THE JOURNAL

The award-winning star of <i>Mary Magdalene</i> on the reasons he’s relishing the decade to come.

In his latest film, Mr Chiwetel Ejiofor plays the apostle Peter, dutifully accompanying Jesus to the cross. It sounds intense, but it’s small fry for Mr Ejiofor, 40, who has built a career out of challenging and weighty roles. From his Oscar-nominated turn as Mr Solomon Northup in Mr Steve McQueen’s 12 Years A Slave, through to playing such political figures as former South African president Mr Thabo Mbeki or the Congolese independence leader Mr Patrice Lumumba, even down to his cinema debut in Mr Steven Spielberg’s slave-ship drama Amistad, he rarely dabbles in the inconsequential. Over breakfast in west London, he shrugs off any pressure.

“A long time ago, I was filming Endgame, in South Africa,” he says. “I was playing Mbeki, and there, above my trailer, it said ‘THABO MBEKI’. I was like, eurgh, man. This is such a weight of responsibility.” As he stared at his trailer door, pondering all this, his co-star Mr Clarke Peters’ car rolled up to the trailer next door, which said “NELSON MANDELA”. “He just strode in,” says Mr Ejiofor. “And I thought, well, he seems OK with it. I felt from that point, you know what? It’s OK to just get on with it.”

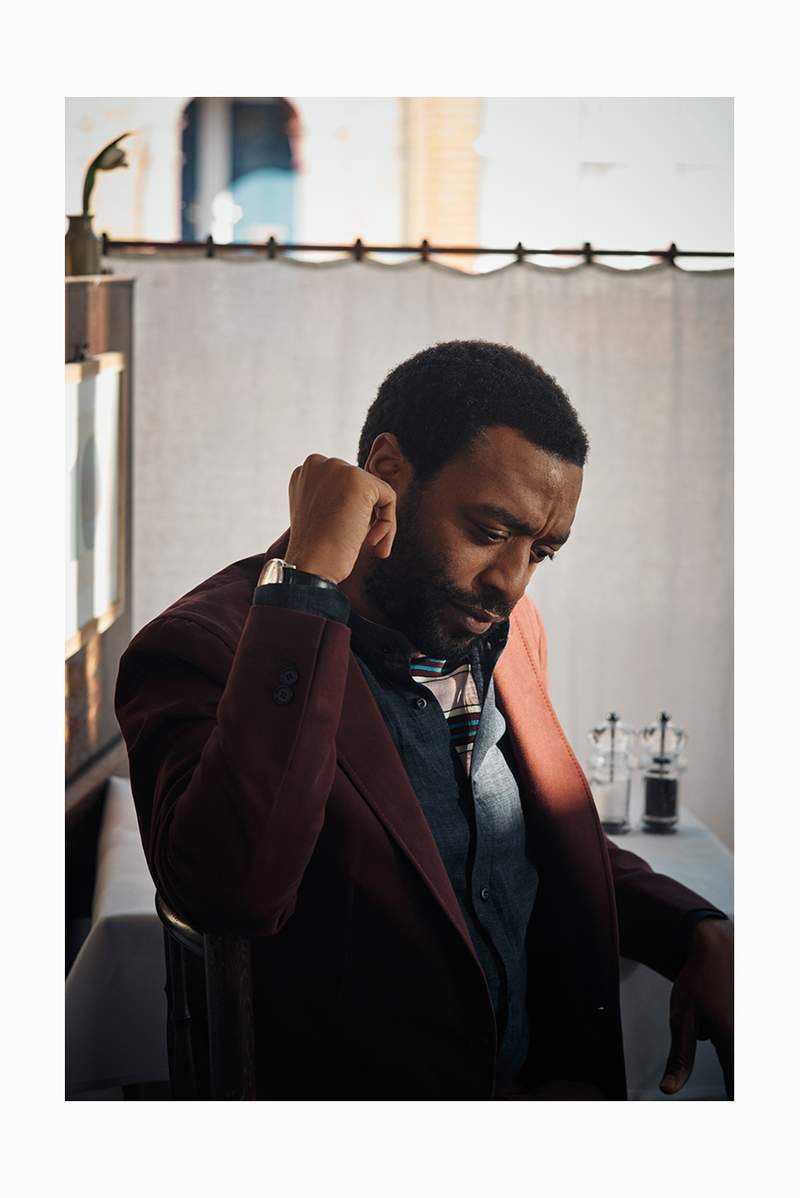

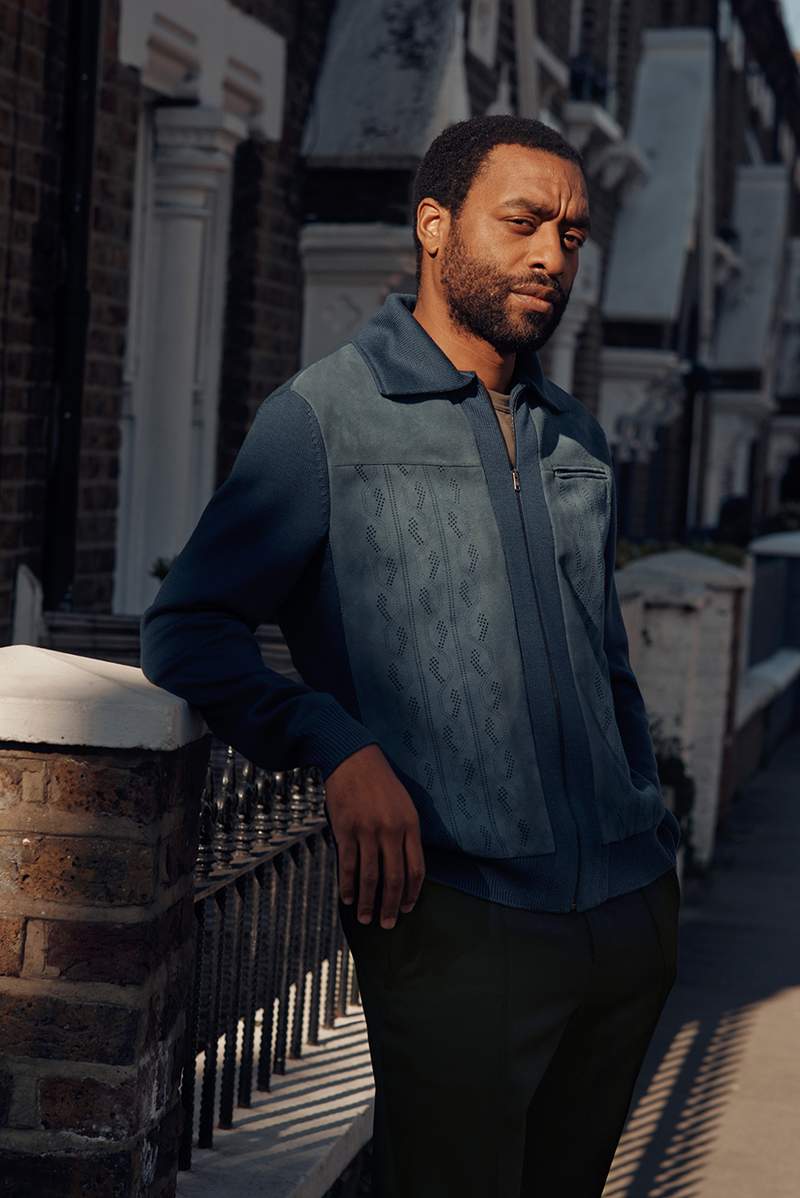

Total dedication mixed with common-sense can-do is Mr Ejiofor’s calling card, off-screen as well as on. Born in Forest Gate, east London, to Nigerian parents, he is one of the greatest British actors of his generation. He is also one of the least starry. He walks in to our interview punctually, at 10.00am on the dot (maybe even 9.59am), then neatly polishes off some scrambled eggs and salmon, with two coffees. He wears an indigo blue corduroy jacket, blue chinos and a pink-and-white striped grandad shirt, all topped off by solid, cerebral Wayfarer specs. He veers between formal and informal, but is always chatty and civil, speaking in fluent RP. In his spare time, he loves to sail, but don’t get the wrong idea. “I’m not really a deck shoes kind of sailor,” he says. “I’m still more trainers.”

We are meeting to discuss his latest film, Mary Magdalene, which tells the “true” story of the other Mary, for so long muddled by misinformation and misogyny. Ms Rooney Mara has the title role, Mr Joaquin Phoenix is Jesus and Mr Ejiofor, as previously mentioned, is Peter. Contrary to what you might think, however, the role isn’t totally saintly. Peter is anxious when Mary, a lost and lonely soul, decides to join Jesus and his band of followers. His attitude to her only hardens with time. Mr Ejiofor – and this is, it’s soon clear, a persistent trait – refuses to take sides easily, or to condemn.

“It doesn’t seem totally unreasonable, initially, for Peter to be worried about bringing Mary along, because, well, it doesn’t seem like the best way to spread a message, to carry off young girls with you,” he says. Dry understatement is another of Mr Ejiofor’s favoured modes. “But what it reveals is actually a whole set of beliefs and ideas that are taken as truth, about his and that society’s relationship to women.”

Before he was sent the script, Mr Ejiofor was – like many others – “in this whole other bubble of belief about Mary Magdalene”. Does he mean the traditional view of her as a prostitute? (A notion first advanced only in 591, by Pope Gregory I, it turns out.) “I was always inherently suspicious of, or dismissed, the prostitution angle,” he says. “It seemed a little far-fetched to me. But certainly, I didn’t think she was as significant as it turned out she was.” In 2016, Pope Francis explicitly confirmed Mary Magdalene Apostle Of The Apostles, on a par with Peter, John or the two Jameses. She is now central to the story of Jesus, and not just a bit player, as director Mr Garth Davis’ film makes clear. In short, it’s a story worth retelling, especially as, Mr Ejiofor insists, we can never look back enough at what happened some 2018 years ago, considering how much it still affects how we live and think today. “Religion is the fabric of our societies,” he says. “We can’t really claim this secular identity with any real, robust energy.”

Mr Ejiofor himself had a Catholic upbringing, but it wasn’t particularly strict. “It was just something to do with Christmas,” he says. “Broad strokes. No deep dives.” Ask him if he has any belief now, and he gives a typically roundabout answer – “I don’t think I have, at this point in my life, any structured religious direction in terms of organised faith” – which is a well-considered way of saying “no”. He is generally not keen on giving biographical facts away. There are no rings on his fingers, and when asked if he’d like children, he says simply, “We’ll leave it up to life to decide.”

What we do know is that he became passionate about acting as a teenager. His father was a musician and a doctor, his mother ran a pharmacy and he has three siblings. What is also often repeated is that he was in the car crash that killed his father, en route to a wedding, when the latter was 39 and the young Chiwetel was 11. A long, thin scar snakes faintly down the side of his forehead. He is often asked to revisit the accident. It seems kinder to ask something jollier. Is it true his father was a pop star in Africa?

“He was a reasonably well-known musician in Nigeria,” he says cautiously. Is that a nice thing to remember him by? “Well, both his jobs are.” Asked about his own musical tastes, Mr Ejiofor replies that they are “eclectic”. Asked about the last gig he attended, he admits it was seeing Mr Paul Simon perform in Los Angeles. His father loved Mr Simon’s Graceland album.

“I was very, very keen to go because one of my first memories, when I was very young, was my parents coming back from a Paul Simon concert,” he says. “I realised that I was about the same age as my father was when he came back from it. So, I thought it was quite fun to go at that same age, at a generation removed.” He is, of course, now, a year older than his father ever was.

Turning 40, he says, is nice. “Somewhere, in my late twenties or early thirties, I lost track of where one was supposed to be doing what, in the grand scheme of life,” he says. “And then you’re just existing, and doing your thing, as and when you want.” He thinks he is still too close to his thirties to be able to reflect on them, but he has, “for a long time, enjoyed not being in my twenties any more. Because that was such a bizarre time, just trying to fit everything together and construct a person.”

In contrast, the coming decade, between 40 and 50, looks good. “It’s a fascinating age, potentially the most interesting age to be,” he says. “It feels like you’re right at the beginning of the most important part of your life.” This even applies to his sense of style, which he admits is still a work in progress. “I think I’m maybe still in a very nascent, early development stage,” he says. When he’s sent a suit for an awards ceremony, he “has questions”. “But like I say, I hope to continue in that vein, to further discover myself. That’s why it could be my decade.”

Mr Ejiofor does do more jovial fare. He will soon be providing a voice for the cartoon caper Sherlock Gnomes (as Gnome Watson), and next year there’s another voiceover in Disney’s remake of The Lion King, in which he plays the horrible uncle, Scar. “He’s such a baddie, as well,” he says with measured glee. “I don’t think you could get away with a baddie like that if it was made now. It’s outrageous.” There has always been some glitz among the grit, not least his turn as a thigh-high-booted drag queen Lola, aka Simon, in Kinky Boots. True to form, he insists that this, too, had a serious message, about diversity and acceptance. “I think comedy, or light entertainment, should be that,” he says. “It should be really telling you something. All entertainment should have a point.”

Ask Mr Ejiofor which roles he took just for the money, and he looks quite blank. “That’s not really what acting ever was for me, and I don’t know how to make it that,” he says. “It was always a way of exploring some other question, some deeper question about myself.” Has he found many answers? “I’ve just found more questions,” he says with a smile. Expect another weighty decade.

Mary Magdalene is out now