THE JOURNAL

Mr Frank Stella at Gemini G.E.L. studio, LA, 1970 © Malcolm Lubliner

Minimalism matters: step into the white cube as MR PORTER pays homage to five pioneers of the understated aesthetic.

“Less is more”. Throughout his career the architect Mr Ludwig Mies van der Rohe repeated this phrase – which was actually first adopted by his mentor Mr Peter Behrens in the early 20th century. It’s the pithiest and punchiest of bumper sticker slogans for what we’ve come to think of as “minimalism” – an approach to creative endeavour that has its roots in 20th-century architecture and art but has exerted a lasting influence on almost all artistic disciplines, from music to product, design to fashion. Ironically, though all things we tend to think of as minimalist are easily identifiable by their blissful simplicity and clarity of purpose, the movement itself somewhat defies categorisation. Minimalist architecture – all straight lines, open-plan spaces and concrete and glass surfaces – is derived from (and often interchangeable with) the international style of modernism. Minimalist music, as pioneered by the likes of Messrs Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Philip Glass, seems upon first listen, oddly, to have an awful lot of notes flying about. In fashion, the word “minimalist” could be applied as easily to Maison Martin Margiela’s quasi-invisible branding and predilection for white-on-white as to the timeless restraint of Margaret Howell, two thoroughly different designers.

In addition, when “less is more” becomes “how much is enough?”, the minimalist approach has provoked animated, even aggressive, responses. When composer Mr John Cage premiered his most famous composition, 4’33” (consisting of four minutes, 33 seconds of silence) in 1952, people simply walked out. (“They didn’t laugh, they were just irritated… and they’re still angry,” he reflected in a 1982 interview.) When the Tate Gallery exhibited Mr Carl Andre’s artwork “Equivalent VIII” (a rectangular pile of bricks) in 1976, it was vandalised with blue vegetable dye. The rigidity of minimalism’s reductionism has been parodied in mass entertainment, from Absolutely Fabulous (which taught us that if you make your home a white cube, there’s nowhere to stash the booze) to The Simpsons – think of the early 1990s episode in which a Yoko Ono-esque character sits at Moe’s bar and orders “A single plum, floating in perfume, served in a man’s hat”.

“They didn’t laugh, they were just irritated… and they’re still angry” – Mr John Cage

However, while all this can’t be ignored, it’s also true that minimalism is now somewhat orthodoxy in both highbrow and popular culture. Once puzzling, the totemic sculptural stacks of the late artist Mr Donald Judd have become sacred, his spread of studios and spaces in Marfa, Texas a new art Mecca and a much-loved movie location – There Will be Blood and No Country for Old Men were partly shot there. The repeating loops and pulses pioneered by composers such as Messrs Cage and Reich have found their way into everything from the ambient electronica of The Orb to the super-complex folk of Mr Sufjan Stevens. In-demand architects such as Sir David Chipperfield (the man behind Valentino’s temple-like store in New York) and the Japanese duo behind SANAA have been described as neo-minimalists, while Sir Jonathan Ive, Apple’s design chief, is clearly a minimalist of sorts; the company’s most popular invention, the iPhone, is a shining example of the less-is-more approach.

Indeed, the term minimal is now thrown around so carelessly that you have to remind yourself that it has meant something quite specific in different media and at different times. And tracing minimalism’s history and development is not easy because so many of those who have been declared minimalists were far from comfortable with the tag. Having said that, there are a number of exceptional personalities that will always be associated with minimalism, thanks to their work’s exceptional economy of gesture and purpose. If you’re thinking about streamlining things this year, there are few better people you could look to for inspiration than the following five bare-bones visionaries.

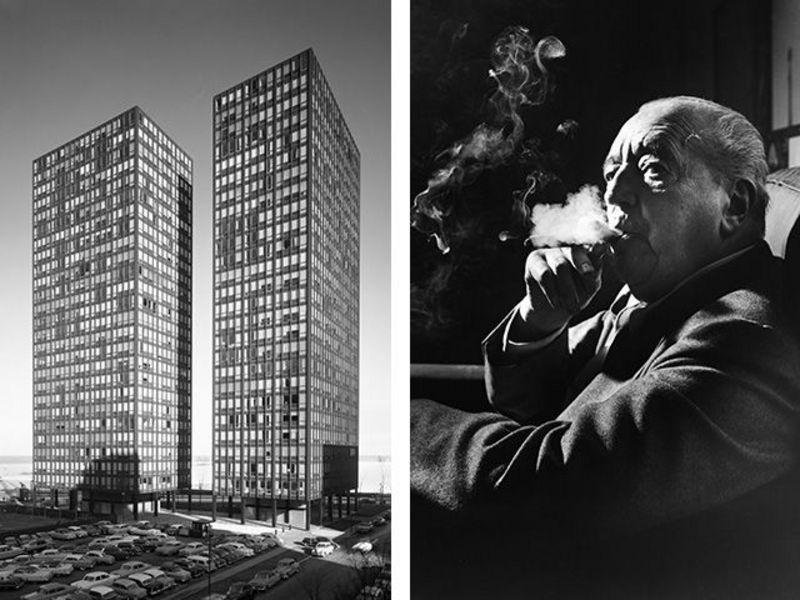

MR LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE

Left: North Lake Shore apartment buildings, Chicago, circa 1950 Hedrich-Blessing Photographers/ Chicago Historical Society/ UIG via Getty Images © DACS 2014 Right: Mr Mies van der Rohe, circa 1971 Hedrich-Blessing Photographers/ Chicago Historical Society/ UIG via Getty Images

Mr Mies van der Rohe is the towering figure of 20th-century architecture. He was born in Germany in 1886 and went on to apprentice with German painter and architect Mr Peter Behrens, working alongside Le Corbusier and Mr Walter Gropius before establishing his own practice. He was head of the Bauhaus school between 1930 and 1933 before leaving Germany for Chicago.

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas by Mr Mies van der Rohe, 1958 Hedrich-Blessing Photographers/ Chicago Historical Society/ UIG via Getty Images © DACS 2014

Pulling together elements of Russian constructivism (particularly the emphasis on industrial materials and design efficiency), the clean lines and stark colours of the Dutch De Stijl group and the free-flowing spaces of Mr Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie style, he developed an architecture that was for functional honesty and against superfluous decoration, about light and lightness, openness and transparency, glass and steel. He designed a series of what are now iconic buildings, refining and defining modernism as he went along: the Barcelona Pavilion of 1929, a revolutionary single-storey structure built in fine materials such as marble and onyx, which blurred the ideas of interior and exterior space; the Farnsworth House, the definitive modernist glass box; the Lake Shore Drive apartment blocks in Chicago, the model for all glass and steel skyscrapers to come, completed in 1951; and the Seagram Building in New York in 1958, the masterpiece of muscular corporate modernism.

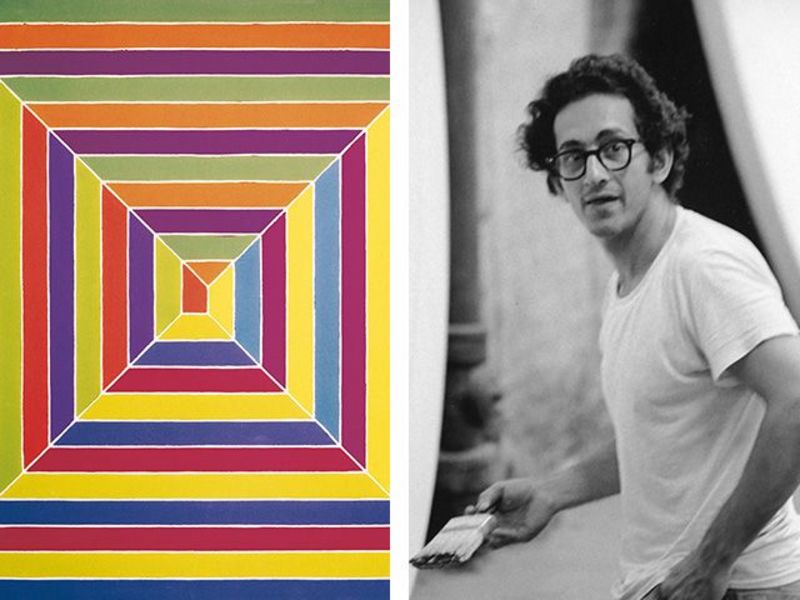

MR FRANK STELLA

Left: “The Gallant Indies (Les Indes galantes)”, 1966, private collection Bridgeman Art Library © Frank Stella. ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015 Right: Mr Stella in his studio, New York, 1968 © Malcolm Lubliner

In art, the term minimalist is usually applied to a particular set of artists, mostly working in New York, who arrived after the mighty abstract expressionists – Messrs Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko and the rest – had seemingly condemned figurative art to the dustbin of history.

For the abstract expressionists, art was still a matter of splashing something of the soul on the canvas, or a gargantuan struggle to render the sublime. It was heroic and it was personal. Minimalism, on the other hand, harked back to Malevich, Mondrian, Bauhaus and De Stijl, and was more about form, geometry and material – optics rather than emotion, metaphor or symbol.

Installation photograph of a Frank Stella exhibition at the Dominique Lévy Gallery, New York, 2012 Courtesy of Dominique Lévy Gallery. Photo Tom Powel Imaging, Inc. © Frank Stella. ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015

Mr Stella graduated from Princeton in 1958 and immediately moved to New York. Fiercely intelligent and already immersed in the city’s art scene, he had his big idea early. He would produce paintings that were about nothing but the paint. His stark black stripes of the late 1950s are seen as minimalism’s starting line. “Art excludes the unnecessary. Frank Stella has found it necessary to paint stripes. There is nothing else in his painting,” commented Mr Andre. Mr Stella said simply: “What you see is what you see.”

MR DONALD JUDD

Left: "Untitled - 77–41 Bernstein", 1977, private collection Christie's Images/ Bridgeman Art Library. © Judd Foundation/ VAGA, New York/ DACS, London 2015 Right: Mr Judd assembling his work for an exhibition at the Castelli Gallery, New York, circa 1966 Bob Adelman/ Corbis © Judd Foundation/ VAGA, New York/ DACS, London 2015

Though the painter Mr Stella spearheaded it, artistic minimalism expressed itself most powerfully in three dimensions. There were Mr Dan Flavin’s carefully controlled compositions of coloured fluorescent lights. There were Mr Larry Bell’s mesmerising glass cubes. There was Mr Sol LeWitt’s conceptual geometry. But most strikingly simple of all were Mr Judd’s “specific objects”, particularly his vertically aligned, precisely engineered boxes of stainless steel, anodised aluminium or Plexiglas.

Mr Judd, almost a decade older than Mr Stella, had studied philosophy and art history. During the early 1960s he worked as an art critic and theorist and his writings would become hugely influential, while as an artist his work progressed through painting and woodcuts to his pristine stacks.

Inside one of the 15 outdoor concrete works by Mr Judd at the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas, 2006 Jill Johnson/ Fort Worth Star-Telegram/ MCT via Getty Images © Judd Foundation/ VAGA, New York/ DACS, London 2015

Mr Judd was intent on severing links with the grand European tradition. His “specific objects” were not sculptures in the traditional sense. His works weren’t representations of anything. They were simply objects in space. And the space they created – the negative space – was as much part of the piece as the object itself. “Actual space is intrinsically more powerful and specific than paint on a flat surface,” he said.

Mr Judd also insisted that his art could be produced by skilled manufacturers, who could make a better fist of it than he could. The intent was the thing – though they were very definitely art. He would later design furniture – and his influence on contemporary design has been profound – but was always careful to insist that his desk was a desk and not a “specific object”.

MR JOHN PAWSON

Left: Moritzkirche, Augsburg, Germany, 2013 View Pictures/ Rex Features Right: Portrait of Mr Pawson in his London home Orla Connolly

Though the term has been applied to the Mexican architect Mr Luis Barragán and Japan’s Mr Tadao Ando, what most people now think of as minimalist architecture is exemplified by the work of Mr Pawson, whose reputation and influence far outweighs his actual output.

When he emerged on the architectural scene in the early 1980s, Mr Pawson seemed heaven-sent, promoting calm and order after the clutter and discordancy of post-modernism (an architectural movement that made some sense on paper, but not so much in bricks and mortar). His minimalism was all about architecture rediscovering its soul and sense of the sublime – an idea that was, oddly, in exact opposition to the mission of minimalism in art.

Montauk House, Long Island, US Gilbert McCarragher www.gilbertmccarragher.com

Mr Pawson didn’t start formal architecture training until he was 30 and never completed it (a cause of residual sniffiness among some of his fully qualified peers). But by the time he started, he already had a clear idea of what he wanted to do. As it had been for Mr Lloyd Wright way back in the 1920s, Japanese architecture was a key influence on Mr Pawson. He had been travelling and teaching in Japan, intent on becoming a Buddhist monk but instead drifting into the circle of the designer and architect Mr Shiro Kuramata. And when he finally came to create spaces, whether a monastery in Bohemia, a Calvin Klein store on Madison Avenue or a house in Tokyo, they were temples to perfectly executed emptiness: elegant balance, the best materials, perfect proportion, pure white or grey planes, and the slow movement of light and shadow. This was material meditation but, and in a clear link to the work of Mr Judd and his expertly tooled stacks, they required the sharpest angles, the strictest of tolerances. Mr Mies van der Rohe had an aphorism for this too: “God is in the details”.

Mr Naoto Fukasawa

Left: MUJI wall-mounted CD player by Mr Fukasawa, 2000 Courtesy MUJI Right: Studio portrait of Mr Fukasawa Courtesy Vitra

Japan has had a major influence on minimalist design. It is the Japanese designer Mr Fukasawa, alongside his friend and Brit, Mr Jasper Morrison, who has come to define minimalist design. Mr Fukasawa has designed furniture and electronics, taking Mr Dieter Rams’ muscular functionalism and bringing to it a perhaps more organic sense of pure form. He has also been a long-serving advisor and designer for MUJI (he designed the famous wall-mounted CD player) and you can see the Japanese socks-to-stationery chain as the champion of an everyday, accessible minimalism. His rice cooker for MUJI and the humifidier for his own ±0 (plus minus zero) brand – elegant curves and barely-there buttons and displays – exemplify what Mr Fukasawa has called “super normal” design – objects that turn visual and functional economy into a kind of art.

Chair by Mr Fukasawa, 2007 Courtesy Vitra