THE JOURNAL

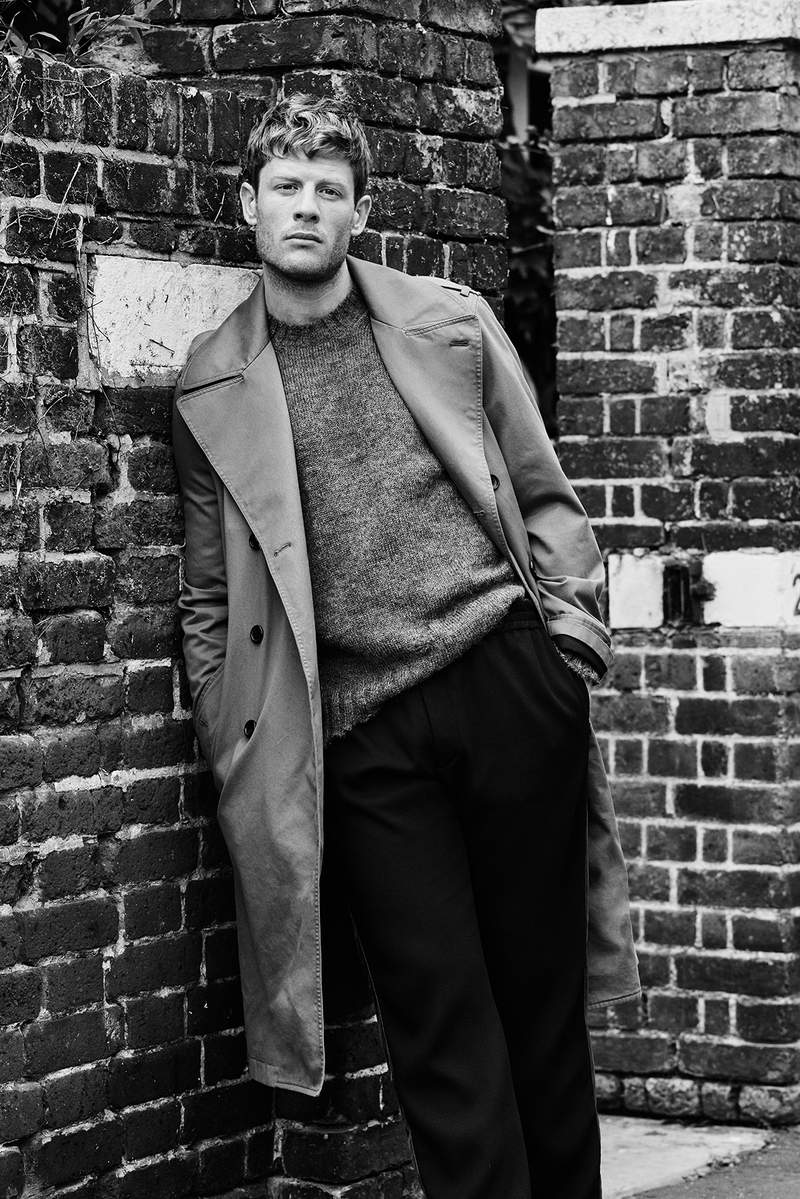

Mr James Norton is not a man to be underestimated. The first time I noticed the London-born, Yorkshire-raised actor, he was playing an earnest young lover in Death Comes To Pemberley, a cosy whodunnit set in the world of Ms Jane Austen’s Pride And Prejudice. I had him down as a production-line fop, the kind that elite English schools crank out as reliably as the Disney Club cranks out Mouseketeers. He seemed… nice. Agreeable. The sort of teacake your granny would like.

I certainly couldn’t see him pulling off someone such as Tommy Lee Royce in Happy Valley, the most haunting TV psychopath of recent years. Or earning admiring reviews from the Russians for playing their national literary hero, Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, in the all-star BBC adaptation of War & Peace. But in projects as varied as the clerical mystery Grantchester and dystopian drama Black Mirror, Mr Norton has demonstrated that enviable quality – range – and has configured his career to use it to the fullest.

“That’s the joy,” he says. “Most actors would agree that the reason why you go into the job is that there’s a hunger for experience, a general inquisitiveness. When you have a group of actors at a restaurant, everyone will try everything. It’s not just a sensory thing. It’s about wanting to suck up everything that life can offer.”

Life is offering Mr Norton, 32, a lot right now, and it couldn’t happen to a more grateful individual. His conversation is peppered with “I’m so lucky”, “It’s a privilege”, “One of the joys”, etc. His first Hollywood studio production, Flatliners, is about to hit cinemas. It’s a remake of Mr Joel Schumacher’s cult 1990 psycho horror, which starred Mr Keifer Sutherland and Ms Julia Roberts, about a group of medical students experimenting with near-death experiences. In the remake, Mr Norton stars opposite Ms Ellen Page and Mr Diego Luna. And he’s taking the lead as the son of a Russian mobster in McMafia, a BBC/AMC international co-production that stands out in the autumn TV schedules. “One of those situations where everything is in place, and all you need to do as an actor is not fuck it up,” he says.

One of the co-writers is Mr David Farr, who adapted Mr John Le Carré’s The Night Manager for BBC, which was widely seen as Mr Tom Hiddleston’s audition for the role of James Bond. So it will do Mr Norton’s chances of leapfrogging his fellow Cambridge graduate on the shortlist no harm at all. They’re both 8/1 with William Hill. “It’s nice to be in that conversation,” he says. “But I’m certainly not saying no to stuff because I’m holding out for that.”

For now, Mr Norton has asked me to meet him at the National Theatre in London. I assume he’s in rehearsals for some top-secret project (though he does confess an ambition to play Hamlet here one day), but no, he just wants to spare me an off-Tube trip to Peckham in south London, where he lives. He turns up in “vegan trainers”, made by Veja, black Levi’s and an old grey cashmere jumper, with what looks like a duelling wound on his neck but turns out to be a scar from an operation on an old rugby injury. He is profusely apologetic for being approximately five minutes late. And prays leave for another 60 seconds of my patience so he can purchase a croissant.

He’s a Type 1 diabetic and a “little munch” will ensure he doesn’t die during the course of our interview. Mr James Geoffrey Ian Norton grew up in a timeless bit of North Yorkshire and remains a country boy at heart. It is rare that he passes a body of water in which he doesn’t want to take a dip. “I love being outside, swimming in the lido or Shadwell Basin,” he says. “There’s a bridge near where my parents live where you can jump in. It’s so wholesome and English.” His dream is to have a river in his garden, so he can frolic among the trout and herons each morning. His childhood was idyllic but also instructive. Both his parents are academics, both took an equal role in domestic duties and both encouraged reasoned debates around the kitchen table. Young Mr Norton was sent to Ampleforth boarding school (posh, monastic, Catholic) and went on to study theology and philosophy at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, before a spell at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. People often assume he’s religious – the dog collar he wears for the 1950s period piece Grantchester doesn’t help – but he says his youthful interest in Christ was more one of “moral intrigue and the love of storytelling. I loved the gospel reading at mass every Sunday. But it became a relationship of intrigue rather than belief. And most of my degree was about Hinduism and Buddhism in any case.”

Still, you can see why he makes such a convincing vicar in Grantchester and why he’d want to break away from that mode. “I remember early on in my career people would say to me things like, ‘You have a very period face.’ I was like, what does that mean? They’d seen me in a couple of period dramas and imagined that would be my career.”

So he was elated when the supremely depressing Happy Valley came along. Ms Sally Wainwright’s critically lauded BBC series (now streaming on Netflix) gave him the chance to play a working-class ex-convict whose soul descends to the very depths of hell. “I will be forever grateful for that role,” he says. “To be given the opportunity to prove myself like that was just great.” He sees each role as a licence to go out and learn. “Not just from an academic point of view, but in an emotional, embodied way. The word we always use is empathy. There’s nothing more powerful than that. I’d never managed to empathise with a serial killer from any article about them, but when you’re actually inhabiting them, you have to learn to love them, however abhorrent they are.”

I guess it’s about getting to know the part of yourself that could kidnap and torture, were circumstances different. “It’s like undergoing a crude form of psychoanalysis on your own,” says Mr Norton, but confesses that it’s also kind of fun. “I’ve been wary talking about this because it could be misconstrued,” he says slowly. “But it was incredibly empowering not to care at all what people think, to go the other way and want people to be afraid of me. For someone like me, who goes around the whole time being very polite, to be allowed to spend some time not giving a fuck what people think was fucking cool.” He smiles bashfully. “I remember walking on set and seeing people’s reactions to me with a skinhead and tattoos. People started to treat me completely differently.”

He’s no method actor. He and his co-star, Ms Sarah Lancashire, tried to keep the mood light between scenes. But still, he found Tommy hard to shake off. “He’s so mistrusting of the world,” he says. “The sadness in that character was that he thought the world was so inherently hostile that the kindest thing he could do for his son was to take him away from this suffering. That’s dark.” He was haunted by “weird, dark dreams, me being horribly abusive”.

McMafia ought to draw on similarly dark currents, albeit in more glamorous circumstances. Mr Norton plays Alex, a “Michael Corleone-type Russian guy”, who ends up being pulled back into the family business (crime, extortion, money laundering) despite his efforts to escape. “His dad was a Mafia boss who was exiled by Putin, but Alex has tried to turn his back on that and set up his life properly, with a fiancée and a good job.” Mr Norton is particularly excited about this one. Mr Farr’s co-writer is Mr Hossein Amini, who created Mr Ryan Gosling’s tour de force Drive, and it’s inspired by investigative journalist Mr Misha Glenny’s book. The cast includes highly respected Russian actor Mr Aleksey Serebryakov (from Leviathan) plus a host of stars from Israel, Mexico, Brazil and Turkey. “It was such an interesting set,” says Mr Norton. “I don’t think there can have been many casts like it. And with what’s going on with Trump, Russia, the Panama Papers, all that, basically our show lifts up the curtain and shows what state-level corruption looks like. The Mafia isn’t a family with a protection racket in a city. It’s a multi-national globalised corporation where all the parts are linked. You always want to be chasing the zeitgeist. With this, for the first time in my life, I felt the zeitgeist was chasing us.”

On Flatliners, he seems a little more tentative, perhaps wary of incurring the wrath of fans of the original movie. “Everyone remembers it very fondly,” he says. But it was the first time he’d been let loose in a big studio. “The money, the toys, the stunts – Ellen and Diego had done all that before, but I was like this token Brit, running around having lots of fun.”

As for the other sides of success, he’s readjusting. Last we heard, Mr Norton was in a relationship with Ms Jessie Buckley, the English actress who played his sister in War & Peace, but when I ask about his love life he makes a complicated face and asks if we can avoid this particular subject. “Having this dream job, it compromises family, friends, relationship, because you’re always away,” he says. “I have 12 cousins and we’re all very close, but there have been a few family occasions where I’m the only one who isn’t there. And your relationships do take hits.”

He’s politically engaged, too – “As I think we all are right now” – but isn’t sure if and when to use his celebrity to promote his causes. “I must be the most boring person to follow on Twitter,” he says. He essayed a few politically themed tweets recently, but found the response a bit dismaying. “I tweeted a photo from an anti-Brexit march a few months ago, and said, ‘Let’s get behind a second referendum, there is hope!’ and I’ve never received so much hate and vitriol. And I thought, what’s the point? Well, there is a point, but maybe that’s not the right way to make it. Maybe it’s better to start a conversation, to listen rather than to shout.”

That doesn’t seem a bad idea. He’s itching to get behind the camera, he says. He has stories he’d like to tell. “I don’t want to be sanctimonious, but I’m interested in using my voice as an artist to…” He trails off – that English habit of not quite finishing his sentences – before remarking how much he admired Mr Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake, a devastating indictment of the British welfare system. But it seems his own thoughts are more to do with young men and their place in the world. He’s been reading Narcissus And Goldmund by Mr Hermann Hesse, which is about two monks taking divergent paths through the world – one as an artist, one as a thinker – at the time of the Black Death. It seems to have struck a chord.

“There’s a lot of confusion now about men’s place in the world,” says Mr Norton. “There needs to be a conversation. I’m putting together a script about how a young man deals with that confusion. We’re being pulled in different directions. I think for women, the feminist movement is a lot clearer. And we do need to redress pay inequality and, of course, men are implicated in that. But we also need to recalibrate our own position. Men whose identity is to do with being a protector and provider and full of testosterone are finding it harder.”

When it comes to redressing the gender imbalance, however, he seems more than happy to take one for the team. He is a reliable source of “phwoar”-style headlines in newspapers. “Female actors have been putting up with this tenfold for ever,” he says. “So I don’t feel male actors have a particular right to cry out about this. I don’t feel objectified, put it that way.”

Flatliners is out on 29 September