THE JOURNAL

View over rooftops in Marrakech. Photograph by Mr Adrian Morris

How the North African kingdom became a home from home for the editor-in-chief of Another Man.

I was nine years old and suddenly surrounded by drumming tribes, blind beggars and monkeys on chains. It was dizzying, biblical, like nothing I had ever seen before – except maybe in Raiders Of The Lost Ark. This was Marrakech and I absolutely loved it.

We had gone on a family holiday in search of winter sun. My twin brother spent the entire trip in his room (well, doubled-up in the bathroom, to be frank) and my sister was traumatised by the sensory overload of cobra charmers and overzealous merchants. Neither my siblings nor parents have returned since. I, on the other hand, have returned again and again, three or four times a year, to revel in the drama of the place.

I’ve climbed the Atlas Mountains and slept in the Sahara, ridden camels and death-trap calashes, swum in choppy Atlantic waves and palm-shaded pools, dined in palaces and danced till dawn with creatures of the night, been scrubbed and massaged within an inch of my life and got lost down more side streets than I care to remember. All the while, devouring tales of what led so many fascinating people to this wondrous place: writers Messrs Paul Bowles and William S Burroughs; Mr Brian Jones and The Stones; interior designers Mr Bill Willis and Mr Christopher Gibbs; Mr Paul and Ms Talitha Getty; and, of course, the ultimate poster boys of Moroccan chic, Messrs Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé.

Before she met me, my wife Anna-Marie had also spent her adult life exploring Morocco, from Fez and Essaouira to Chefchaouen to Tangier. But it is always Marrakech we hunger for. Since my first visit back in the mid-1980s, the city has changed immeasurably (they are paving the souks as I write this). Thankfully, in its drive to modernise, it’s lost none of its charm, elegance and total WTF-ness.

What follows, then, is not a list of my top restaurant recommendations or places to stay. Rather, very personal memories and moments of Morocco, fragments that whisper to me in the London night, beckoning me back.

Lost property

Riad Madani, the 19th-century property in the labyrinthine heart of Marrakech’s Medina has one of the largest residential gardens in the city. It was – and, for someone else, still is – the most magical place in the world. It was our home from home: we always stayed in the same Oriental Suite, and grew to know the owners and staff. It was bliss; intoxicating for the senses and nourishing for the soul, decorated in cracked portraits and original works by Messrs Pablo Picasso, Julian Schnabel and Andy Warhol. We introduced friends to this hidden oasis: we even celebrated a wedding there. And then the ailing owner sold it. Today, it is a private home – renamed and renovated – and the magnificent Madani, with all our memories, has vanished like a mirage in the heat.

Recommended reading

I read Let It Come Down by Mr Paul Bowles on my most recent excursion to Tangier. It’s a disturbing tale of colonial decay, backroom dealings, sweaty trysts and super-strength hallucinations. The following quote stuck with me; it seemed to tap into a feeling I’ve experienced many times in Morocco, and perhaps explains why, like a moth to a flame, I keep returning. Here it is: “That was what he wanted, to be baked dry and hard, to feel the vaporous worries evaporating one by one, to know finally that all the damp little doubts and hesitations that covered the floor of his being were curling up and expiring in the great furnace-blast of the sun.”

Stop and listen

From the famous blue of Mr Saint Laurent’s Jardin Majorelle to the indigo walls of Chefchaouen, people talk a lot about the colours of Morocco. And with good reason: the palette is remarkable and vivid. But, for me, it’s the sounds that linger, that often stop me in my tracks, demanding to be savoured. Mr Paul Bowles travelled extensively recording the traditional Berber, Arabic, Andalusian and Jewish music. And it was the Joujouka musicians that drew Mr Brian Jones over in 1968. (In Essaouira, I first heard a strange genre that I can only describe as Berber-techno-reggae.) It is not simply the music, however. No, it’s the ordinary sounds that I take away. The birds feverishly chirping in the morning, among the cascading bougainvillea, and as they jostle for their beds at dusk. The call to prayer, blasting out across rooftops and trees, instantly rooting you in time and space. Mr Bowles wrote about the sounds of footsteps in Fez: there is something about the way sound travels here, reaching you unencumbered.

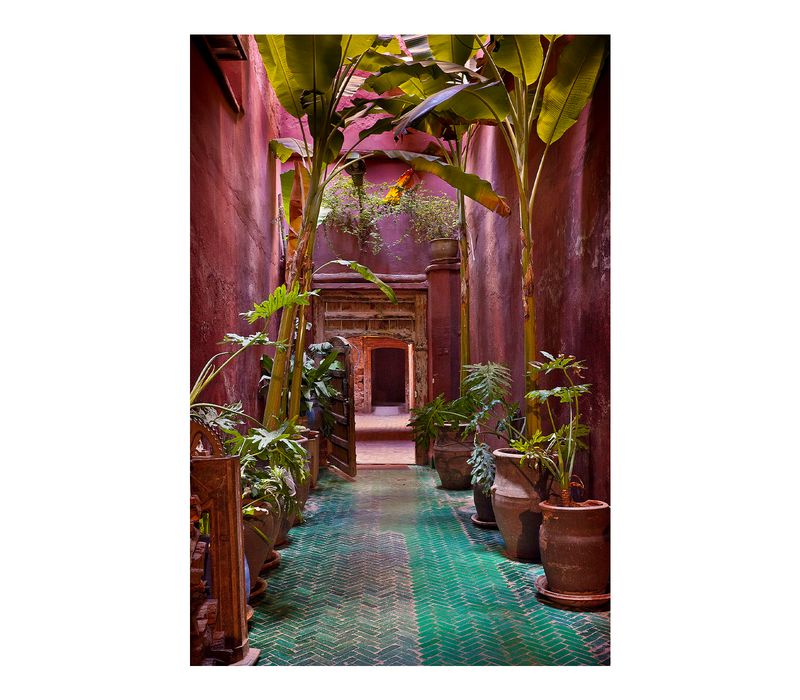

Riad Madani. Photograph by Mr Alessio Mei

Close encounters

Years ago, a very well-connected man in Marrakech gave Anna-Marie and I a private tour of a famous house. He was incredibly attentive, but only to me – Anna-Marie’s charms seemed invisible to him. Later, he sent me an elegantly worded and moving message, describing a profound connection he’d felt in our two-hour encounter, and inviting me to join him that weekend on the night train to Tangier. Flattered, I politely declined. But we had to admire his bold, unapologetic pursuit of romance. Morocco can do that to you: it’s a country charged with possibility and infinite promise; built on ancient traditions, it also thrives on in-the-moment spontaneity – a heady combination I never tire of. (PS: I have subsequently taken the night train to Tangier and my admirer was right – it is an unforgettable experience.)

Life lessons

I was sitting in a market one afternoon, drinking mint tea at a café. As the post-lunch bustle began to die down, I watched an old man in a thick, hooded Berber djellaba slowly wheel a giant wooden cart upstream through the dispersing crowd. It was slow going, his cart weighed down with a mountain of prickly pears. It was like he’d appeared out of another century, a glitch in time dropping him into this modern scene of sportswear and plastic toy vendors.

He manoeuvred his cart into a quiet corner – and waited. Nobody paid him any attention. I felt sorry for him: how he’d have to return home with nothing but rotting produce… Still he waited. It must have been 4.00pm when a swarm of people suddenly gathered around the old man’s cart in a frenzy of buying. I felt stupid: of course, he knew exactly what he was doing. This was his daily plot and these were his regulars. The thing is: from the outside, Moroccan life can often appear unstructured and chaotic, but, in its own way, it functions perfectly. Everybody is a working part of this weird but brilliantly calibrated system. There’s an important lesson in there somewhere.

For more travel recommendations, go to MR PORTER’s Style Council