THE JOURNAL

Clockwise from top: “Rex” peeler by Zena, 1947; traditional “Lancashire” peeler, “Aussie” peeler by Dalsonware, 1947. All photographs by Ms Sarah Hogan, courtesy of Quadrille

Farmhouse Aga set-up or swish minimalist marvel? Why the contemporary kitchen often favours form over function.

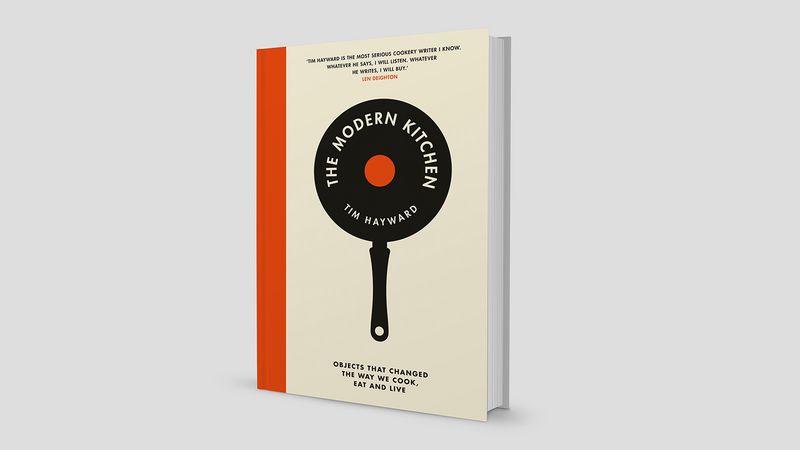

In researching my new book The Modern Kitchen, I must have looked at thousands of images, hundreds of drawings and plans and read dozens of articles about “The Dream Kitchen”. That term in itself is fascinating. I don’t believe we “dream” about efficient workplaces, we dream about aspirations, hopes, fears and secret desires. It’s a testament to how important the kitchen has become as a consumer object of desire that we are ever enjoined to “dream” about it. In 1977, when the cookery writer Ms Elizabeth David was asked to write an essay on her fantasy kitchen, she specified an airy, well lit, uncluttered space “more like a painter’s studio furnished with cooking equipment than anything conventionally accepted as a kitchen”, which will come as something of a surprise to the thousands of cooks who’ve set up their own kitchens in what they imagine is her style – a stripped pine table, a Welsh dresser and, set like an altar on a reinforced floor, a mighty Aga.

Most highly designed built-in kitchens either refer visually to an ideal in a Victorian stately home or farmhouse or some kind of uber-efficient futuristic laboratory. We aspire to counters of marble or polished acreages of surgical stainless steel. We talk about the kitchen as a social space, a warm “heart of the home”, even though it usually hosts family members flitting in and out, quickly grabbing snacks. In the Modern Kitchen, form very rarely follows function.

Left: Original Bialetti “Moka Express”, circa 1933. Right: two vintage garlic presses

Oddly, I think, my fantasy kitchen should be small. In 1926, Ms Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, an Austrian architect, designed the first standard “fitted” kitchen for a giant social housing project in Frankfurt. In preparation for the work, she’d spent time in the kitchens of ocean liners and Pullman trains, she’d imbued herself with the “time and motion” research that was sweeping through contemporary industry and she realised that the ideal domestic kitchen is like a “station” in a professional one – anything outside the arm span of the individual operating it means extra labour in moving about. “Light, airy and large” seem part of the tendency towards social kitchens. To be brutally honest, I don’t like too many people being in my space while I’m cooking and the idea of the kids doing homework on the kitchen table and a dog reclining on a sofa somewhere in sight of the hob just fills me with profoundly misanthropic thoughts.

I’ve become a complete swivel-eyed zealot for the magic of induction hobs. The ability to slave over what’s effectively a “cold stove” has transformed the Modern Kitchen and I find its controllability is excellent for even the most arcane and arty processes. I demand, of course, a vast magnetic rack for an absurd collection of knives, but I’d also like to keep pots hanging high and out of the way. A clean and open station is everything.

It seems an inexplicable quirk of Britishness that we organise our kitchens along the walls – which means that, no matter what task you’re performing, you’re facing a wall and blocking your own working light. I have a fantastic bench in the middle of my own kitchen, around which I can move easily. It’s a 1958 Allen & Hanburys operating table that I rescued from a skip, topped with a big slab of butcher block. It weighs just short of half a tonne, but it glides around the room on casters and rises and falls magically at the touch of a foot pedal. OK, I agree it’s ridiculously overspec, but I still reckon a kitchen needs a “bench”. Something substantial enough for a bit of butchery if the occasion arises, but suitable, with a few high stools, for informal eating.

Left: Anova Precision Cooker used to create the sous-vide cooking technique. Right: Iittala Sarpaneva casserole dish, by Mr Timo Sarpaneva, 1960

Equipment in the kitchen is a vexed question. Like most writers, I pretend to be scornful of “gadgets” – but this really just means that I try them all and am just more merciless than most in triaging them. In truth, there are some ridiculous tools I couldn’t bear to be without. I have my nan’s old spring whisk, a tiny little thing that has, so far, guaranteed I never split a sauce or mayonnaise; I have a rotary hand whisk that has no other purpose than removing the stringy bits from eggs to which my family is unaccountably averse. I have an incredibly poncey “sous-vide” kit that I only use to make the most amazing slow-cooked stews. I may have a garlic press – though obviously, I’d never admit it. And, for no reason I can adequately explain, I will not allow a colander. I know. It’s a weird thing and runs deep. My most important “gadget” is probably the simplest – six dessert spoons, their handles drilled for hanging on a hook next to the cooker, and stamped “NAAFI”. These hoary old mess-hall specials are always at hand for tasting everything.

I suppose my own kitchen evolved to fit me as beautifully and personally as a bespoke suit – or I suppose as Ms Elizabeth David would have preferred – an artist’s studio. It’s difficult to imagine a fantasy that could ever spring into being fully formed. I think, perhaps, what would really improve the dream would be the outlook. Move my kitchen to Case Study House #22, the Modernist glass box in the Hollywood Hills, overlooking LA, designed by Mr Pierre Koenig. Imagine cooking in that room, with that view… I’d almost not notice the occasional colander.