THE JOURNAL

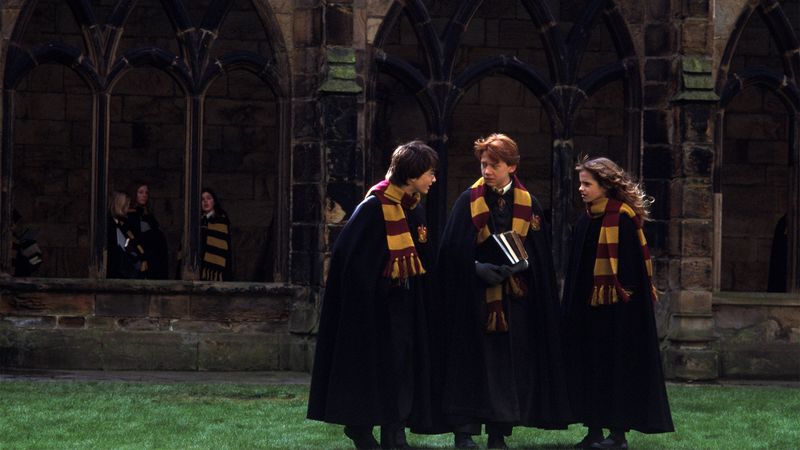

Mr Daniel Radcliffe, Mr Rupert Grint and Ms Emma Watson in “Harry Potter and the Chamber Of Secrets” (2002). Photograph by Warner Bros. Pictures/akg-images

Of all the disruptions and things that did – or didn’t – happen over the past year, by far the most significant change in my household was my son starting school. As milestones go, this was a big one. It wasn’t that long ago I was changing his nappy, now here he was, in his regulation jumper and tie, wearing proper shoes. Like a pair of his trousers, if you really were forward planning, there was a lot to take in.

Mr Olie Arnold, MR PORTER’s Style Director, tries to put into words how he felt when his son first went to school. “Proud, sad, happy,” he says, “a real mix as you realise it’s the start of an amazing journey for them and one that will shape their entire lives.”

Not to mention their wardrobes. “When I left school, I wanted nothing to do with ‘uniforms’,” Arnold says of his own education, but he admits that what he wore then has had a lasting impact on the way he dresses today. Sure, in the basic tenets that make up our outfits: shirts, trousers and shoes, maybe even a tie. Plus, how to maintain those items. And the colours: the navies, blacks and greys that, later on, men seem hardwired to wear.

For some of us, this sartorial default setting becomes an affectation in itself. From Mr Steve Jobs to Mr Andy Warhol to the Ramones, there are scores of stylish men who, in adulthood, have found their own uniform. A trademark look “potentially limits the amount of time and brain power in getting dressed,” Arnold says, “but those pieces have been picked because they form part of who you are and how you want people to perceive you.”

What you could call brand identity starts early. The focus of school, of course, is education. But even if it’s not explicitly in the syllabus, socialisation is a part of this. As well as phonics and times tables, my son is learning how to function within society. As such, the way he dresses plays a key role.

“There is a strong association between fashion and identity on a psychological, cognitive, emotional and behavioural level,” says Dr Ameerah Khadaroo, a lecturer in psychology at the University of the Arts London. After more than a year in flux, this takes on an even greater significance. “School uniforms can be used as an anchor to put children in the right mindset to resume their educational journey. This can boost their self-confidence, self-esteem, motivation and build positive peer relationships based on conformity rather than individuality.”

This last point is important, says Dr Michael C Reichert, author of How to Raise a Boy, published last year. By the time young boys start school, things are already complicated enough. “Research shows that beginning very early in their lives – Judy Chu (When Boys Become Boys) found by the age of four – boys respond to ubiquitous messages and pressures to fit themselves to a stereotype and everything changes,” Reichert says. “How they walk, talk, show their emotions, cuddle, the toys they play with, who they play with, etc. Research also shows how unhappy this inauthentic posture makes them, as an internal split develops between who they are, what they think and feel, and who the world knows them to be. A dissociation.”

Here, Reichert identifies what he calls “a fundamental, philosophical issue”: “Do we need to fit boys to a role or can we allow them, enable them even, to exercise their imaginations for who they want to be? More and more, younger generations of males are rejecting the cookie cutter, the predetermined identity, and claiming a right to flirt with alternative ways of defining themselves. But one unfortunate result, I fear, is an individualistic solution rather than a collective one – as if freedom is merely an individual right instead of a matter of social justice.”

“School uniform was initially introduced to provide clean, warm, decent clothes for the children at the school who, due to poverty, may arrive without appropriate clothing”

So, where does the school uniform fit in with this? Fittingly, it’s worth doing your homework. The first recorded use of a school uniform was at Christ’s Hospital in London, founded in 1552. As charity schools became more widespread, this dress code became the standard. “School uniform was initially introduced to provide clean, warm, decent clothes for the children at the school who, due to poverty, may arrive without appropriate clothing,” says Dr Kate Stephenson, author of A Cultural History of School Uniform.

But while improving pupils’ lot in life, Stephenson says that part of the move towards uniforms was to ensure that “charity-school children did not get above themselves. The coarse fabrics and blue colour of their uniform, a cheap dye and one often worn by servants, was also seen to inculcate humility and reinforce their lower-class status in life.”

What we think of as a school uniform today is more in line with what was later embraced by Britain’s elite schools. “[Uniforms] were initially introduced for sporting wear as games became increasingly important in public schools,” Stephenson says. “Sports uniforms served to prevent daywear from being ruined, as well as allowing teams to be distinguished from one another in competitive games. They were then gradually introduced into daywear – the most probable explanation is that the public schools were trying to separate themselves from the spate of new middle-class institutions that were popping up in imitation of them. The uniforms, once introduced, were also promoted as building community, providing a sense of belonging, helping with discipline and denoting hierarchy.”

Today, the focus is less on the “us vs them” and more on the “us”. A 2020 survey found “that three quarters of parents and 95 per cent of school leaders believe that a school-specific uniform helps to promote pride and belonging for a pupil in their school and local community,” says Mr Matthew Easter, co-chair of the Schoolwear Association. “A uniform is central to creating an egalitarian sense of pride and community across a school body, in much the same way that a sports team’s colours can bring a group of people together.”

These are exactly the reasons cited by the growing number of schools in the US now adopting a uniform – up over 10 per cent in the decade up to 2016. A “social leveller… liberating pupils from the pressure of looking or acting in a certain way” is Easter’s appraisal of the modern school uniform. “When children dress in a consistent way, there are fewer divisions and what to wear is one less thing for pupils and parents to worry about each morning. There are still a number of ways children have the ability to express themselves through the choice of bags, coat, shoes, or trainers, which is normally at the discretion of pupils and parents to choose according to their personal style.”

In my day, this meant trying to get away with murdered-out sneakers in place of shoes, but it takes a deeper significance within today’s changing notions of identity. “Gender identity is an increasingly important consideration with regards to school uniforms, and we are seeing schools and suppliers working closely to find solutions that can work for every pupil,” Easter says. “Every pupil should be able to attend school in a uniform that looks smart and helps them to feel comfortable.”

At its best, as the adverts for teaching courses would have it, school is about channelling raw potential, and uniform is seen as a tool toward this end. And even in adulthood, most of us are reaching for similar ideals – looking smart and feeling comfortable – when we get dressed each day. “Finding a look that works and repeating it is the easiest place to gain confidence and identity,” Arnold says. “There’s a perception that having a uniform means you cannot be an individual, but I don’t believe that. Whether it’s consciously or not, you always find the nuances to make it your own.”

A school uniform certainly hasn’t stopped my son from expressing himself. By the end of his first year, he was onto his second pair of shoes. His trousers had holes in the knees, or had been hacked into shorts. And, after some overzealous art classes, his shirts resembled a Mr Jackson Pollock canvas. He may have grown out of his clothes, but he’s growing into himself.