THE JOURNAL

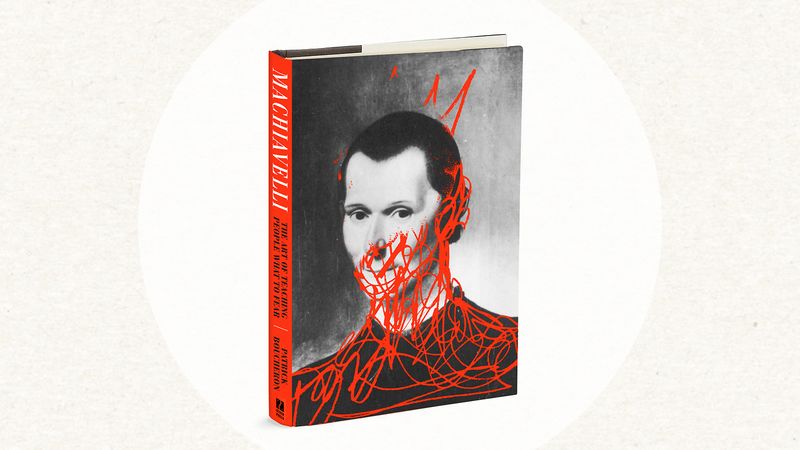

Machiavelli: The Art Of Teaching People What To Fear (Other Press) by Mr Patrick Boucheron. Image courtesy of Other Press

In 1975, political thinker Mr JGA Pocock published a book that seemed to define the contemporary mood. The Machiavellian Moment took the ideas of Renaissance Italy and transposed them to the new country that emerged out of the American Revolution. However, the parallels between this account of the embryonic US and the country at the time of Mr Pocock’s writing, ravaged by the fallout of the Vietnam conflict and the Watergate scandal, were obvious.

“American historians have since associated Machiavelli’s name with that form of political crisis,” argues Mr Patrick Boucheron, medieval historian and author of Machiavelli: The Art Of Teaching People What To Fear. “And today, we are undeniably living through another Machiavellian moment, again bringing the Florentine author close to the core of American reality.”

Despite spending much of his political career in lowly positions and then living in exile, 16th-century diplomat, philosopher, writer and historian Mr Niccolò Machiavelli’s reputation extends to the present day. The definition of a Renaissance man, working in numerous roles, his most influential work, The Prince, wasn’t published until five years after his death, in 1532. “Within 50 years of Machiavelli’s death, The Prince had taken its place on the Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books as a work of the devil,” says Mr Boucheron.

Mr Machiavelli’s name is now shorthand for a calculated, underhand form of politics. Indeed, Collins Dictionary defines “Machiavellian” as “cunning, amoral and opportunist”. But Mr Boucheron thinks that perhaps the word says more about his enemies’ attempts to discredit him than it does about the thoughts of the man himself. His book aims to “lift the mask of the monster”.

Mr Machiavelli’s ideas, or at least those attributed to him, often re-emerge in wider public discourse at specific times, Mr Pocock’s “Machiavellian moments”. “Interest in Machiavelli always revives in the course of history when the storm clouds are gathering, because he is a man to philosophise in heavy weather,” says Mr Boucheron. “If we’re reading him today, it means we should be worried. He’s back. Wake up.”

Here are four perhaps counterintuitive ideas drawn from the work of Mr Machiavelli that are just as relevant today.

01.

Aim low

Mr Machiavelli certainly knew an opportunity when it presented itself. The removal of Florentine friar Mr Girolamo Savonarola from high office in 1498 created such a power vacuum. But since Mr Machiavelli “had neither the birth, nor the education, nor the connections” to aspire to the lofty role of first chancellor, a position that had become vacant in the turmoil, he settled instead for a lowlier post, first secretary of the second chancery. “It was less well paid and less prestigious, but… more strategic – a discreet and influential position of responsibility.” Here, he was able to build a young and hungry team of loyalists around himself and “monitor the stew of opinions that was stirring up the common people”. The lesson: play the long game. And start at the bottom and work your way up.

02.

Do sweat the small stuff

Mr Machiavelli was fastidious, a quality he inherited from his father, a doctor of law, who methodically recorded all the incomings and outgoings of the family’s chaotic household. Mr Boucheron notes that the Machiavellis’ shared ambition “was focused on books, in the hope they might offer revenge, on the certainty that an opponent’s closely held weapons could be turned against him”. Above all, Mr Machiavelli Jr trusted raw data over opinions. “Men make mistakes in their overall judgments,” he noted, “but they don’t make mistakes about the details.”

03.

Stick to the rules

Mr Machiavelli saw law-making as conflict between a ruler’s desire to oppress the people and the people’s desire not to be oppressed by the ruler. Politics, then, becomes a game of give and take, and giving – granting the people greater freedom – perversely becomes a means of control. To restrict the people, likewise, can mean a regime ends up with less control. “What is most damaging to the public spirit, Machiavelli wrote, is ‘to make a law and not observe it, particularly when it is not observed by the person who devised it’.”

04.

Don’t have an end goal

“The ends justifies the means” is a phrase, often used in hindsight to excuse barbaric acts, that has long been associated with Mr Machiavelli. But, Mr Boucheron notes, “Machiavelli never wrote these words, nor would he have been capable of it. His philosophy of necessity rests on the principle of the changeableness of the times and the unpredictability of political action.” Mr Machiavelli was a man preoccupied with minute details, dealing with and adapting to the present, with a long-term objective of continuity and self-preservation. He had no interest in the end because “the end is still unknown. The end will always occur too late to justify the means of an action.”