THE JOURNAL

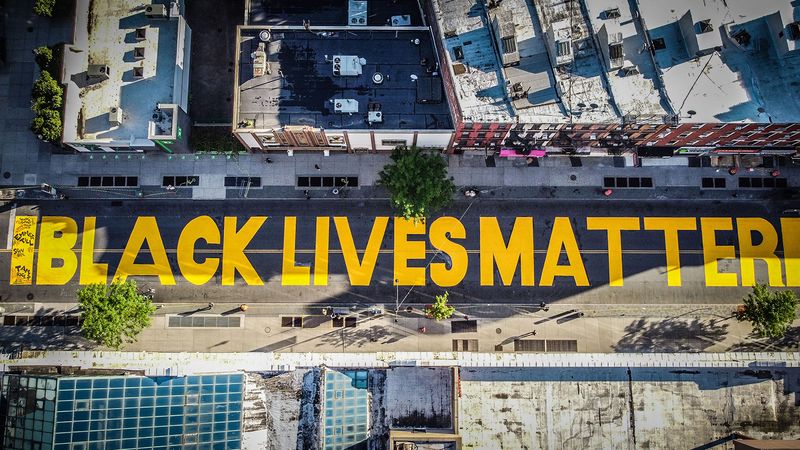

Black Lives Matter mural, New York, June 2020. Photograph by Zuma Press/Eyevine

What does it mean, to be black in the world today? Op-eds, playlists and documentaries curated throughout October have sought to unpick the answer in recognition of the month that has marked Black History in the British calendar since 1987. As we move on to the month of growing moustaches, it’s worth remembering that, in the same way black history doesn’t cease to have relevance once 1 November rolls around, so questions of racial justice do not fold neatly into convenient timelines. The history of blackness bears witness to the fact that this is a long, emotionally ambiguous grind. The recent acquittal of the officers who shot Ms Breonna Taylor, with no more than a reprimand for the damage done to her neighbour’s wall, emphasises this.

Still, there are signs of hope, underpinned by the extraordinary arc of events that has unfolded between last year’s Black History Month and this. In fact, in many ways 2020 has been a pivotal year for issues of race and justice, or at least in terms of how we talk about race and justice. That’s why we’ve put together a roundup of some of the most salient moments of the year, so that we can reflect, learn and, hopefully, progress.

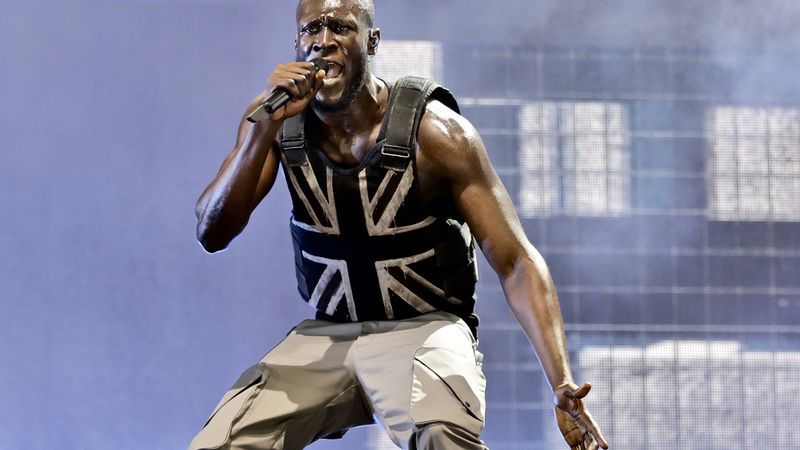

01. Stormzy and Mr Piers Morgan

Stormzy on stage at Glastonbury Festival, June 2019. Photograph by Retna/Avalon.red

Six months after Stormzy became the first solo black Briton to headline Glastonbury, wearing a Union Jack-emblazoned stab vest, no less, a miffed Mr Piers Morgan took to Twitter to attack the grime star for some new perceived indiscretion. Stormzy had called the British prime minister Mr Boris Johnson “a very, very bad man” during a Q&A session with children from his old primary school. “He shouldn’t have done this, and he shouldn’t have been allowed to do this,” Mr Morgan tweeted. A typical first salvo in the dog-whistle tactics employed by established voices to suppress those who challenge the status quo. Stormzy’s response? An equanimous “lol” that made it clear he was holding his ground. And that the default reaction to “old power’s” opprobrium did not have to be to kowtow.

02. Black vs “all”

This may be the first year since Mr Ansel Wong, Ms Linda Bellos and Mr Akyaaba Addai-Sebo started Black History Month in the UK that the contrary gripe “all history matters” has been muted. Confined by Covid-19, we were captive witnesses as instances of police brutality were streamed over social media. What we saw revealed the true dynamic between the rallying cry used by the Black Lives Matter movement since its inception in 2013, and the suffocating response, “all lives matter”, deployed by detractors to confuse and diffuse the campaign. As Mr George Floyd struggled to breathe for eight minutes and 46 seconds beneath the knee of police officer Mr Derek Chauvin, 2020 showed us that, in fact, all lives do not matter.

03. The redemption of Mr Colin Kaepernick

Messrs Eric Reid, Colin Kaepernick and Eli Harold before the game between the San Francisco 49ers and the Seattle Seahawks at CenturyLink Field, Seattle, September 2016. Photograph by Mr Joe Nicholson/USA Today/PA Images

When former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Mr Colin Kaepernick started taking the knee to protest police brutality in 2016, he received condemnation, death threats and the moniker “son of a bitch” from President Trump. When he opted out of the final year of his 49ers contract to find a new team as a free agent, Mr Kaepernick wasn’t signed by any team. A talented sportsman by any measure (he previously led his team to the Super Bowl), yet he hasn’t played since. By the time Nike made him the face of its 2018 campaign – with the slogan “Believe in something. Even if it means sacrificing everything” – the NFL had banned players from kneeling during the anthem. Meanwhile, an enraged President Trump said Nike was sending a “terrible message”, triggering his supporters to burn their (already purchased) Nikes.

And then came spring 2020. Protests against the killings of Mr Ahmaud Arbery, Mr George Floyd and Ms Breonna Taylor began with people taking the knee in Minneapolis. The practice soon spread across cities, states and nations. And this June, two years and a month after NFL commissioner Mr Roger Goodell banned players from protests in the style of Mr Kaepernick, he issued an apology.

Tweeting under the hashtag #InspireChange, Mr Goodell said: “We, the NFL, admit we were wrong…” Then went further, saying: “The protests around the country are emblematic of the centuries of silence, inequality and oppression of black players, coaches, fans and staff.”

04. The castigation of Meghan, Duchess of Sussex

There really are no such things as fairy tales. Just ask the Duchess of Sussex, Ms Meghan Markle. A biracial woman who fell in love with a prince, married into his family, but refused to dance to the British media’s tune. Barely hidden in the treatment of Ms Markle is the very real practice of misogynoir: the vilification of black women that belittles them for everything from their hair, to being “angry”, the “mammy complex”, over-sexualisation and – Ms Markle’s main crime – being “uppity”.

Recognising the insidious nature of this behaviour, Ms Markle has created her own narrative. One that has taken the couple away from the UK and the royal family and, more recently, saw her husband, Prince Harry, join her for an interview with the Evening Standard to celebrate “NextGen trailblazers in the black community” for this Black History Month.

05. Protesting in a pandemic

A protester faces police in riot gear during a march on the Arizona State Capitol, Phoenix, May 2020. Photograph by Mr Rob Schumacher/The Republic via USA Today/PA Images

The current wave of the Black Lives Matter movement started on 26 May 2020. The day before, Mr George Floyd, a 46-year-old African-American man, was killed, pinned to the ground by a knee to the neck by a white police officer. In the weeks and months that followed, protests against police brutality and systemic racism spread to more than 150 cities in the US, and worldwide, from Sweden to Australia and across the UK. What marks these as different from the first wave of protests, sparked by Mr George Zimmerman’s 2013 acquittal for the shooting death of Mr Trayvon Martin (a 17-year-old walking home through an area where he didn’t live) is the allyship across race, class and cultures. The call to address the inequality blighting black lives is coming from a mix of voices, demonstrating the intersectional activism that a truly equal society requires.

06. Adele, Bantu knots and cultural appropriation

August Bank Holiday is synonymous with the Notting Hill Carnival. Forced to go virtual by the pandemic, the community and its supporters took their revelry online. Among those partying was singer Adele, who posted a photo of her sporting a Jamaica-flag bikini and a Bantu knot hairstyle. It caused a social media storm, with debate raging over whether Adele wearing her hair in the traditionally afro hairstyle was cultural appropriation. At the root of the issue with cultural appropriation is the fact that black cultural traits that are routinely reviled when seen on a black person become desirable on a white person (Ms Kim Kardashian West is seen as a frequent offender). The offence cuts deeper when the white person taking on the trait benefits financially. So, what of Adele? Here, I will speak personally because opinion is truly split. For me, it was appreciation not appropriation. It’s Adele. She grew up in Tottenham in north London. It was Carnival. Enough said.

07. The toppling of old idols

“A Surge of Power (Jen Reid)” by Mr Marc Quinn, Bristol, July 2020. Photograph courtesy of Marc Quinn Studio

As Black Lives Matter protesters took to Britain’s streets in June, a reckoning with the country’s own history of racism, rooted in the practice of slavery, unfolded. Attention turned to statues erected to venerate Britons considered great by the established view of history, but who were profiteers from the slave trade. In Bristol, demonstrators pulled down the bronze statue of slaver Mr Edward Colston and tipped it into the harbour. An unwelcome move for traditionalists, but it has kickstarted debate around who we uphold as good citizens. A point creatively made by artist Mr Marc Quinn with his sculpture of protester Ms Jen Reid, who was part of the crowd that removed Mr Colston’s statue. Modelling her in black resin and steel with her fist raised, Mr Quinn erected his statue, named “A Surge of Power (Jen Reid)”, in secret, placing it on the plinth where Mr Colston’s bronze figure had stood a month earlier.

08. Say Her Name. Still. Ms Breonna Taylor

On 23 September, the three officers who executed the no-knock search of Ms Breonna Taylor’s apartment that ended with her being shot at least five times were acquitted of all charges relating to her death. Taking to social media to express dismay at the grand jury’s ruling, people around the world posted a split-screen image of Ms Taylor with Mr Emmett Till, the 14-year-old African-American boy lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of wolf-whistling at a white woman. When Mr Till’s mother, Ms Mamie Till, saw her son’s brutalised body, she chose an open casket so others could witness the horror of what had happened to her child. Thousands attended his funeral and Jet magazine published the image of Mr Till’s broken body. Yet on 23 September 1955, his two killers were acquitted.

Just as Mr Till’s killers later characterised him as an aggressor, Ms Breonna Taylor’s character has been called into question, with whispers that insinuate her actions and lifestyle somehow made her complicit in the botched police operation. But some things have changed since 1955. After the hearing, a grand juror anonymously requested that the transcripts from the hearing be released for public scrutiny “so the truth may prevail”. The court has agreed, and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund is conducting its own review of the proceedings.

After all of this, are we in a better place? Covid-19 has proved more deadly to people of colour, a likely result of health and economic inequalities. Meanwhile, the release of Mr George Floyd’s killer in September on $1m bail raised by his supporters suggests there is a long way to go. Social justice requires political change. But the galvanising of the grassroots signals hope. Hope in the allegiances forged protesting in the streets. Hope in the frank conversations being had about white privilege and how to tackle it. And hope in the collective awakening to the mechanics of oppression and how we can challenge them. And running parallel to the stories of loss and discrimination are stories of innovation, resilience, resistance, honour, love and creativity. That is the history of blackness.