THE JOURNAL

From left: IWC and Porsche Design, Titanium Chronograph 01, 1981; IWCDa VinciCeramic lime green prototype (never entered series production), 1987-1988; IWC and Porsche Design, Compass Watch with Moonphase, 1985. All photographs courtesy of IWCCorporate Archives

I can remember the first time I saw one of these crazy watches as if it were yesterday. I was hosting a panel event on the future of digital in watchmaking and one of my guests, the Danish watch collector, writer, photographer and industry insider Mr Kristian Haagen showed up wearing not one, but two IWC Schaffhausen watches. On one wrist, a slow beat IWC Big Pilot 5002, the original Big Pilot, in steel from 2002. On the other was a bizarre, organic looking creature on a Velcro strap that I had never seen before. It was an IWC/Porsche Design Ocean 2000, one of the most unusual and groundbreaking watches to come out of the 1980s and, although I didn’t know it at the time, the poster boy for an incredible era at IWC of collaboration and creativity across both design and technology. A period of success that’s all the more impressive given the general state of disarray in which the watch industry found itself at the start of that decade.

IWC and Porsche Design,advert from 1988 featuring the Ocean 2000 Divers watch first launched in 1982. Photograph courtesy of IWCCorporate Archives

Long story short, the 1980s era at IWC has become something of an obsession within an obsession for me. Four years on from that evening I am now the proud owner of three vintage IWCs (if my wife is reading this, it’s one vintage IWC). By the end of that decade, IWC had mastered collaborations between luxury brands, become an industry leader in materials technology and started a programme of extremely high-end watchmaking that produced some legendarily complicated models.

In essence, everything that modern brands strive to achieve, IWC had it nailed 40 years ago – and yet is hardly ever celebrated for it outside niche collector circles.

“Focusing only on ultra-traditional watchmaking was not enough. There was a hunger to develop more modern and creative designs”

How IWC got here ahead of the competition is partly down to luck and coincidence, but also the individuals involved in creating a real melting pot of creativity at what was in all honesty a small, slightly obscure tool-watch maker on the Swiss-German border. In the mid-1970s, the high price of gold, a strong Swiss franc and the emergence of low-priced quartz watches had put the Swiss watch industry under enormous pressure. IWC, like others, had to be agile and innovative to survive.

First, and somewhat bizarrely, it looked to complicated pocket watches for mechanical watch connoisseurs for this edge and presented an annual calendar pocket watch at the 1977 Baselworld watch fair. This was a power play to show the watch world it was dedicated to the handcraft of traditional Swiss watchmaking. The watch sold out immediately and so assured IWC’s management that demand still existed for mechanical haute horlogerie. It was clear, however, that focusing only on this kind of ultra-traditional watchmaking was not enough. There was a hunger to develop more modern and creative designs.

In 1978, IWC was acquired by a German instrument manufacturer, VDO Adolf Schindling AG. The new owners brought the legendary Mr Günter Blümlein (later the driving force behind the revival of A. Lange & Söhne) on board, a qualified engineer who was also well versed in distribution and marketing.

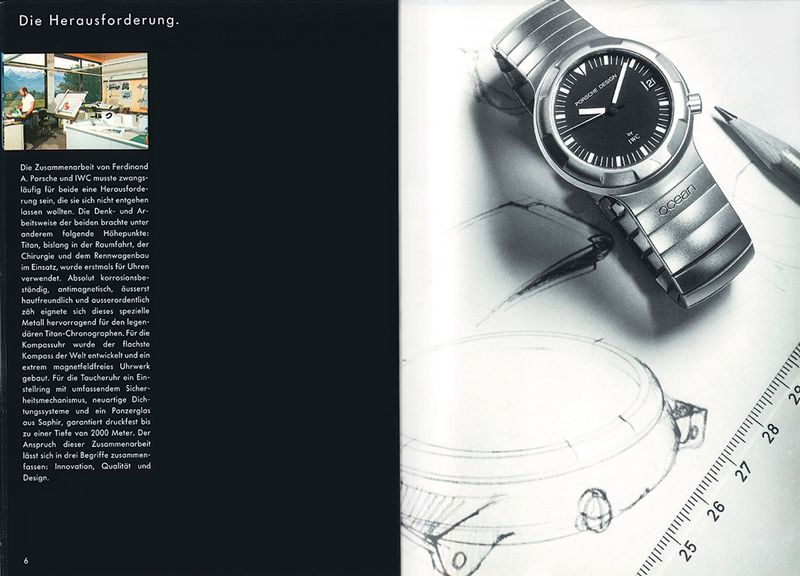

At the same time, FA Porsche, six years after it created Porsche Design as a standalone business, was looking for a watchmaking partner. Blümlein’s designs were much more than simple co-branded creations. Porsche was shopping around some really bold concepts, looking to create watches along entirely new lines. It was just what IWC needed to attract a younger, forward-looking audience, but it also brought significant technical challenges.

“It was widely believed that zirconium dioxide was the material of the future and so revolutionary that nobody could think of all the possibilities to use this material”

The first piece from the partnership laid down a technical landmark in the art of watchmaking. The 1978 Porsche Design compass watch (a watch I own and love) comprised a double-decker watch case, hinged at one side, which flipped up to reveal a compass.

To ensure the compass worked properly, the case and bracelet, with its adjustable clasp, were made of aluminium and then the surface was hard-anodised. The compass, developed in house by IWC, was fitted with a sensitive needle protected against impacts on both sides. All parts of the automatic movement that could have an adverse effect on the workings of the compass were made of antimagnetic material and the watch resulted in no fewer than six new patents.

IWC and Porsche Design, Compass Watch with Moonphase, 1985. Photograph courtesy of IWCCorporate Archives

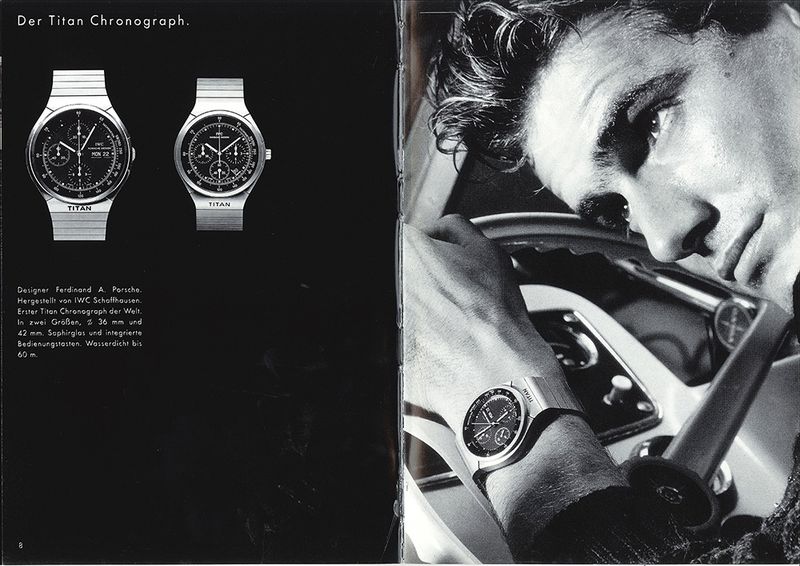

Not content with that, Porsche Design and IWC pressed ahead to break more conventions. FA Porsche’s vision was for a fully titanium-cased watch, something that had never been done before. IWC found a supplier that claimed it could deliver, but after 18 months of trying and just three months ahead of the launch date, it pulled out. The watchmaker’s engineers were left with no choice but to take on the challenge themselves and, gleaning as much as they could from the aerospace industry, managed to create the cases (including a polished finish, thought to be impossible to achieve in titanium).

In 1980, it launched the titanium-cased Porsche Design chronograph and followed it up two years later with the Ocean 2000, a design that managed to combine sleek proportions with a phenomenal 2,000m water resistance rating and the kind of quintessentially 1980s lines that would catch my eye some 36 years later. To me, the Ocean 2000 was the perfect marriage of IWC’s toolish design and craftsmanship with the adventurousness of Porsche Design.

All of which is very well, but crucially the Porsche Design watches were as popular as they were unusual. In the eyes of some collectors, it might even be said that the Porsche Design partnership saved the brand.

IWC archivist Dr David Seyffer says, with a bit more restraint, that “the Porsche Design watches by IWC were very successful. Back in those days it was maybe the best performing sports watch. There was the Ingenieur and Yacht Club II models in the 1980s at IWC, but the whole Porsche Design family was something completely new and therefore very popular.”

IWC and Porsche Design, advert from 1988 featuring the Titanium Chronograph 01, 1988. Photograph courtesy of IWCCorporate Archives

While IWC was developing a proficiency with titanium watchmaking, another strand of material innovation was also coming to the fore. In 1975, the British physicist Mr Ron Garvie, who was employed at the Australian research institute CSIRO, together with Messrs RH Hannink and RT Pascoe, published a short one-and-a-half-page paper entitled “Ceramic Steel?” in the journal Nature. It caught the attention of materials researchers worldwide.

“It was widely believed that zirconium dioxide was the material of the future and so revolutionary that nobody could think of all the possibilities to use this material,” says Seyffer.

It was immediately apparent that ceramic could provide scratch-proof watch cases, which would be a huge step forward. As luck would have it, in 1978 a specialist ceramic manufacturer by the name of Metoxit AG was founded only a couple of miles from Schaffhausen, producing mainly medical implants. IWC had its supplier. Now the question was how that material could fit into its portfolio.

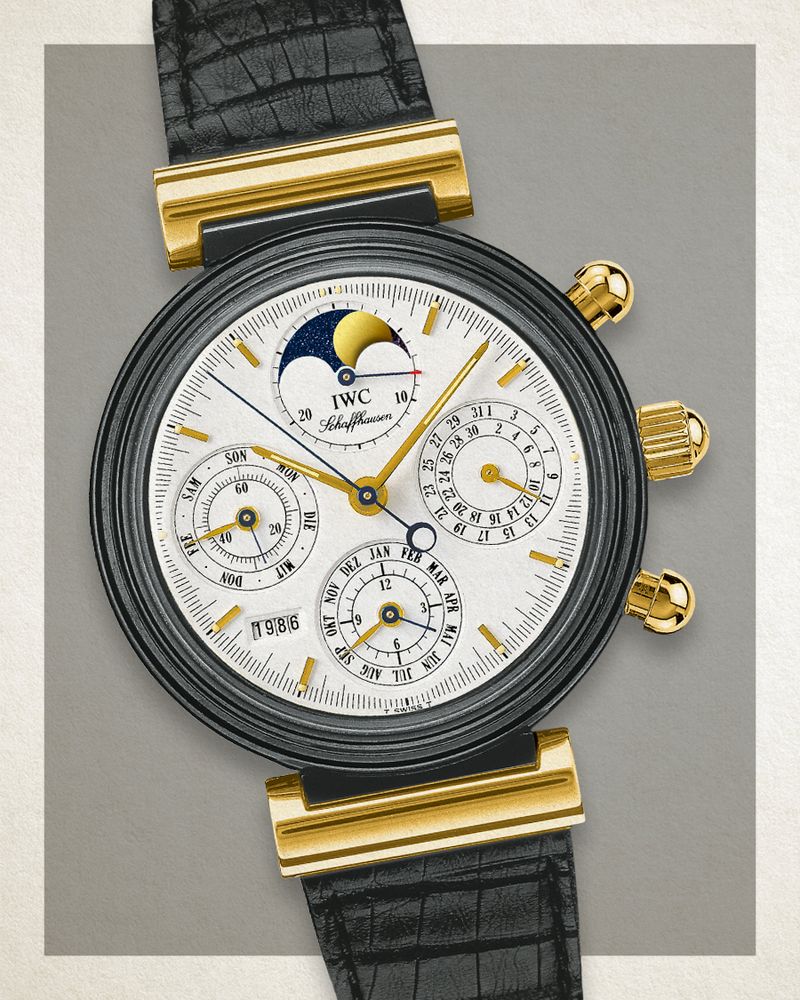

IWCDa VinciCeramic Perpetual Calendar, 1986. Photograph courtesy of IWCCorporate Archives

It was a few years yet before the first ceramic watch appeared. Rather than deploy it in one of its simple tool watches, IWC took an unusual decision. It had enjoyed huge success with the launch of the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar in 1985, a groundbreaking watch in itself, which boasted a new perpetual calendar movement that for the first time was completely adjustable by the crown. Created by celebrated watchmaker Mr Kurt Klaus, it was another statement of intent for high-end watchmaking, but aesthetically was classical, with its stepped bezel and delicate lugs.

IWC decided to combine these two categories – the traditional perpetual calendar and the innovative high-tech case – and launched the Da Vinci with a ceramic case in 1986.

“It was the perfect shape for a ceramic case. In this round form the ceramic was just about unbreakable”

With the Porsche Design partnership thriving, the engineering genius of Klaus, the business clout of Blümlein and the material competency to make both titanium and ceramic watches, the stage was set for IWC’s 1990s revival and the reintroduction of the Pilots watches and Portugieser models for which it’s best known today (neither existed in the 1980s, believe it or not). But there is one more chapter in IWC’s 1980s story that bears inclusion, for the end results are rare, unusual and ahead of their time.

Today, Louis Vuitton makes a wide range of watches, from award-winning dive watches (as worn by Mr Tahar Rahim recently) to intricate flying tourbillons and flashy smartwatches. In the 1980s, it had no watch business at all, but was keen to take its first steps. Since 1854, it had accompanied the world’s globetrotters, so the management thought adding a watch specially designed for travellers to its portfolio would be wise. It also seems they were keen on a ceramic case, which led them to IWC’s door.

Working with Porsche Design was one thing, but partnering up with a name such as Louis Vuitton would give IWC some serious prestige. A deal was struck in 1987. The supplier for the ceramic cases was once again Metoxit AG. Louis Vuitton initially wanted to market the watches exclusively in its own stores, but it was decided that “IWC” would be engraved on the back of the watch and included editorially in the product description.

Two watches were developed and manufactured by IWC for Louis Vuitton, which had enlisted the Italian architect Ms Gae Aulenti to design them. The watches were a quartz world timer, which ended up being produced not in ceramic but in 18ct gold and priced around CHF 10,000, called the Louis Vuitton LV-I World Timer, and an alarm watch, also quartz powered, in a ceramic case available in green and black called the Louis Vuitton Monterey II Alarm Travel Watch. They were typically abbreviated to LV-I and LV-II.

Aulenti’s design was a perfectly round case, not unlike a modern-day Ressence, with a crown at 12 o’clock. It was the perfect shape for a ceramic case. In this round form the ceramic was just about unbreakable.

The merger of Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy to form the LVMH Group in September 1987 brought about a change in management and the project was not pursued. Between 1988 and 1990, only a few of these watches were produced, which inadvertently creating that most modern of concepts, the luxury partnership limited edition. These timepieces are highly sought after by collectors with an interest in fashion history as well as watches and they remain incredibly unknown.

The 1980s were a pivotal time for the watch industry and one in which IWC transformed into a multi-faceted manufacturer with much broader experience than before. In doing so, it ended up resembling a watch brand from the 2020s, so the next time you coo over a limited-edition collaboration with a funky case material and guest designer, remember IWC got there first.