THE JOURNAL

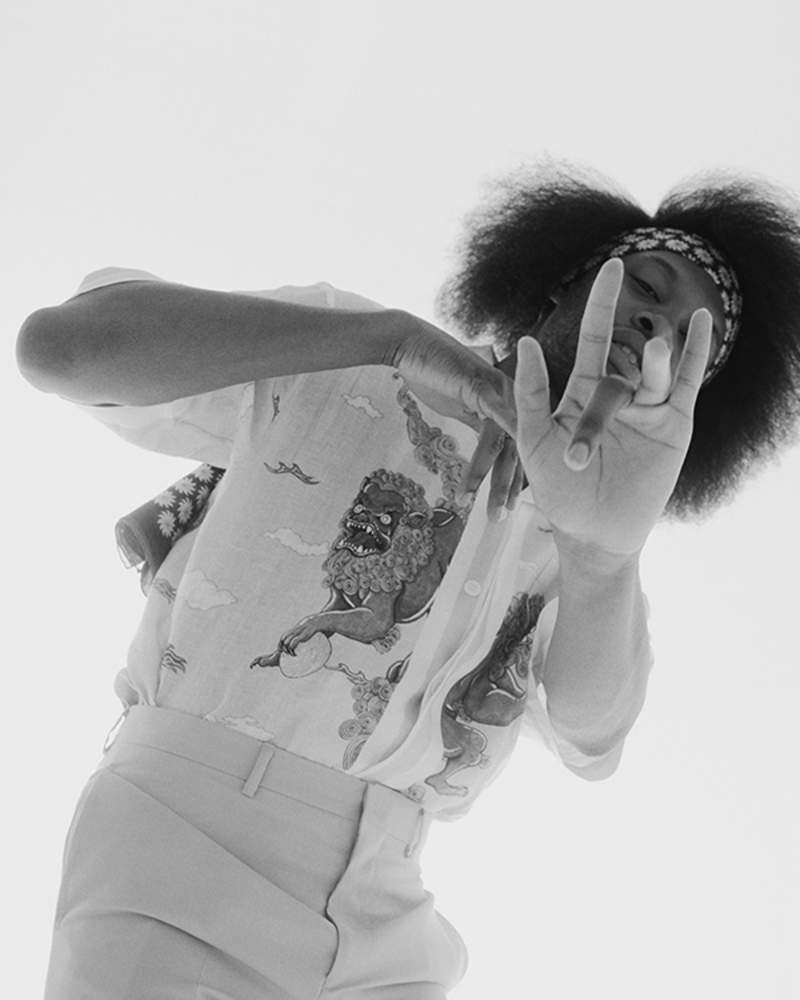

Isolating With Mr Jeremy O Harris, This Generation’s Most Provocative Playwright

Tucked into his temporary London bolthole, where he is taking shelter from the coronavirus crisis, Mr Jeremy O Harris finally has a second to reflect on his dizzy professional rise. Last year, after all, the 30-year-old American writer-actor created a stir by getting one of his plays on Broadway (and two plays staged off-Broadway), while simultaneously finishing a masters degree at Yale School of Drama. He had decided to become a writer just five years ago, and his first commission only dates back to three. He’s appeared on late shows, on the pages of Vogue and GQ and has signed a two-year development deal with HBO. One magazine has already called him “the queer black saviour the theatre world needs”. Although, on one hand, he is rightly proud of such recognition, on another he knows it’s quite mad.

“If anything, it’s like someone tapped a cheat code into a game for me and I’m on, like, level 45,” he says over the phone when we speak, bright, rigorous and relentless. Like his work, he is candid about his success: “Like, one minute I started the game, next I was here. And it’s really exhilarating and fun, but it’s also something where I keep reminding myself that it’s OK for me to fail. Because, I’m still, like, new at this, you know?”

Mr Harris came to London in March to oversee the UK premiere of his play, “Daddy”. Like his other hit, Slave Play, it is a funny, ambitious, unsettling piece, which tackles many issues of race and sex – and nails how the two are often uncomfortably linked – head-on. The Covid-19 pandemic has now postponed the Almeida Theatre staging until summer, at least, but to be frank, the delay won’t much dull his momentum. The Virginia native also recently provided the screenplay for the crime caper Zola, a Sundance Festival standout, and has many other things in the pipeline, too. He chose to not rush back to the US, where he splits his time between New York and LA, “because for me going to an airport and flying felt more anxiety-inducing”. So, speaking from his rented flat, where he goes out onto the terrace every day to do “my morning constitutional”, he explains that he’s treating quarantine as “my own little residency”, as he works on “a couple of screenplays, some TV stuff [he is co-producing season two of HBO’s much-loved Euphoria] and a play.” In short, the pandemic hasn’t stemmed his output. “I don’t see any disruption – I see it all as extra fertiliser for the soil.”

Since we are speaking on the phone, I can’t provide much extra detail on Mr Harris’s physique, which by all accounts is striking. An imposing 6ft 5in presence with a regularly rotating hairstyle (see his Instagram for more), he has also rapidly become a fashion darling, seen at Gucci shows and the like. “Daddy”, for instance, set in LA’s wealthy art world, glories in style references (“Alessandro [Michele] is bae”). This is entirely logical for Mr Harris, where the clothes and the music and the visuals are as important as the words; Rihanna’s “Work” book-ends Slave Play, while “Daddy” riffs on Mr George Michael’s “Father Figure”. When he picks up the phone, he has just had King Krule’s new album “on repeat”. As for fashion, he’s been having a hoot infiltrating its upper tiers.

“Being able to DM a question to Alessandro Michele or Nicolas Ghesquière to mine a bit of inspiration for the next piece I’m doing is so exhilarating! My plays are all collages of all my influences – and I think that fashion is a great example of a medium that has that as their practice all the time. No collection is ever based on one influence. I feel a lot of affinity for fashion designers, because I think our brains work in the same way.”

Mr Harris’s first play of sorts came about five years ago, when he was living in LA, a self-confessed “man about town”. He had come to the City of Angels after dropping out of drama school in Chicago and was mostly, in his dry telling, “hanging out, basically. I was out a lot. And I was very good at being at a party – like, too good!” A naughty laugh. However, whether he was working the door of a club or in an art gallery, he was meeting the right people, such as the musician Ms Isabella Summers of Florence + the Machine. Together they devised the play Xander Xyst, Dragon: 1, about two dates that go deliriously awry, staged at the ANT Fest in New York in 2017. “That was really, really, really special,” he says. “Something clicked.”

It set off a sequence of quick, connected events, which Mr Harris calls “domino pieces” – he first got a place at the prestigious MacDowell Colony, where artists are invited to come and create, and it was there that another playwright, Ms Amy Herzog, advised him to apply to Yale. And the pinnacle of all this, obviously, is the staging of Slave Play on Broadway, then “Daddy” off-Broadway. Both quickly became notorious for their wit, their provocation, their frank depictions of sex and, yes, their undeniable style. In “Daddy”, a young black artist enters into a morally murky relationship with a much older white art collector; in Slave Play, a trio of modern interracial couples try to address their sexual problems by reenacting slave-master scenarios in the antebellum US. They have raised eyebrows – one recent headline called Slave Play “the most controversial play on Broadway”. At a Q&A in New York last autumn, he was angrily heckled by a white woman calling it racist against white people. He responded eloquently and sharply, first in person and later on Twitter. If nothing else, it laid bare the ways in which Mr Harris’s writing goes to places a lot of plays would never dare – it’s something he embraces.

“I’m sort of an equal opportunity provoker,” he says today. “What I love more than anything is debate. I’ll debate the wokest person, or the least woke person, around the legitimacy of their thought processes. Which is exciting, you know? And I think that’s what makes good drama.”

Mr Jeremy O’Bryant Harris was brought up in Martinsville, Virginia, by a single mother who managed to put her precocious child through the local Carlisle private school. His father was not in the picture, a reality that hit home for him as he was writing “Daddy” – which he calls “sort of my own exorcism of my own daddy issues”. Just a few days before its New York premiere, a friend took him to lunch and said the piece still didn’t feel “honest”. “I was like, ‘you’re right’. So I went to the cast and I told them something I don’t tell people, like, _ever _– I grew up not telling people it – which is that I’ve only met my biological father once. And the father that I generally speak about is a sort of fabulation, or amalgamation, of multiple stepfathers I had along the way. That’s been my way of doing it since I was in fifth grade, you know?” He promptly rewrote it all to reflect this. And did the exorcism work? “Mmmhmm. Absolutely.”

As for Slave Play, it casts a sharp light on a childhood spent among wealthier white friends, in a culture where he wasn’t taught to value being black or queer. Only a few years ago, Mr Harris wrote an article about learning to “de-colonise his desire”. Is his writing therapeutic, then? “I don’t think it’s therapy – it’s just the only way I know how to write, you know?” He ponders it more. “I do like the ritual of cutting myself and bleeding out publicly. I think there is a shaman-like nature to good writers, and the great writers are inviting us to witness a ritual they have to do, in order to get to some honest place of spirituality.”

Mr Harris spent most of his teenage years wanting to be an actor, and he still acts now, sometimes. But studying drama at DePaul University in Chicago was a great disappointment. There seemed to be little space there for accommodating his singularities. “I talked about this a lot with Gwendoline Christie, actually,” he says (almost) casually. “Drama schools are notorious spaces for the mediocre to end up… the mediocre in our craft so often end up running these places, and running them with an eye towards mediocrity.” In trying to produce rote actors, he says, “they often really damage, or attempt to damage, some of the most special people. And I was one of those people as well.” However, he was able to survive “because I’ve always been someone who knew as many histories, or more histories, than the people in charge... So that was always my superpower.” Where did that superpower come from? “Umm – reading a lot?”

Fast-forward, and now Mr Harris is a “serious playwright”, or so it would seem. “No, not yet!” he says, vaguely alarmed. “I mean, I still post weird sex jokes on Twitter.” Likewise, he dismisses the idea that to be tagged as the “black queer saviour of theatre” is a burden.

“It would only be burdensome if I didn’t wanna be those things, you know? Because I feel like there’s no limit to what being black or queer can produce. It actually is, for me, a marker, in that I’m in a lineage of historically bomb artists. The black artists I can think of, the queer artists, all do things that I’m more excited about than almost any other type of artist. So I feel like I need to own being in a club that’s really hard to get into.” And of course, by now it’s clear he is in said club. The only question, really, is when he gets cordoned off for good behind the VIP area.