THE JOURNAL

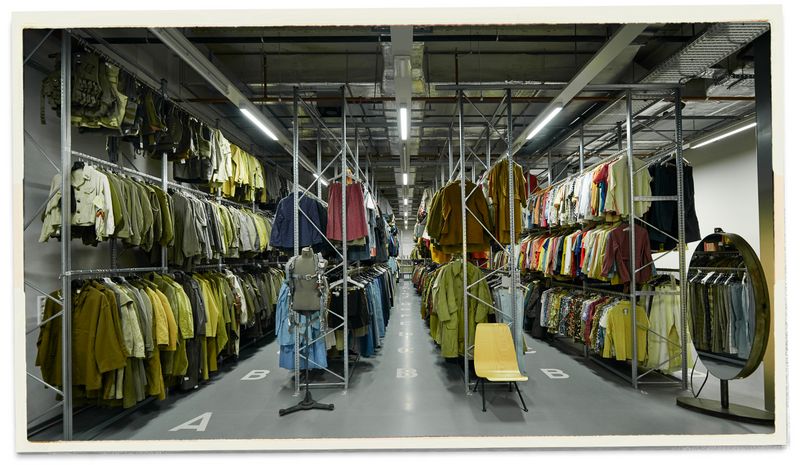

The Vintage Showroom, London. Photograph courtesy of The Vintage Showroom

The inside story of the vintage clothing collections that are inspiring today’s designers.

“I’d have to say my favourite piece is a Special Boat Service canoe smock,” says Mr Doug Gunn. “It’s just so rare. I’ve only ever seen that one – and the one in the Imperial War Museum, of course.”

If there were an area of the Imperial War Museum devoted entirely to 20th-century military clothing, there’s a good chance it would look like the interior of Mr Gunn’s warehouse in west London. This is home to The Vintage Showroom, one of the world’s leading menswear archives, specialising in workwear and militaria, established by Mr Gunn and his business partner, Mr Roy Luckett.

The space is full of the kind of garments that make historic menswear fanatics salivate. This is the stuff you can’t find on eBay, ever. “It’s a way of bringing together those clothes that have amazing design details that their functional use dictated,” says Mr Gunn. “These were garments designed expressly for purpose and, in the military’s case, often with unlimited budgets behind them.”

Messrs Gunn and Luckett have not pulled this collection of tens of thousands of incredible pieces together for the love of it, however – though they clearly do love it. Their warehouse is a resource, visited by researchers and fashion designers, and the occasional extremely serious, extremely loaded collector, all of whom are looking for knowledge and inspiration. Fashion companies might buy a piece, rent one – for anywhere between a week and a year, with several hundred out on loan at any time – or just take photos or make a sketch for a tidy licence fee. Anyone else who visits? Don’t expect to be able to get your phone out for some personal snaps.

The Vintage Showroom, London. Photograph courtesy of The Vintage Showroom

“Designers see a garment and that sparks off a thought process that can lead to an entire collection,” says Mr Gunn. “And sometimes you just see a very literal interpretation of the garment turn up in a collection. The fact is that recent years have seen a new appreciation for the design standards set by much workwear and military clothing, especially as men have started to dress more casually. We find that even really high-end luxury brands are drawn to the aesthetic now.”

The Vintage Collection is not the only player in this business. Around the world there are similar archive businesses servicing the growing demand for inspiration. Some of the bigger and especially the more historic brands, such as Ralph Lauren, Belstaff and Levi’s, or more deliberately military-inspired brands, such as Nigel Cabourn, have their own private archives. Perhaps unexpectedly, even the Dutch denim brand G-Star has an impressive one.

The G-Star archive, Amsterdam. Photograph courtesy of the G-Star archive

But beyond these, if a designer needs some ideas, they will often turn to the likes of Brut Clothing in Paris, or to specialists such as Mr Brit Eaton in Colorado, or Mr Ruedi Karrer in Switzerland, both of whom focus on denim garments. Mr Karrer has some 12,000 denim pieces and counting, but he is a man who literally measures his life in pairs of jeans. “I estimate that I have 10 to 15 pairs of raw jeans left in my lifespan,” he says. “I don’t think there is much chance of getting through 20 pairs. And the older I get, the slower I will move around, to the point where there may be no fading evolution at all. That’s a big dilemma for me.”

Mr Matt Breuer and his partner Mr Paul Dawson run Margate-based Breuer & Dawson, an archive that caters to the fashion and film worlds with many workwear and military-style pieces, but is expanding into more esoteric items. One recent find was a 1970s club-singer’s suit of a certain provenance. “The future of this business is always to be able to look beyond your own taste and what you might wear yourself,” says Mr Breuer, who favours original pieces from the 1930s and 1940s. Like The Vintage Showroom, Breuer & Dawson also operates a shop to sell still desirable but more mainstream pieces to the public. “You have to get excited more by the things that you’ve never seen before because that’s what people who use the archive want to see, too,” he says.

The Breuer & Dawson archive. Photograph by Mr Ollie Harrop, courtesy of Breuer & Dawson

All of which leads to what might be the million-dollar question or perhaps, after a pair of vintage Levi’s that sold at auction this year, the $100,000 question: just where do these archivists find the clothing? Unsurprisingly, they are vague about the process. There’s an element of pot luck, according to Mr Breuer. “You’d think the best things come through dealers we know, but often they just seem to pop up,” he says. “Someone comes through the door with a bin bag full of stuff and there at the bottom…”

“I’ve found old denim stuffed into sofas, used as padding inside a boxing bag, inside mannequins, scarecrows,” says Mr Eaton, who spends a lot of time visiting ghost towns and crawling around barn roof spaces. “You find stuff in crazy ways when you start looking.”

One thing they don’t do is buy consignment bales (bales of old clothes, bought by weight) in the hope of finding gold amid the dross, says Mr Gunn, who also archives Americana, vintage tailoring and knitwear. He admits to spending the occasional small fortune on pieces just to fill a gap in his collection, even when he knows it has limited commercial value to the company. “You have to keep constantly moving. We travel a lot. We have a network of people around the world whom we know we can go to if we’re looking for certain things. And sometimes we have collectors approach us who are looking to sell certain items. The problem with it all is that the more vintage clothing you see, the more you want to upgrade your collection. You want ever rarer, more special pieces.”

The Brut Clothing archives. Photograph by Mr Fabien Voileau, courtesy of Brut Clothing

Picking those special pieces takes the right eye, or the right training. Mr Paul Ben Chemhoun, founder of Brut Clothing, learned at his father’s knee. His father would buy huge quantities of military surplus and he would be charged with picking out the older, WWII-era pieces. He was 12 at the time. “Demand keeps shifting now though,” says Mr Ben Chemhoun, who admits to preferring a more preppy style for himself. “When I started selling a lot of French workwear, nobody really wanted it. Now it’s hard to get enough, for the Japanese market in particular. And, to be honest, it is getting harder to find really good stuff. And I expect it will only get harder.”

Awareness has grown exponentially. A decade ago, there was more vintage clothing to be found, but there was also more wastage. People didn’t understand what they had and threw it away. Now there’s much more knowledge, and so more competition. “Certainly, there are some pieces we sold early on in the business that now I wish we hadn’t,” says Mr Gunn. “I’ve even tried to buy some of them back, but that’s not so easy now. We have to keep finding new things to show our customers. In this business, you have to stay ahead of the game.”