THE JOURNAL

Mr Saul Bellow in Rome, Italy, September 1984. Photograph by Ms Marisa Rastellini/Mondadori Portfolio

The sartorial taste of the American-Canadian writer who penned one of the Great American Novels.

“I am an American, Chicago born… and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way.” So begins The Adventures Of Augie March by Mr Saul Bellow, published in 1953, and regarded by many, Mr Martin Amis, included, as the Great American Novel. “Search no further,” wrote Mr Amis in a later introduction to the book. “In these pages, the highest and the lowest mingle and hobnob in the vast democracy of Bellow’s prose.”

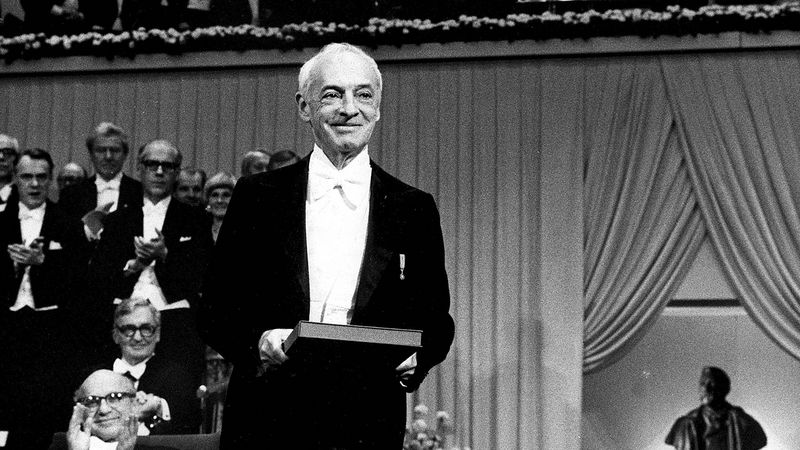

The novel, a turbo-charged Dickensian picaresque in which the footloose Augie, the child of Russian-Jewish immigrants, works his way out of the teeming slums of Depression-era Chicago via stints as a butler, shoe salesman and dog-groomer, among many others, announced Mr Bellow’s full flowering as a prose stylist of the first order – so much so that he would go on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1976. But Mr Bellow was also a virtuoso when it came to personal style, as evidenced by his Nobel acceptance outfit – an extravagant white-tie-and-tails ensemble that could give Mr Tom Ford lessons in the art of male luxe.

Mr Saul Bellow receives his Nobel Prize in Stockholm, 1976. Photograph by Globe Photos/Zuma Press

In fact, Mr Bellow was a supreme sartorialist before the word gained mainstream traction. A self-made man like his hero Augie, he knew the value of dressing well, both in terms of self-worth and the impression it made on others. When Augie starts work in an upmarket clothes store, clad in “tweeds and flannels, plaids, foulards, sports shoes, woven shoes Mexican style, and shirts and handkerchiefs,” he finds he can “talk firmly and knowingly to rich young girls, and to country-club sports students.” Mr Bellow took no less care in presenting himself, as his biographer Mr Zachary Leader recalled, on meeting him at a garden party in 1972: “It was a hot afternoon and some of the men were wearing shorts and Hawaiian shirts. Bellow, a dude, wore a brown silk suit and what I assumed was a Borsalino hat.”

It helped, of course, that Mr Bellow was street-smart handsome, in a hard-boiled kind of way. As Mr Amis recounts, after Mr Bellow’s first novel appeared, in 1944, he got a call from MGM: although he was too soulful-looking for a male lead, they explained, he could prosper as a character-actor type “who loses the girl to… George Raft or Errol Flynn.” Mr Bellow was happy to turn them down, but enlivened his own outfits with the kind of telling, borderline-theatrical details he loved anatomising in his characters: a rakish knitted tie and woven teardrop-shaped trilby worn with a black suit, for example, or a peak-lapel checked sports jacket with a white polo neck and felt homburg. The look was wise guy-academe, and Mr Bellow carried it off to perfection.

Saul Bellow in Paris, 1982. Photograph by Sipa Press/REX/Shutterstock

“Unexpected intrusions of beauty. This is what life is,” wrote Mr Bellow in his novel Herzog. Whether illuminating the struggles of those determined to survive against all odds, or donning a natty bow tie and grey suit in order to read the Sunday papers, Mr Bellow provided plenty, making the record in his own way.