THE JOURNAL

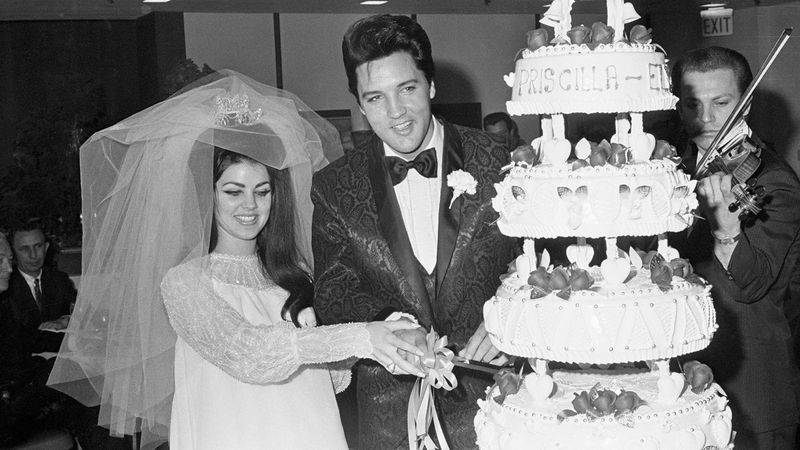

Mr Elvis Presley cuts the wedding cake with his bride Ms Priscilla Beaulieu at the Aladdin Hotel, Las Vegas, 1967. Photograph by Bettmann/Getty Images

Discussing the details of your death-row meal is – hopefully – a hypothetical pursuit for most. Yet while it might provide the non-condemned with carte blanche to indulge their wildest culinary fantasies, the actual requests of those awaiting the death penalty are often far more mundane.

According to Messrs Vincent Franklin and Alex Johnson, authors of the illuminating new book Menus That Made History, very few of those prisoners afforded a final meal opt for exotic and extravagant dishes, choosing instead high-fat, high-salt, high-sugar comfort food, with fried chicken coming top of the list. Trawling the archives of the American penal system, the authors go on to reveal the diversity of death-row dinner requests that vary from all-American classics and pints of ice cream to former Nazi officer Mr Adolf Eichmann, who asked for a bottle of wine from Israel’s Carmel winery, or the exacting Mr Victor Feguer, executed in 1963, who demanded a single olive with the pit in – the pit was later found in his jacket pocket. All of which are a world away from Jesus and his Apostles’ biblical Last Supper of unleavened bread and wine – a menu also explored later in the book.

Not all the menus explored by Messrs Franklin and Johnson are quite so macabre. Shining a spotlight on our mealtime preferences from the prehistoric – think woolly rhinoceros, waterlilies and tree bark – to the post-industrial, Menus That Made History charts our changing tastes and societal trends, and captures significant moments, from sporting successes to royal weddings, via the dishes served to our tables.

Their research takes in a variety of approaches, with some entries stemming from original copies of feted menus to others pieced together from accounts in diaries, instructions to kitchens and even studies into the dental plaque of ancient corpses. “We eat to survive and we eat to celebrate,” say Messrs Franklin and Johnson. “But this is not really a book about food – it’s about understanding what these culinary snapshots can tell us about certain times and places in our global history.”

Thus we’re invited on a journey to the summit of Mount Everest with Sir Edmund Hillary and Mr Sherpa Tenzing, whose necessity for easily digestible sugars and carbohydrates saw a menu of mint cake, dates, tinned apricots and sardines take precedence among the supplies on their successful expedition in 1953. More luxurious fare could be found on board Concorde’s maiden voyage in 1969, where fortunate diners could select from French chef Mr Paul Bocuse’s lavish menu that featured caviar and lobster canapés, fillet steak, Dom Perignon 1969 champagne and Havana cigars (smoking was not banned on Concorde until 1997).

Expensive tastes could also be found on board the RMS Titanic. Yet although 1,500 passengers met the same tragic end in 1912, the menus served aboard the doomed cruise liner revealed a titanic gulf in diet according to the ticket held by passengers. While first-class guests enjoyed the kind of opulence the Edwardians are renowned for, with oysters, foie gras and filet mignon among 11 courses served on the night of the disaster, below deck, third-class passengers were doled out “cabin biscuits”, an almost indestructible mixture of flour, water, salt and fat – and a seafarer’s staple since the Crusades.

Going some way to bridge the class divide in the UK was the 1944 Education Act, which made it compulsory for education authorities to offer school dinners, which were free for pupils who couldn’t afford to pay. This game-changing policy by Mr Rab Butler was intended to tackle malnutrition by providing one third of a child’s daily nutritional needs. By 1951, nearly half of Britain’s schoolchildren were being served school dinners featuring simple dishes such as stewed steak, mashed potato and Bakewell tart that evoke nostalgia to this day.

Elsewhere Messrs Franklin and Johnson explore the myths surrounding another national institution, highlighting the 17th-century Jewish refugees from Portugal and Spain who introduced Britain to fish fried in flour and the French and Belgian Huguenots, arriving shortly after, who brought with them fried potatoes in the form of frites. As the authors go on to explain, what the British did, to genius effect, was pair the two together.

With each menu revealing something unexpected about its context, Menus That Made History encourages us to look beyond simply what we’re eating and consider things that are far more significant than the meal itself.

Menus that made history by Vincent Franklin and Alex Johnson. Image Courtesy of Octopus Books