THE JOURNAL

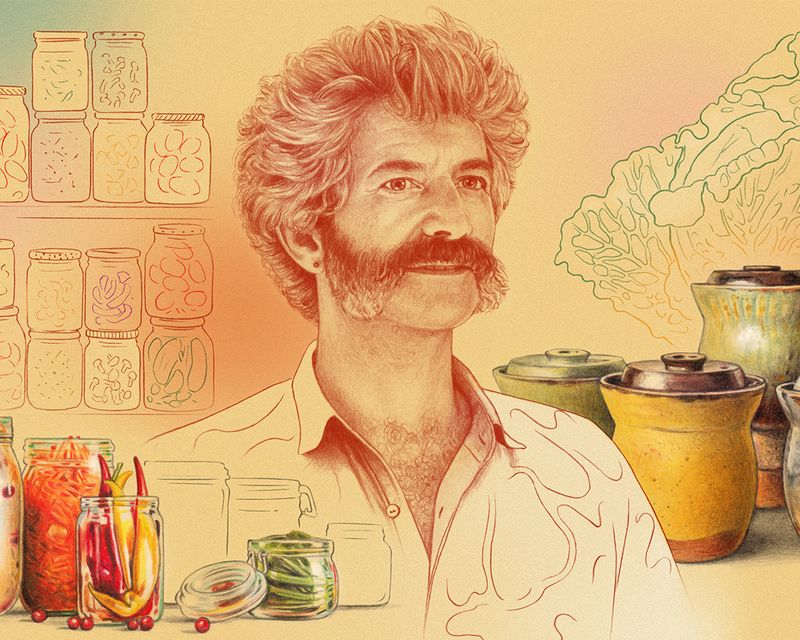

Illustration by Ms Oriana Fenwick

Fermentation has become a lot more fashionable in recent years. Beer, wine, chocolate and cheese were always pretty popular, but suddenly everyone was making their own ferments at home. During the pandemic, what the heck else did we have to do? Pickling jars and crockpots became all the rage. Sourdough trended. We discovered how certain ferments, eaten or drunk raw, not only tasted great, but were packed with potentially beneficial bacteria. And if the microorganisms involved – yeast, mould, bacteria – made us a little nervous, we could turn for guidance to Mr Sandor Katz.

Nicknamed the godfather of fermentation and Sandorkraut (after his love for pickled cabbage), Katz is the man behind the bestselling books Wild Fermentation and The Art Of Fermentation. Along with dispensing advice on how to produce yoghurt that keeps its consistency generation after generation (use an heirloom culture) and how to get a better rise on your sourdough (use a smaller amount of starter and a larger amount of water and flour), the Tennessee-based food writer and queer activist says he spends much of his time “just reassuring people about the safety of fermentation”. As the 59-year-old points out, fermentation produces acids, alcohol and other products that prevent pathogens from growing. In other words, just relax.

His latest book, Sandor Katz’s Fermentation Journeys, draws on 40 years of travel and goes beyond kombucha and kefir to celebrate some of the world’s other funky ferments. Here are some of his favourites to get the tastebuds quivering.

01.

Natto from Japan

“I love natto and I love the Japanese way of eating it,” says Katz of the sticky soybean ferment, which is often eaten heaped onto rice with a runny egg on top to emphasise its luxuriantly slimy texture. Westerners tend to be squeamish about natto, which is fermented with Bacillus subtilis, because of its mucilaginous consistency and strong funky flavour, which is likened to old brie. But thanks to its health benefits – it’s a rich source of vitamin K2 and associated with good circulation – natto extract is common in health food shops around the world.

Outside Japan, you can find dried natto-like seasonings such as tua nao in Myanmar and akhuni in Nagaland, India. In Japan, the slimy delicacy shows up everywhere. Katz once had it wrapped in a mochi (a doughnut-shaped glutinous rice ball) as part of the mochitsuki ceremony to bring prosperity at New Year.

02.

Pulque and mezcal from Mexico

A delicious, milky white, slightly viscous, tart, effervescent, low-alcohol beverage, pulque is made from the fresh sap (aguamiel) of the agave plant in Mexico. Because pulque ferments so rapidly – “You go to sleep, wake up the next day and it’s vinegar,” says Katz – you can only really find it in Mexico. More common elsewhere is mezcal, a strong, clear, distilled alcohol with deep, complex flavours, made from the pine cone-shaped heart of the agave plant (la piña). This is pit-roasted, crushed into pulp, mixed with water, allowed to ferment in wooden vats, then distilled. (Tequila is also made from la piña, but is the product of one agave species, Agave tequilana Weber, instead of many, like mezcal.)

Mezcal can be found on bar menus around the world, but among the best is KOL Mezcaleria in London, where an extensive list of mezcals sits alongside other Mexican distillates, such as Sotol, made from a relative of the agave plant called dasylirion or “dessert spoon”, and pox, a centuries-old liquor produced from corn, wheat and sugarcane by the Mayans of Chiapas.

03.

Tarhana from Turkey

The original instant powdered soup, this versatile Turkish food is made from wheat mixed with yoghurt (like Lebanese kishk), plus legumes, vegetables, herbs and even fruit. The cooked vegetables are typically mixed with flour, yoghurt and salt, turned into a dough, allowed to ferment for one to two weeks with daily kneading, then shaped into discs, dried and crumbled. This can be stirred into boiling water to make broth or added as a flavoursome thickener to sauces.

Tarhana comes in a range of colours and flavours, depending on which vegetables or herbs are used. Katz makes one with tomato and okra. Acclaimed chef Mr Fatih Tutak produces more than 20 at his restaurant Turk By Fatih Tutak in Istanbul, including one wild mushroom tarhana with porcini and chantarelle. Among the countless shop-bought versions, Tutak recommends a traditional tarhana by Havsa Kadin Kooperatifi.

04.

Iru from Nigeria

A foundational ingredient in west African cooking, iru (the Yoruba name for fermented African locust bean) is used to flavour stews, soups, meats and vegetables. It is also known as dawadawa, ogiri, afiti, sounbareh and netetou. Katz raves about the “deep funk” produced by the Bacillus subtilis bacteria, which is also present in natto and recalls the ripe whiff of camembert. The process of making iru involves shelling the pods, then boiling, hulling, fermenting and drying the seeds. As Katz points out, this traditional seasoning is increasingly displaced by cheaper, factory-produced condiments, such as bouillon cubes or Maggi, a point of contention for Nigerian-born chef-activists such as Mr Tunde Wey, who produces and sells iru at disappearingcondiments.com.

You can find iru in everything from egusi soup (made from ground melon seed with fish or meat) to efo riro (spinach stew). Chef Mr Theo Clench of Akoko in London also uses the ingredient as a glaze in his barbecued quail yassa and in a caramelised agege (a sweet Nigerian bread), grilled pineapple and iru ice cream dessert.

05.

Doubanjiang from China

Used widely in Sichuanese cooking, this seasoning fermented from broad beans and chillies brings umami and heat (“chilli meets miso” is how Katz puts it) to any dish. The four-step process of making doubanjiang, which is also known as chilli bean paste or Pixian chilli paste after the city where it originates, involves growing fungus on broad beans, brining the fungus-covered beans, fermenting salted chillies, then mixing everything together to ferment, being sure to expose everything to sunlight to facilitate evaporation and concentrate the flavour.

Doubanjiang can be fermented for anything between one year and many years, with young batches bright red and very hot and older batches a duller brown-red and much earthier. Katz uses it in stir-fries, adding it to hot oil with onions and garlic at the beginning. According to food writer Ms Fuchsia Dunlop, the best shop-bought version is Juan Cheng, though the most widely available brand is Lee Kum Kee Sichuan chilli bean sauce.

06.

Acarajé from Brazil

“As ferments go, this is about as easy as it gets to make,” says Katz of the Afro-Brazilian fried fritters made from a batter of black-eyed peas and onions. The process involves soaking the peas in water, blending with onion, salt and pepper until a smooth paste, fermenting for a day (“or several” says Katz), then deep- or pan-frying.

The acarajé-makers Katz encountered in Brazil, he notes, weren’t deliberately fermenting their batter. The tropical heat in Brazil means the batter inevitably starts to ferment after a few hours, but to Katz’s mind, a deliberately longer ferment (maybe eight hours in summer and up to 36 hours in winter in a western climate) allows the batter to rise and results in a lighter, more flavourful fritter. In Brazil, the acarajé is typically served hot and crispy as a vehicle for a shrimp, coconut and nut paste known as vatapeá, which every cook has their own version of.