THE JOURNAL

Businessmen in Oxford, 1994. Photograph by Mr Stuart Franklin/Magnum Photos

In the summer of 2006, the future British prime minister Mr David Cameron, then leader of the opposition, stood in front of an audience at a social justice conference to deliver what would become known as his “hug a hoodie” speech. The address followed the previous year’s controversy: the Bluewater shopping centre in Kent, England had banned shoppers from wearing hoodies in an effort to deter crime. The ban sparked a debate in England and Cameron urged his supporters to show more compassion towards alienated youths, not focus on how they’re dressed. At the same time, he also did little to curb people’s prejudices.

“We – the people in suits – often see hoodies as aggressive, the uniform of a rebel army of young gangsters,” Cameron said. “So, when you see a child walking down the road, hoodie up, head down, moody, swaggering, dominating the pavement – think what has brought that child to that moment.” Cameron didn’t think banning hoodies was the right solution. But he didn’t necessarily think it was wrong, either.

Sixteen years on, the high-end fashion world has had its own “hug a hoodie” moment, as designer labels have embraced streetwear and incorporated this fuzzy fleece garment into their lines. Hoodies can be found everywhere from Brunello Cucinelli to Balenciaga, and fashion writers are stumbling over themselves to describe new office dress codes that don’t involve suits.

Yet, the underlying issue that drove the 2006 controversy persists: we still debate what respectability means in what we wear. Fashion is not purely a creative art; our dress choices are not entirely a private matter. Our outfits are a visual language: just as a black leather jacket can make you look like a rebel rocker, a waxed cotton jacket paired with tailored moleskin trousers suggests a privileged upbringing. In countless op-eds published today, writers urge readers to pull themselves together and dress more “respectably”.

The idea that our clothing choices carry certain connotations is not novel. But respectability in dress is a particularly sensitive issue because it touches on people’s virtues, morality, and character, often carrying the weight of who is “deserving” in society. Respectability relates to who gets jobs and housing, their treatment by the police, and which public spaces a person is allowed to occupy.

This issue has become more fraught as people from different backgrounds are increasingly rubbing shoulders with one another. As Mr Stuart Hall, a Jamaican-born British cultural theorist, once wrote: “It should not be necessary to look, walk, feel, think, speak exactly like a paid-up member of the buttoned-up, stiff-upper-lipped, fully corseted and free-born Englishman, culturally to be accorded either the informal courtesy and respect of civil social intercourse or the rights of entitlement and citizenship.”

“Dressing ‘professionally’ nowadays requires you to know your audience. The best advice anyone can give is to make an effort”

Still, our judgments are not neutral or objective. We don’t only judge people based on their clothes; we also judge clothes based on the bodies underneath them. How we feel about specific fashions – what constitutes good or bad taste, reputable or disreputable – is often closely tied to how we feel about the people wearing the clothes in the first place.

Today, the archetype of respectability might well be a dark worsted suit. But at the turn of the 20th century, the suit was the baggy cargo shorts and dirty T-shirt of its day. Men in high positions such as finance, law and government wore the more formal frock coat; working-class clerks, administrators and shop workers wore the fustian lounge suit (what would be considered the business suit today). It took a great transformation in Western society for the monochromaticity of this broker’s uniform to become the emergent capitalist aesthetic, turning what was once considered sloppy attire into the sharp pressed image of propriety.

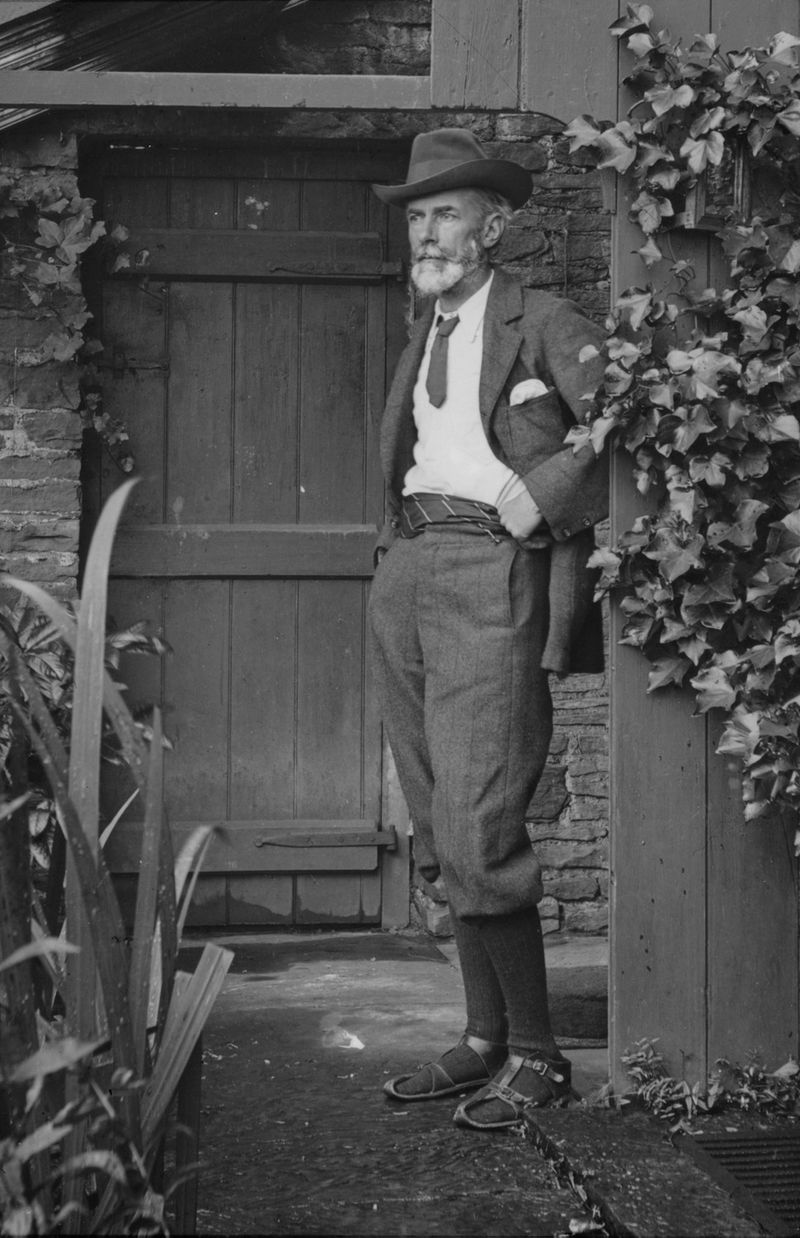

Mr Edward Carpenter, a late-19th century English activist and writer, was keenly aware of the tenuous connection between a person’s clothing and character. He was an early advocate of many progressive causes: women’s rights, gay rights, environmentalism, vegetarianism and a living wage. Carpenter loathed the hypocrisy of Victorian elites, who he felt weren’t preaching propriety with their clothes, but rather signalling their social class.

In May 1889, Carpenter wrote a letter to The Sheffield Independent about how 100,000 of the city’s residents struggled to find sunlight and air and endured miserable lives. While the Melton-clad plutocrats above wagged their fingers about dress codes, they concealed their cruelty under a veneer of refined manners. Carpenter rejected their buckram-reinforced clothing and opted instead for the working man’s suit, which he paired with open-toed, leather-strapped sandals that he fashioned himself.

Still, appearances undeniably matter. During his Masterclass, RuPaul gave this simple fashion advice: wear a suit. “You like money? Wear a suit. Put yourself together. People respond to it. It has nothing to do with you. It has to do with the narrative that’s already implanted in people’s consciousness. You don’t want to swim upstream. You want to work with what people already know.”

Clothes can help disadvantaged people become more upwardly mobile. Mr Mark Zuckerberg can countersignal all he wants in sneakers and jeans, as recognition is obvious, if not a mere Google search away. But, as author Mr Tyler Cowen wrote in his book The Complacent Class, the average 24-year-old striving to get ahead doesn’t have the same luxury and may need other ways to show their “seriousness” on the job.

Mr Edward Carpenter, Peak District, 1905. Photograph by Mr Alfred Mattison/National Portrait Gallery, London

Every culture has notions about decorum. There are times when we should dress in ways to show our respect for the occasion and people around us – weddings, funerals, religious events, etc. In a modern summary of Jewish law, Rabbi Eliezer Melamed once wrote: “One who is spending Shabbat alone should still dress up, because the clothes are not meant to honour the people who see them, but to honour Shabbat.”

After years of intermittent lockdowns, I try to dress up when sitting down with friends and family for dinner at a restaurant to honour the time between us, making it feel more special, rather than just an extension of life at home. When going out for dinner, I enjoy wearing single-breasted suits in lustrous cloths that perform well under artificial lighting, such as mohair-wool blends, or seasonal fabrics such as tonal navy seersucker to keep things cheerful.

If suits are too formal for the evening’s environment, I reach for sports coats made from seasonal fabrics such as wool-silk linen for summer and tweed for winter. And if tailored clothing is altogether too formal, I try to at least wear something nicer than I would have at home. A textured sweater paired with five-pocket cords looks sharper than T-shirts and jeans, but feels natural in any dressed-down environment.

Dressing “appropriately” for work has become a much more complicated matter, especially over the past few years, as workers slowly return to offices and navigate new and emerging expectations. Yet, it’s not true that workers can wear whatever they want. When the top brass at Goldman Sachs sent out an email in 2019 announcing they would allow their 36,000 employees to shed their coats and ties, they noted it wasn’t a free-for-all. Yet, they also didn’t give much dress direction. “We trust you will consistently exercise good judgment in this regard,” they wrote ominously. “All of us know what is and is not appropriate for the workplace.” Clearly, expectations still matter.

Ultimately, professional dress depends on your environment. In Silicon Valley, the suit is often looked at with suspicion, so workers earn the trust of their colleagues by wearing business casual. At the same time, when tech titans such as Zuckerberg and Google’s Mr Tim Cook appeared before the US House Judiciary Committee in 2020, they still wore what The New York Times fashion writer Ms Vanessa Friedman described as “trust-me suits”.

“That they wore such suits at all was a nod to the mores of Washington, because in their natural environment, denizens of the digital world often see the garments as sartorial shackles that reflect old ways of thinking,” Friedman wrote. “But these witnesses’ outfits, in their straightforward styling, both separated the chief executives from their traditional camouflage, thus making them seem less subversively Other, and conveyed respect for the office before which the men were appearing.”

Dressing “professionally” nowadays requires you to know your audience. The best advice anyone can give is to make an effort. When necessary, dress in ways that accord with people’s expectations of what it means to look trustworthy and respectable.

“Suits today are often sold on the promise that they’ll fashion you into a gentleman. But virtue is not an aesthetic and it cannot be inferred from the clothing on people’s backs”

At the same time, it’s important not to condemn people for their clothing, or read too much into their choices. We should not put the onus on young Black men to wear the correct sweater so they don’t get shot, for instance, or on women to wear the right leg covering so they don’t get assaulted. Clothing will not solve the deeper issues related to racism and sexism.

We also never know a person’s backstory. A job applicant may be wearing semi-casual clothes because they can’t afford a suit. Some people also don’t know how to dress and need a little guidance. Others may have difficulty finding clothes that fit. If you see a harried guest at a wedding, that person may have arrived after working three jobs to support their family – a more meaningful commitment to the institution of marriage than simply arriving in a two-piece suit for a wedding.

Suits today are often sold on the promise that they’ll fashion you into a gentleman; the timelessness of the suit itself is connected to the perceived stability of upper-class Britain. This is the world of horse riding, hunting, a love for country homes, business meetings in London, and preposterously expensive schooling. But virtue is not an aesthetic and it cannot be inferred from the clothing on people’s backs.

While notions of virtuousness are sometimes culturally dependent, certain themes emerge across time and space. To be virtuous is to treat those who are less fortunate with compassion, have a sense of justice, and be sincere.

Perhaps the best summation of what it means to be a gentleman can be found in Cardinal John Henry Newman’s short essay, “The Definition Of A Gentleman”, in which he notes, “He has his eyes on all his company; he is tender towards the bashful, gentle towards the distant, and merciful towards the absurd; he can recollect to whom he is speaking; he guards against unseasonable allusions, or topics which may irritate; he is seldom prominent in conversation, and never wearisome. [...] He is never mean or little in his disputes, never takes unfair advantage, never mistakes personalities or sharp saying for arguments, or insinuates evil which he dare not say out.”

It makes absolutely no mention of clothing at all.