THE JOURNAL

A rookie’s guide to two very different ball games that baffle sports nuts from either side of the Atlantic.

On the face of it, baseball and cricket are fairly similar sports. They both involve one team hitting a ball with a bat in an attempt to score runs while another team attempts to stop them by getting them “out”. They’re both deeply ingrained in the national psyches of their respective countries, too. Baseball is often referred to as “the US’s national pastime”, and it’s hard to imagine a more quintessentially English sport than cricket.

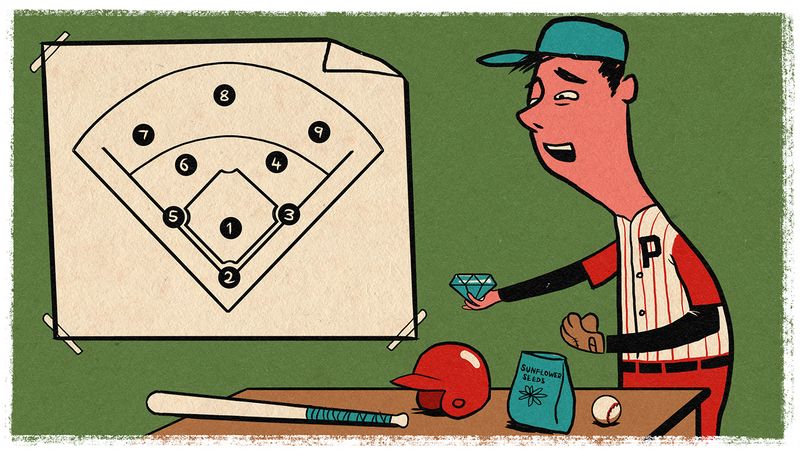

This is where the similarities mostly end, though. Where bowlers in cricket have leg breaks, googlies and off-cutters in their arsenal, pitchers in baseball rely on knuckleballs, sliders and splitters. The fielding positions in baseball are easy to remember: just three basemen, three fielders, a catcher, a pitcher and a shortstop. Wander on to a cricket field, though, and you might find yourself standing at third man, deep square leg, gully, backward point or silly mid-on.

Confused yet? Us too. It’s little wonder these two sports are so incomprehensible to the uninitiated. In an attempt to bring a little clarity to the matter, we invited two lifelong aficionados – one a baseball fan, the other an ex-cricketer – to talk bats, balls and the manifold idiosyncrasies of these two summer sports, and attempt to explain their respective appeal.

Baseball for beginners

The first time I saw my grandfather cry was at a baseball game. It was 25 September 1973 –“Willie Mays Night” at Shea Stadium in Queens, New York. Mr Willie Mays, known as The Say Hey Kid, was retiring as a New York Met after a career composed of jaw-dropping catches and explosive hits. Both my grandfather and Mr Mays had travelled far in their lives. My grandfather had grown up in a tenement on New York’s Lower East Side. While attending high school at night, one of his jobs was selling peanuts at the Polo Grounds, the stadium where Mr Mays had played in his prime as a member of the New York Giants. Mays had started his professional career in Alabama playing for the Birmingham Black Barons, among other teams in the Negro American League. He traded segregation for celebrity, while my grandfather traded poverty for prosperity.

Many of our nation’s teachable moments are contained within this game – civil rights, immigration, competition and the morality tale of performance-enhancing drugs. When bringing European friends to their first baseball game, I try to focus less on the rules and statistics and more on the atmospherics. Since baseball plays out over a season from roughly April to September, I explain how following a team brings me the same sense of relaxation as working through a sprawling historical epic (or binge-watching a long-running TV series). Characters come and go. Unlike literature, the saga of your hometown team cuts across the lines of race and class: your boss and your barber will both have an opinion about last night’s game. The pace, punctuated by the pitcher’s deliberations, allows for conversation, for drinking beer and eating hot dogs or regional delicacies like a Philly cheesesteak or a Baltimore crab cake.

“Following a team brings me the same sense of relaxation as binge-watching a TV series”

I recommend to my foreign friends that they read the local tabloid newspaper on game day because subtext in a player’s personal life makes for richer context when watching events unfold on the field. A few weeks ago, The New York Post ran a front-page story about how one of the Mets’ starting pitchers had sired two children with a woman other than his wife of 21 years. He happened to turn in his worst performance of the season on the day the story broke. I couldn’t help watching him struggle on the mound and thinking about what kind of phone calls he must have endured juggling wife and mistress.

Finally, I appeal to the inner Mr Alexis de Tocqueville and explain that baseball is a window into the American mindset. Of our three great American sports – baseball, football and basketball – baseball harkens back to our pastoral beginnings. Football is the game most closely tied with the industrial era. It is played on a field known as a gridiron, a large rectangle that echoes the layout of city blocks. Basketball, played indoors on a hardwood floor, is our post-industrial, inner-city pastime. The big grassy expanse of a baseball field, known as a “diamond” (from the shape that the four bases create), recalls our agrarian roots, and baseball’s gear has a decidedly anachronistic feel: bats are still made from ash and maple wood, the best gloves from leather, the ball is horse or cowhide wrapped around cork. When I bought my son Nicholas his first glove at age four, the smell of the glove oil and the process of bundling a ball inside the pocket, sticking it under his mattress and then having him sleep on it for a few weeks to break it in took me back.

Neither American football or basketball has infiltrated the fabric of American lives as much as baseball. One could hate sports, but still love baseball for the way the slang of the game has become such a rich part of the American language.

“Neither football or basketball has infiltrated the fabric of American lives as much as baseball”

Baseball-inspired colloquialisms appear at work (“that’s a homerun idea”) and in our sex lives (“She only let me get to third base”). When an assignment plays to someone’s strengths, it is said to be in his “wheelhouse” (the area of the strike zone where a batter can unleash the most power). “Chin music” is an American idiom for a warning, derived from the way a pitcher might throw close to a batter’s head to get him to stop crowding the plate.

Probably more than any other strain of American sports fan, baseball devotees can appreciate cricket the easiest. Central to both games is the drama of a bowler looking to defeat a batsman with a range of different deliveries. Baseball has the knuckleball and the curveball, cricket the googly and the leg cutter. Where we part company is the pace. When my 11-year-old son Nicholas visited London a few summers ago, he found himself sucked into watching cricket as a sort of substitute for baseball. I was getting dressed for dinner after a long day of sightseeing while he was camped out on the hotel room bed. Much was familiar and comforting on the TV screen – the green grass of the Marylebone Cricket Club; the crack of ball on bat; the soft patter of the announcers, but there was one element he could not abide. “Dad, this game is mental,” he yelled. “This guy has been batting for 45 minutes, and he shows no sign of stopping.” He then tossed off some typical American bravado. “I bet if we moved here, I could be good at this game.”

I thought of my grandfather working at the Polo Grounds, and made a mental note that our next trip, we Americans sprung from tenement stock would have to make a trip to the pavilion at Lord’s and see what all the fuss was about.

A crash course in cricket

Even Mr Don Bradman couldn’t do it. Explain cricket to the Americans, that is. In 1932, Mr Bradman, the world’s greatest cricketer, was invited to the private box of Mr Babe Ruth, the finest baseball player, in Yankee Stadium. As the two great men compared notes, Mr Bradman tried to explain that a batsman in cricket, having hit the ball, earned the right but not the obligation to run. Mr Ruth was nonplussed. “Just too easy!” he reflected. Mr Bradman’s reply is unrecorded. “Perhaps he was right,” Mr Bradman later wrote, “but I should have been delighted to see him try.”

Whereas Mr Ruth found the idea of playing cricket “too easy”, explaining cricket to Americans has typically proved too hard. Many Brits, even those possessed of fine explicatory powers, have flopped embarrassingly when confronted with the ultimate challenge: “Go on, explain this cricket business to us.” Indeed, many otherwise confident English conversationalists have disappeared into this lethal trap, like those early mountaineers who ended up frozen into the north face of the Eiger.

From hard-earned personal experience, keeping things short and pithy offers the best chance. “Cricket is baseball on valium” usually helps Americans to locate the general mood. The line is not mine, alas, but stolen from the late comedian Mr Robin Williams. Sketching the ambience is certainly easier than plunging hopefully into technical details – one man goes in to join his team-mate at the non-striker’s end after another one has got out. Even writing those words, I get flashbacks: blank American faces starring at me, totally lost.

“‘Cricket is baseball on valium’ usually helps Americans to locate the general mood”

The problem with cricket and baseball – in terms of explaining one to fans of the other – is that they are too similar to ignore the parallels, and yet strangely opposed in fundamentals. I learned this when I was writing my book Playing Hard Ball, comparing the two sports. At the time, I was a professional batsman in cricket. But I felt a far closer affinity, from a psychological perspective, to the baseball pitcher than to the batter. Why?

The answer lies in the vastly different size of the scoring unit. In cricket, runs are relatively cheap – on average, one team might get 350, the other 300. When translated into pressure, this means that the batsman is “expected” to win any single piece of a cricket match. Stop the action and ask, “Who ought to win the next moment?” and the answer is the batsman. That is a question of simple probability, because runs are much more common in cricket than wickets (“outs”).

The situation is reversed in baseball, where a typical score might be 4-2. Outs are more common than runs. It is the pitcher who “ought” to win the next moment of play. If this sounds like good news for the cricket batsman and the baseball pitcher, think again. With expectation comes pressure. When a batsman gets out in cricket, his day is over: he spends his professional life with a guillotine hanging over his neck. A baseball pitcher is only marginally better off: the manager’s slow walk out to the mound, and banishment from the game, might come at any moment. When I realised that my cousins were those haunted pitchers rather than those muscled sluggers, that was the moment when I settled into an enjoyably partisan experience of baseball.

“The style and language of cricket works against Americans taking it seriously”

Explaining cricket presents a final curveball. The style and language of cricket, which survives from the age of amateurism, works against Americans taking it seriously. Wearing whites? Stopping for tea? Inviting the opposition to bat first? Come on, you cannot be serious. Living in New York in my early twenties, if I was introduced to Americans as a “professional cricketer”, the commonest follow-up question was, “But you can’t make a living as a cricketeer, can you?” (“Cricketeer” as in musketeer.)

They have a point, given the enduring echoes of the village green, even within the professional game. When Mr Andrew Flintoff, the hard-hitting all-rounder, briefly took up professional boxing after his cricket career, his debut fight was against the American Mr Richard Dawson.

At the press conference, Mr Dawson explained his background: from the American South; been shot four times; ex-prisoner; now works as a debt collector.

“I used to play cricket,” Mr Flintoff replied. “If you’ve not seen it, Richard, we dress in white and stop for sandwiches every two hours.”

Mr Ed Smith is an author and broadcaster. He played cricket for England and captained Middlesex. He is now course director of a new MA in the History of Sport 1800-2000 at the University of Buckingham

Illustrations by Mr Adam Nickel