THE JOURNAL

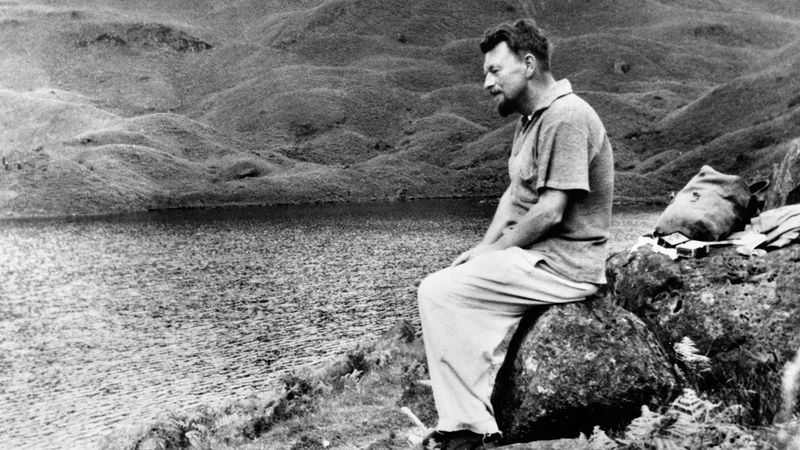

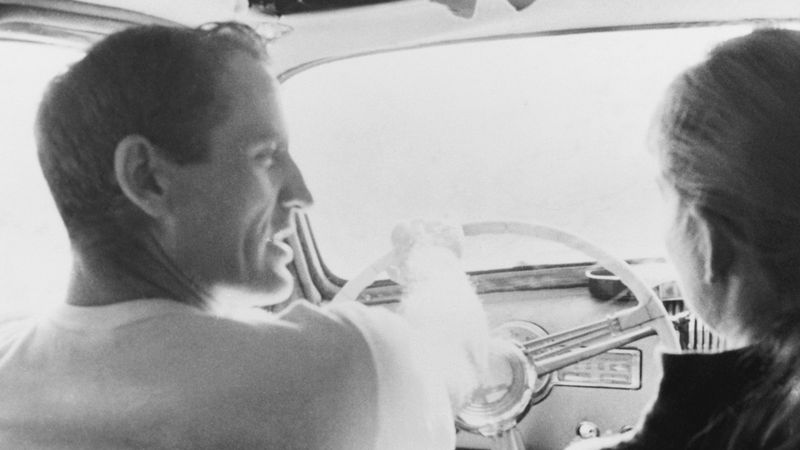

Mr Malcolm Lowry in a scene from the film Volcano: An Inquiry into the Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry, 1976. Photograph by Mr John Springer Collection/Corbis via Getty Images

From Mr George Orwell to Mr Marcel Proust – the men who embraced exile.

History is ripe with men who turned their backs on convention to create works of genius. The hermit in the cave, the poet in the garret, the mumbling vagrant with a mind full of verse – they capture our imagination most when modern life demands conformity. As we go about our daily routines, we might feel envious of men who choose a different path, as lonely or uncomfortable as they sometimes seem. And for those who harbour intentions of writing a novel – and there are many of us among the ranks – an avant-garde existence seems even more appealing, given the iconic authors who have lived such a life.

The most famous such man to embrace establishment exile is Mr Henry David Thoreau, who decamped to a hut in the Massachusetts woods to write Walden, inspiring values of self-sufficiency in generations of Americans (although he neglected to mention the regular strolls to his mother’s house for cookies, something even the most dedicated prepper will relate to).

But does it always prove fruitful to avoid convention? We look at five more outsiders of the world of literature to discover more.

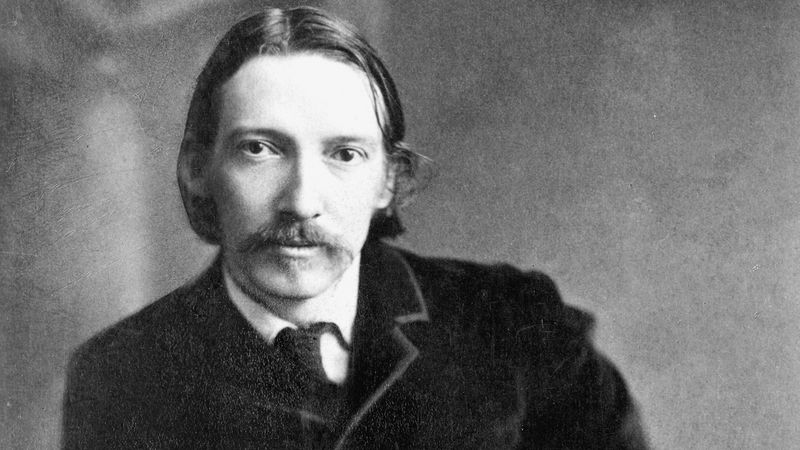

Mr Robert Louis Stevenson

Mr Robert Louis Stevenson, photographed in 1888. Photograph by Granger/REX/Shutterstock

Born into a family of means in Edinburgh’s buttoned-up New Town in 1850, Mr Robert Louis Stevenson was expected to follow a respectable path: his parents were strict Presbyterians, he read law at university, he was feeble with poor health. But rejecting destiny, he became a long-haired aesthete, thumbed his nose at religion, and frequented pubs and brothels in the city’s unbuttoned Old Town. He travelled, and how: tours of Europe, a canoe trip through Belgium and France, New York to California by train, and all the way to the South Seas, where he sailed, and where he died in Samoa, aged 44 and 9,000 miles from home. He lived like a character from one of his adventure novels: Kidnapped, Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde remain classics to this day.

The lesson: The expectations of upbringing are a burden. Cast them off and soar forth.

Mr Malcolm Lowry

Mr Malcolm Lowry in Dollarton, 1945. Photograph courtesy of the Malcolm Lowry Collection, University of British Columbia Library, Rare Books and Special Collections

Published biographies of Mr Malcolm Lowry: six. Published novels by Mr Malcolm Lowry: two. That speaks volumes about this literary enigma. One of his books, Under The Volcano, is considered a 20th-century lost classic, but his story is one of abandoned manuscripts and thwarted ambition. And destructive quantities of drink. Mr Lowry was an alcoholic who could have had Messrs Ernest Hemingway, Charles Bukowski and Dylan Thomas under the table before breakfast, but drink was both his animus and his nemesis: “You have many inspirations when drunk,” he said, “but then you must look at it with a cold, sober eye and most of it will be no good.” English by birth, he lived peripatetically, spending time in New York, Hollywood, Mexico and Canada, where he squatted in a beachfront shack north of Vancouver for years. His libatious lifestyle didn’t come without cost, however. He died in 1957 in Sussex, choking on his own vomit.

The lesson: Be careful where you seek your creative spirit: “Good wine is a good familiar creature, if it be well used,” as Mr William Shakespeare said.

Mr George Orwell

Mr George Orwell in front of a BBC microphone, 1943. Photograph by BBC Photos

Despite the grand sweep of Mr George Orwell’s life, which took in pot washing in Paris, policing in Burma, fighting fascists in Spain and selling books in Hampstead, he was a repressed man, his internal passion and his austerity constantly doing battle. Mr Orwell was a successful novelist by 1946, but couldn’t stand the concomitant celebrity; newly widowed, paranoid about Communist surveillance, despising bombed-out, busy London, he withdrew to Barnhill, a remote house in Jura, that windswept, wild island off the west coast of Scotland. It was cold and forlorn, requiring great economy and long trudges across snowy moors, but more importantly, it was conducive to work. In the barrenness of the Hebrides, he found great fecundity and produced his masterpiece, Nineteen Eighty-Four.

“Serious prose,” he wrote, “has to be composed in solitude.” Even today, Barnhill is not connected to the National Grid and relies on coal; if you’re serious about your own project, you can rent it yourself. Pack your thermals.

The lesson: Kill the distractions and watch your imagination flourish.

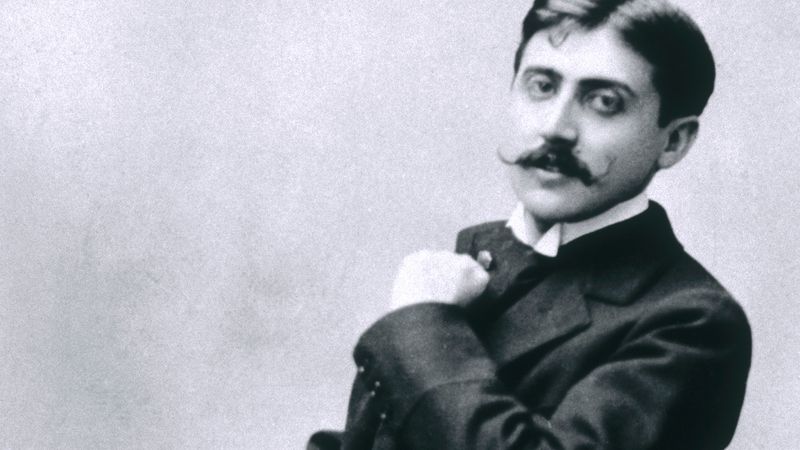

Mr Marcel Proust

Mr Marcel Proust, c. 1895. Photograph by Sygma via Getty Images

Some literary recluses crave the isolation of remoteness, disappearing into nature to tap reserves of primal creativity. Not so Mr Marcel Proust. Afflicted in later life by a sickliness that rendered him practically helpless, he largely spent the 14 years before death in 1922 tucked up in bed, missing most of the Parisian Belle Époque, with the curtains of his apartment in the 8th arrondissement drawn. He kept nocturnal hours, ventured out rarely, ate once a day, and complained about every aspect of being, claiming he existed “altogether between life and death”. But in his isolation he wrote In Search Of Lost Time, one of the greatest novels of the 20th century, which, over its epic seven books, implores us to recognise the past but not to let it cloud the present.

The lesson: Acknowledge adversity, live in the present, remember life is finite – and don’t stay in bed all day.

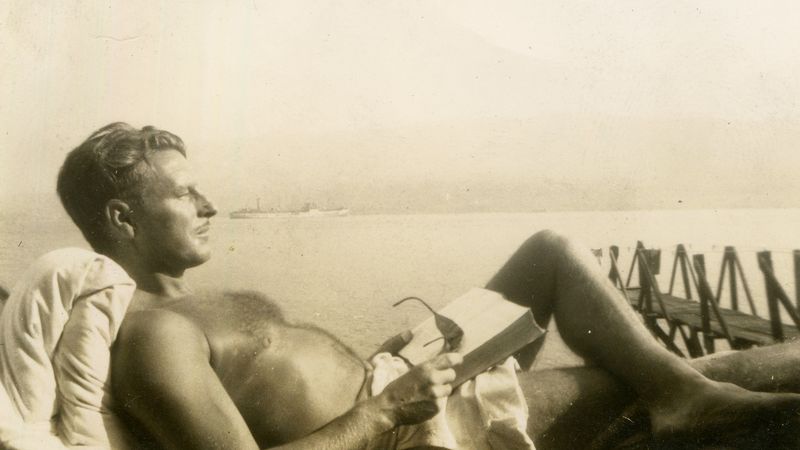

Mr Neal Cassady

Mr Neal Cassady. Photograph by Mr Allen Ginsberg/Corbis via Getty Images

He was Mr Jack Kerouac’s muse, a tireless Beat who drove the Merry Pranksters’ bus across the States gobbling any drug to hand. He was an artist who used life as his medium. He was a writer, the author of one novel and countless letters to friends, through which his oceanic well of energy exploded. He was a one-off, a man who lived the way everyone dreams of, at least sometimes.

But don’t be hard on yourself, as you lament your own monochrome existence while sitting on the 139 to Waterloo: he did it so you don’t have to. Sometimes, a little moderation is welcome. Mr Cassady wanted it all, all at once: to be a 1950s all-American dad as well as a no-rules outlaw. He died aged 41, frozen alone by a Mexican railroad, desperate of mind. He kicked the arse out of life but it got its revenge.

The lesson: Rebellion is often best enjoyed from a distance.

HIDE OUT

Keep up to date with The Daily by signing up to our weekly email roundup. Click here to update your email preferences