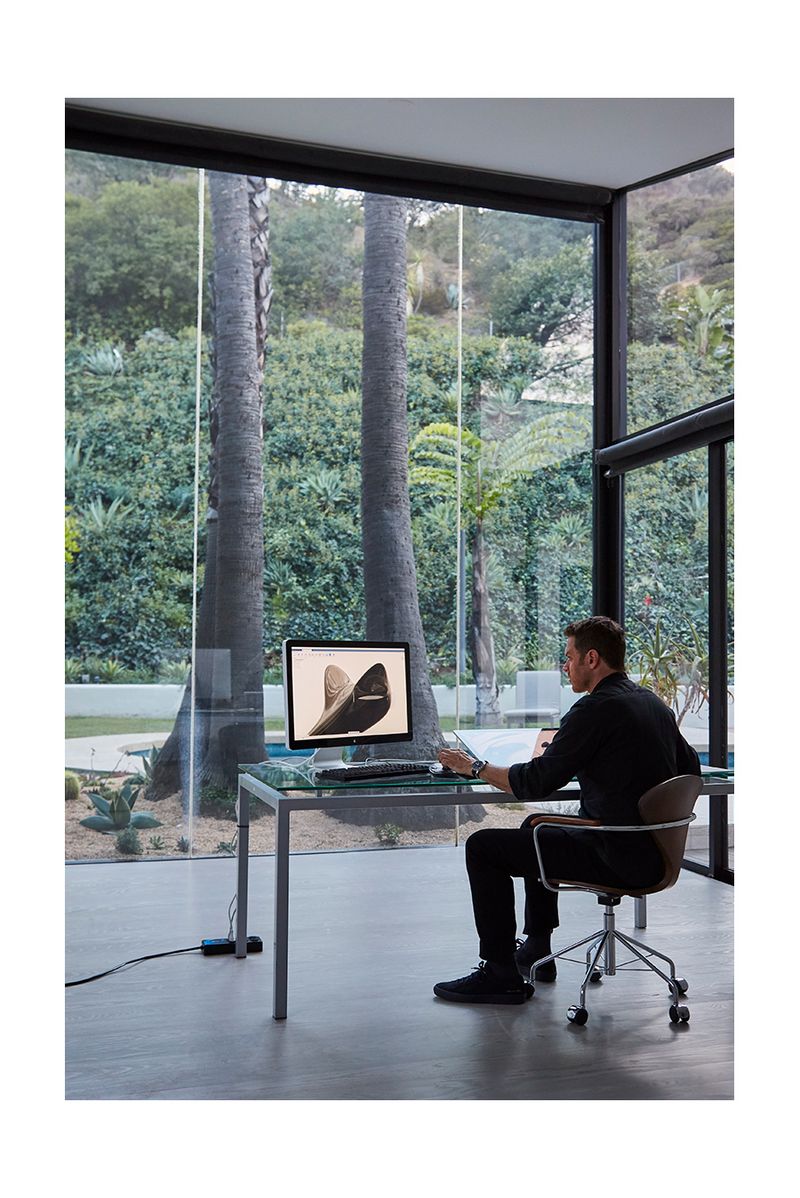

So, why now? The environment, he says, is an obvious concern, given recent legislative efforts to limit fuel emissions and, in some country’s cases, ban combustion engines outright. But bolstering his business’ eco-credentials is not his primary consideration. “Electric is largely about speed. It offers the raw tools to create the fastest machine on the planet.” For a designer who has spent the bulk of his career working with vintage parts, the move has meant going back to the drawing board in more ways than one. “Electric has a new set of parameters that need to be considered. Does it make sense to literally hand-hammer metal and a chassis or try to retro-fit a battery pack? My answer is no.” As a result, he’s needed to radically rethink every material and process (he mentions augmented reality and 3D scanning and sculpting as just some of the technologies he’s been experimenting with) as well as revolutionise his working practices.

He used to employ a small team, for example, but has made the decision to fly solo on this latest venture. “The paradigm of the motorcycle shop doesn’t work for this. I really need to shut that chapter… make it more intimate. Make it about me and pure imagination,” he says. Now he’s working alone, he takes the time every day to hike up into the hills above his home. “Los Angeles is like the ocean from up there. By the time I get back, my mind is clear and I’m ready to get to work.”

That need for autonomy is easily understood. Independence, after all, is why two-wheelers exist in the first place, and why the men who ride them will forever be fixed in our minds eye as wild ones in the mould of Messrs James Dean and Marlon Brando. Mr Barry still embraces that association: “Motorcycles are synonymous with this idea of rebellion. Doing things your own way,” he says. “And I can’t think of anything more rebellious than electric. It’s the most disruptive thing that we’ve seen in the 21st century.”