THE JOURNAL

Mr Jonathan Majors speaks fast and low with a conspirator’s lean. He would make a marvellous Brutus, Mr William Shakespeare’s noble but conflicted assassin. A loose Texas twang kicks up when he is on a tangent, which is often. When we meet for coffee at a café in TriBeCa in New York, his eyes light up as the conversation turns to any of three topics: his idol, Mr Sidney Poitier; his nine-year-old daughter; or the poetry of Ms Mary Oliver.

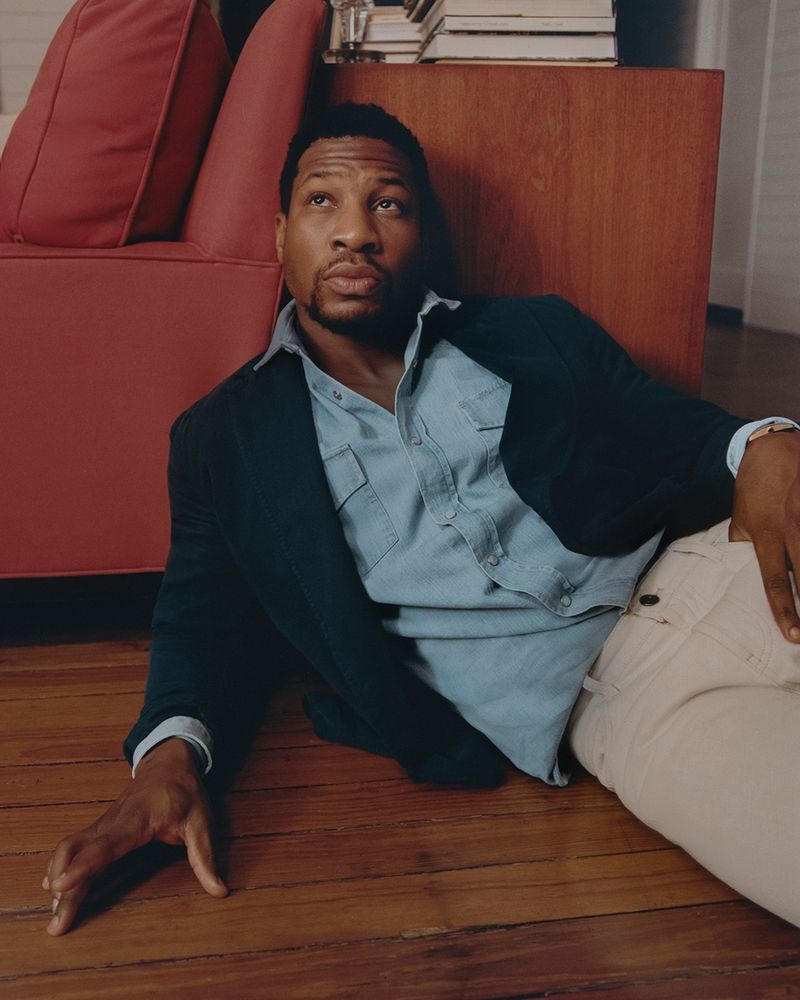

Majors’ handsomeness is both classic and bracingly new. The face of a man very much of this moment, on whom the most powerful film studio in the world has decided we should fix our gaze for the foreseeable future. He has three movies coming out in the first three months of this year. He is planning to publish a book of poetry. He has a wish list of performances he plans to bring to the stage soon. He is out of breath.

“Where was I?” Majors, 33, says more times than I can count. This meandering is understandable given the array of projects, current and in development, to which he is attached. We settle on his upcoming film Magazine Dreams, which premiered at Sundance, and is the first to be produced by his production company, Tall Street. Marvel’s Ant-Man And The Wasp: Quantumania follows in February and Creed III in March.

“It is the most intense prep I have ever done,” he says of playing an obsessive bodybuilder, in Magazine Dreams. Majors’ fanatical preparation for roles is well reported, so to hear him say this gives me pause. “There is a state of discomfort emotionally, which is my job as an actor. But as a bodybuilder, you are in a constant state of discomfort physically. Your brain starts to do things,” he says with a smile. One gets the sense he enjoys the torture of this self-imposed process; what it unleashes in his art. “Your body is screaming. You are ripping it apart.”

While filming it in Los Angeles, he ate six to eight meals a day and drank 850-calorie shakes in between. His character is consumed with getting his pro bodybuilding card. In the process he isolates himself and becomes violent, which is exacerbated by his steroid use.

“Then we layer in the fact that he is a young Black man,” Majors says. “Everyone has their trauma, everyone their history. The history that he is carrying is stupendous. That this man survives. But he uses all of that and he puts it in his body.” There is a beat where it’s unclear if he is talking about himself or the character.

Born in California and raised near Dallas, Texas since he was eight, he talks about his childhood there with a mix of distance and humour. His mother, a pastor, raised Majors along with his older sister and younger brother mostly alone. His extended family nearby had a farm on which he first became acquainted with horses, a skill that came in handy for the 2021 Netflix western The Harder They Fall. “You cannot lie on a horse.”

“I don’t know what my destination is… A lot of us are going short when we should be going long. Get down the field”

Growing up, his mother used to make him and his siblings recite the mantra “No drinking, no drugs, no sex” every time they left the house. “Even if your boys were there. ‘No drinking, no drugs, no sex. No drinking, no drugs, no sex. No drinking, no drugs, no sex’,” he repeats. “That would be a good title for the book of poetry I’m working on,” he adds, before pulling out a notebook and jotting down the line. “It will be a collection of 50 poems. Might get a little bit more. 50 is where we will start. They range from senior year of high school to this morning at the Ritz-Carlton.”

Majors digs out several leather-bound notebooks Mary Poppins-style from his duffel, a black TOM FORD. With each thwack of leather, he quells any disbelief in the earnestness of this lofty endeavour. He expects the book to be out in mid-2024. Two of his poems have already been published in The New Republic. His seriousness of purpose, be it for poetry, acting, or the simple act of ordering a quadruple espresso from a gobsmacked server, does not grate, but rather sweeps up any observer within its energetic dragnet.

His family experienced brief periods of homelessness growing up and he refers to himself as a juvenile delinquent. “I don’t know how I graduated high school, I was so truant,” he says. His Texas high school, massive and suburban, with one of the largest campuses in the country, was just the kind of place where a young man with an “authority problem”, as he describes it, could fall through the cracks, or worse. Theatre saved him. More specifically, two local acting teachers, Mr Jordan and Ms Keisha Williams, who pushed and prepared him to apply to drama schools. He went on to attend the University of North Carolina School of the Arts and graduated in 2012. After a short stint in New York, he did a master’s degree at Yale School of Drama.

The effort and expense of those early years still live with him. “My mother gave plasma,” he says of how she supported him at UNCSA as well as summer acting classes in Manhattan. He vowed not to come home until he “had a grip on something”, ie, had something to show for the sacrifice. He did not return home for 12 years.

“It was quite emotional when I finally did come back,” he says. “You want to make good, whatever that means.”

On his 30th birthday in September 2019, he had his Dallas homecoming. He had just filmed HBO’s Lovecraft Country, the sci-fi meets Jim Crow fantasia, for which he earnt an Emmy nomination in 2021.

“A ritual had concluded itself,” he says of his return, which inspired an entry for the forthcoming book. “The poem talks about her birthing me… And now I’m coming back to her now, to be birthed again or seen again, anew. Maybe there was a second birth in that 12 years away from her.”

Those years of sacrifice while away from home have not made him any less risk averse in his choices. His breakout role in 2019’s The Last Black Man In San Francisco, for which he was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award, could not have been further from the upcoming blockbusters. “Oh, I love the risk,” he says. “I love the smoke. I’ve got nothing to lose.”

Majors’ participation in the Marvel Universe began with Loki, the Disney+ series starring Mr Tom Hiddleston. It was his first appearance as Kang the Conqueror, a role he reprises in Ant-Man And The Wasp: Quantumania. He’s also signed on for Avengers: The Kang Dynasty, set for a 2025 release.

Despite the material and professional relief of sitting atop one of the most successful franchises, he still does not feel like he has “made it”.

“My last three pictures and my next picture were all directed by members of the African diaspora under 40. That’s not a coincidence”

“I don’t know what my destination is,” he says. “That is the mistake of our generation. A lot of us are going short when we should be going long. Get down the field. Just get down the field. And look up. If the ball comes and you catch it…” He trails off.

He recently caught up on theatre in New York – The Piano Lesson, Ain’t No Mo’, Death Of A Salesman, Topdog/Underdog. “Doing my due diligence, checking out the folks. Making sure everyone is punching up.” He has a Hamlet in him, he muses. The Seagull and A Raisin In The Sun are also on his dream list. The latter holds a special significance given its association with Sidney Poitier, who first played the role of Walter Lee Younger on stage and in the 1961 film.

“I hung his head shot up in my dormitory,” Majors says of the first Black man to win a Best Actor Oscar, who passed away last January, aged 94. “The way they put the Queen up. That is how I viewed him.”

At the Gotham Awards in December, Majors announced the Gotham Sidney Poitier Initiative, a mentorship programme aimed at supporting marginalised groups and helping them understand how the industry works. It has the backing of Apple and Google.

“There is a huge gap between what you think the business is as a Black person or a historically marginalised person, coming into the industry and what it really is,” Majors says. “They don’t teach that in drama school. You only learn how to survive the fray by getting in the fray. How do you get into the fray when there are gatekeepers actively keeping you out? [The Initiative] is not there to negotiate with the gatekeepers, but to knock the gatekeepers down.”

Majors describes his early years in show business as an exception that proves the rule. “I did quite well, establishing that type of mentorship early on,” he says. “The benefit I have is that I have a lot of allies. Casey Bloys [CEO of HBO], is an ally. Kevin Feige [president of Marvel] is an ally. John Lesher [producer]… These men have taken chances on me. White boys who invested in me as an artist.”

He is determined to spread that support around. “Where I get hung up is when I look at my contemporaries or those coming up. This is going to be a hard road, unless we partner with each other.”

Majors points to his collaboration with Mr Michael B Jordan, who directs him in the upcoming Creed III. “My last three pictures and my next picture were all directed by members of the African diaspora under 40. That’s not a coincidence, that’s by design. I did not decline work… Other folks just did not come to me.”

This approach mirrors that of Poitier, who would only appear in films that faithfully portrayed the Black experience. “Sidney made a way.”

Majors eyes widen when he talks about Poitier’s legacy. For the past few days, he has been fielding texts and calls from people who suddenly want to be a part of a project that it is getting some attention. He describes how “a big time Black executive” whose name he will not mention is asking to be a part of it after ignoring an earlier invitation. “This train is moving, you weren’t paying attention,” he says. “Sidney didn’t wait for anybody, we are on a mission.”

Majors’ next stop after New York is Atlanta, where he has a farm property and where his nine-year-old daughter, Ella, lives. “We like to shop together, read books. Road Dahl, A Series Of Unfortunate Events,” he says. “I have her memorise poetry.”

Whose poetry? “Mary Oliver,” he says. “She has a whole section about dogs. And my girl has her own dog, a cockapoo.”

Majors connects to Oliver’s reverence for the natural world. “She wrote outside,” he says. “Walking and travelling. I prefer to be outdoors. In nature or the opposite… Paris, Berlin, New York… just in it. LA. No middle ground. My life happens in extremes.”

He trails off, trying to think of a verse. “Only if you’ve seen angels…” He reaches into his duffel bag and pulls out a well-worn copy of the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet’s collection. The poem is “The World I Live In” and it contains the line “Only if there are angels in your head will you ever, possibly, see one.”

Majors says Oliver’s angels live inside his head alongside other less holy company. “I’m still angry. I still got that dawg in me that has something to prove. To the dad that left me, that acting teacher that said I wasn’t shit, the rich kids when I was growing up. As much meditation and prayer that I do… No one transcends…” He pauses. “Or, to be clear, I have not transcended that,” he says, the clear-eyed observation of someone skilled at examining their own inner depths.

“It could all end tomorrow,” he says, like a challenge to the gods. “Even with all of the faith, it could end tomorrow. Which makes it that much more beautiful. Every time you look at something… This is today. You know what I mean? Today I got the ball.”

And he is going long.

Ant-Man And The Wasp: Quantumania is out 17 February; Creed III is out 3 March