THE JOURNAL

The year is 2002 and_ Dallas_ star Mr Larry Hagman is sitting on a panel of what appears to be a quiz show. Two hosts, Messrs Vic Reeves and Bob Mortimer, enter the studio, limbs flailing wildly. Hagman is greeted by another man, this one dressed as middle-aged a woman, whose name is Marjorie Dawes. He must answer questions produced from the buttocks of a toy sports car. “True or false: when a cat miaows, it is actually saying ‘get me out,’ as it is actually a rabbit trapped in a cat’s body?” He looks bewildered. A newspaper TV reviewer described Hagman’s appearance on surreal British quiz show Shooting Stars as “like a man in a nightmare”. But he was not in a nightmare at all – he had just unwittingly entered the surreal dreamworld of a Yorkshireman named Mr Jim Moir.

If you were born in the UK before the 1990s and you or your parents had a taste for the absurd, you can probably quote catchphrases from Shooting Stars. Created by Moir (the real-life human) and starring Vic Reeves (his comedy creation) alongside his partner-in-silliness Mr Bob Mortimer, the show ran on the BBC from 1993 to 2011 attracting more than five million viewers at its peak. “Vic and Bob” became British comedy legends and national treasures.

Moir’s anarchic whimsy was first unleashed on the British public in 1990 with his TV debut Big Night Out. As Vic Reeves, he helmed a mock variety show that featured a dizzying array of hilarious and chaotic set-pieces (perhaps it’s best if you watch it for yourself). And before that, even, came the art project that birthed his stage name, and which in turn developed into a character with a life and fame of its own that, ultimately, not even Moir could control.

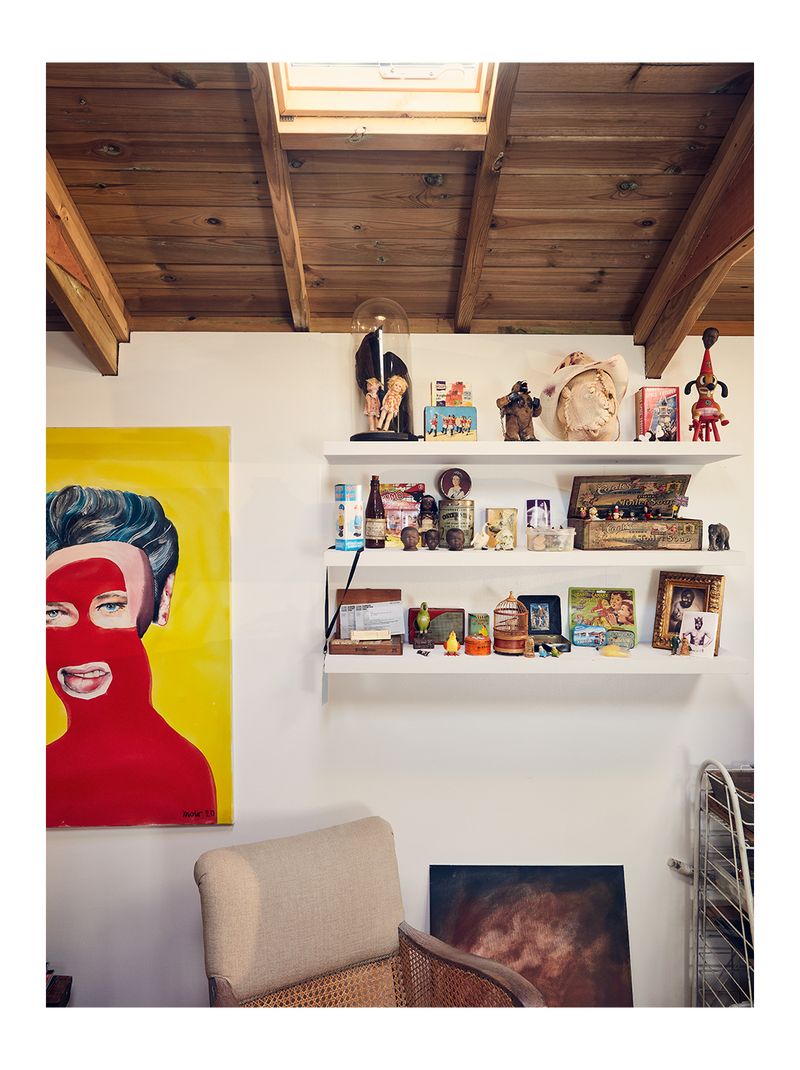

Even his biggest fans might be surprised to learn, then, that Moir considers himself to be a painter, principally. If you take a look at his Instagram page, you will see delicate, skilled watercolours of ducks, rhinos and birds. Leaf through Vic Reeves Art Book, released in October last year, and you will get a sense of the more bizarre and eclectic nature of his unique brand of art, from grotesque self-portraits, to a surreal pencil drawing of the Beatles and an oil painting of a naked Sir Elton John.

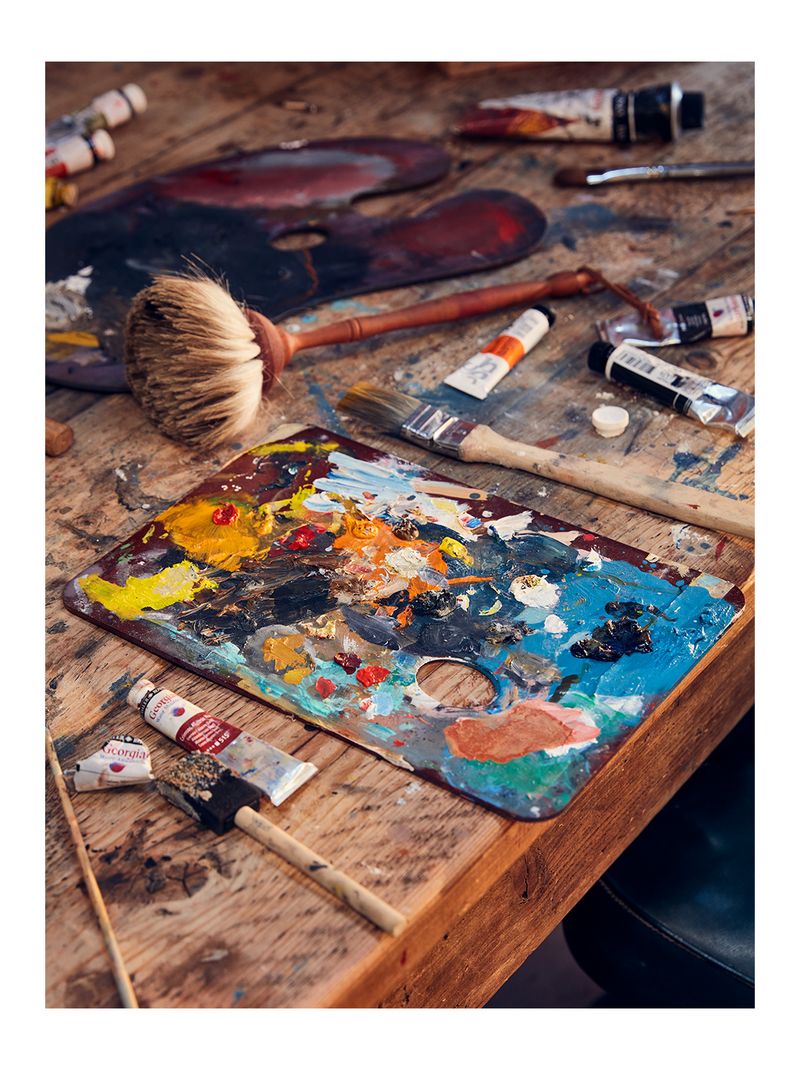

It is art rather than comedy (although the two are definitely blurred in Moir’s world) that brings MR PORTER to his house in Kent for a shoot in his garden studio – where he spends most of his time these days. Moir is modelling shirts bearing artwork he offered to Mr Stevie Anderson, owner of Endless Joy, for a collection now exclusively available on MR PORTER. Anderson, who is a huge of fan of Moir, considers Endless Joy to be more of an art project than a fashion brand, so for him it was a natural partnership. Net profits from the collaboration will benefit MR PORTER’s Health In Mind fund.

“Art comes first,” Moir says. “Always.” And, he is keen to stress, it was always so. “Whatever you become famous for, that’s what’s going to stick in people’s minds. People will think I’m a comedian. Even though, the first thing I ever did was be a painter. Going on TV was a second option, a day job. I’m always going to be secondly a painter. There’s nothing I can do about it.”

The truncated story of how Reeves came to be goes like this: after attending art school in south London in the early 1980s, Moir got a job booking acts at a comedy club. Instead of paying anyone to perform, he pocketed the cash and came up with material for a solo performance to last an entire evening. (This is how he met Mortimer, a solicitor in the audience who he brought up on stage.) Moir talks fondly about making cardboard props in his Deptford kitchen, which he would then take down to the pub in a wheelbarrow.

A far cry from the paintings that he does today, but were these nights an early manifestation of Big Night Out? “Yes,” he says immediately. “But it was seen as end of the pier comedy… When I was at art school, I loved Gilbert & George [the collaborative art duo], so Big Night Out was me trying to do a Gilbert & George. I really liked their films of them getting drunk on gin and doing the ‘Living Sculptures’, singing ‘Underneath The Arches’. I was kind of just doing that – performance art. That’s what I thought it was anyway.”

But before the performances, he happily tells us, he enjoyed good old-fashioned painting. “My first exhibition was in 1984 and I was doing copies of [Mr Jacques-Louis] David and Caravaggio, selling them really cheaply, for about 40 quid,” says Moir. “They’re somewhere hanging on someone’s wall, I guess.”

Vic Reeves continues to be a fixture on British screens – recent appearances on Netflix’s The Big Flower Fight and Channel 4’s Gogglebox attest to that. Despite this, Moir tells us that he makes more money as a painter than he ever did on TV. His art now sells for thousands of pounds, and his work is increasing in value. A review of an exhibition at St James’ Grosvenor gallery early last year described his paintings – from portraits of Mr Elvis Presley to grotesque and pastoral scenes – as “Boucher meets Basquiat”. The Dada art movement is mentioned in most artist biographies and press releases for his work. Formed in Zürich over a century ago, the nonsensical and satirical art, poetry and performances seem like the perfect fit for Moir, not to mention the fact he fronted a BBC documentary on the topic. If Mr Marcel Duchamp didn’t sign a toilet and pronounce it as art, Jim (or Vic) almost certainly would have. Live on television. While wearing cardboard teeth.

“I think Dada’s a bit contrived,” Moir notes. “I like to feel that what I do is more natural. People are always trying to put a label on everything. I suppose if they want to use Dada and surrealist for me, that’s as near as they’re going to get.”

Most commentators see Dadaism as a response to the ravages of WWI, although Moir disagrees. “[It was just] cheekiness and confusion,” he says. This sounds like him all over. “I know what you’re saying. I had a cauliflower in a fish tank [during Big Night Out] and said it was a stand-up comedian,” he says, laughing. “I used a vocoder to record some really awful jokes and let people look at the cauliflower for 10 minutes.”

It is this life-affirming belief in mischief making that seems to animate Moir. He gets up out of his chair to act out the memory of when he and Bob got into “the most trouble” filming a sketch for Shooting Stars. “We had a stuffed buzzard [with] a crucifix around its neck. I said it was a Christian and all the Christians complained. ‘Birds cannot be Christians!’” he says, adopting an indignant tone.

He is nostalgic for a time when you could get away with more. Before Big Night Out got snapped up by Channel 4, buzz around his first pub shows spread by word of mouth (eventually attracting the likes of TV personalities Messrs Jools Holland and Jonathan Ross), something he now compares to how rave culture proliferated. “What was good about Britain in the 1980s was that it was still that punk aesthetic – have a punt on it, if it’s different, it’s good,” he says. “So, let people do what they want to do, and also do it quickly so you don’t lose the impetus and excitement. Nowadays, you wouldn’t be allowed to do it.”

Perhaps his paintings are his way of doing something anarchic, on his own terms, free from compliance forms and hang-wringing TV producers. But for a man who clearly has a feverishly active mind, he must get lonely in this solo practice. “No, I just love being at home and working up there,” he says, gesturing to his studio. “I’m quite happy to do that forever. My mind is enough for myself.”

It’s tricky to work out whether Jim uses art as a soothing, meditative practice, or simply as a medium through which to channel his ideas. “It’s both, really,” he says. “It’s a purging. It gives me a kick. At the end of the day, you look at something and think, ‘I’ve done that, it’s brilliant. I like that.’ Or, ‘That’s rubbish.’ Usually, I’ll keep going until there’s something I’m happy with.”

Being indoors for the best part of a year has increased Moir’s artistic output. He has found time to produce a podcast with Holland, which is loosely, like anything with Moir, based around transport. He is also working on a film with Mortimer called The Glove. Its production has been delayed by Covid and various other hiccups, and, apparently, Mr Damien Hirst offered to finance it at one stage. Can he give a brief synopsis? “It’s the Holy Grail told from modern times where the Grail is Michael Jackson’s glove.”

Before he stops the interview for lunch, conversation leads to life after the pandemic. Despite his slight disdain for Dadaism, Moir seems to support a similar kind of reactive absurdist uprising of nonsense – a revolt against boredom, bureaucracy and statistics.

“Before this, people were getting really serious – there was a real earnestness going around. I think there’s got to be a turn. People are going to have to start wanting something a bit more ridiculous in their lives.” And if Jim (or Vic) were to lead this, what might it look like? “I dunno,” he says, after pausing for thought. “Just follow what I’ve been doing all these years and take your pick.”