THE JOURNAL

The Stylist Behind Black Is King, A Groundbreaking Sculptor And Trailblazing Curator On Being Creative in 2020

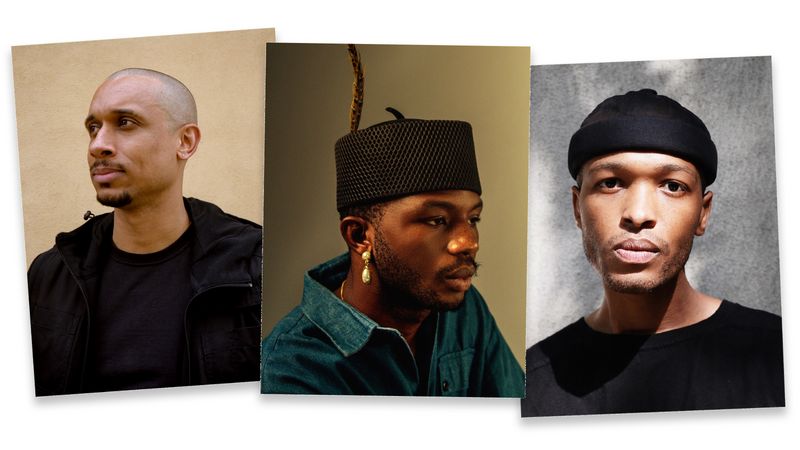

Left: Mr Thomas J Price. Photograph by Mr Ollie Adegboye, courtesy of Mr Thomas J Price. Middle: Mr Daniel Obasi Photograph by Mr Noma Osula, courtesy of Mr Daniel Obasi. Right: Mr Antwaun Sargent. Photograph by Mr Darius Garvin

The UK’s Black History Month isn’t the only time our contributions matter, but October serves as an annual checkpoint to celebrate what black creatives have brought to the cultural sphere. Across the visual arts, in fashion, food, music, media, photography and beyond, creatives are reflecting the world around us with beauty and intelligence. This has been a riotous year, one marked by continuous protest for black liberation and a pandemic that feels particularly precarious for artists. So, we decided to speak to a selection of creatives about a special project they have worked on. We asked them why they created their work and how they channelled their vision to highlight their experiences, aspirations and affection for their community.

Black Is King

Mr Daniel Obasi, stylist

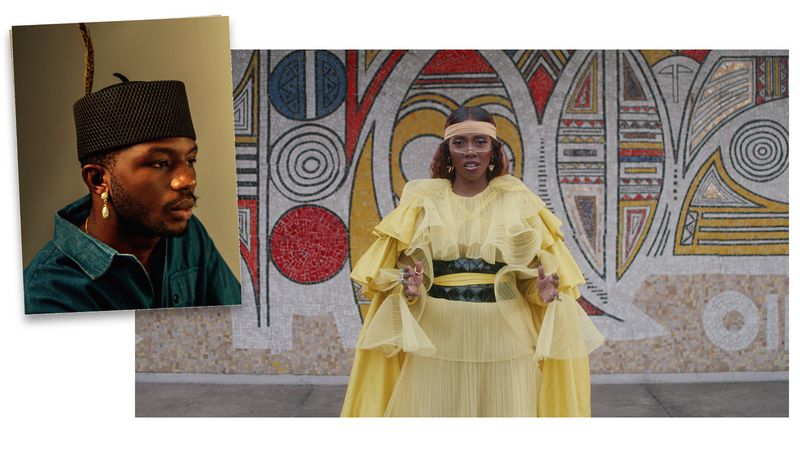

Ms Tiwa Savage in “Keys To The Kingdom”, Black Is King, 2020. Photograph by Parkwood Entertainment/Disney+

Lagos-based Mr Daniel Obasi, 25, has become one of the most sought-after curatorial eyes on Nigeria’s creative scene over the past couple of years and has produced work for publications such as Vogue, i-D and Dazed. He says he creates from “a happy place” to communicate what it is to be young, African and proud. It was only a matter of time before he got a DM from Mr Kwasi Fordjour, the co-director of Beyoncé’s Disney+ visual album Black Is King, which was released earlier this year.

You got the call to bring Beyoncé’s vision to life. Most people dream of something like that.

It was amazing. They asked if we were interested [in helping with the styling], then one thing led to another and the next day we’re shooting in Lagos. At the time, we didn’t even know what it was going to be called. It happened really fast. The magnitude of what we were working on didn’t even click until the project came out. It was great because it brought so many friends and people I respect across the industry together.

Which segments of the film feature your looks?

I worked on “Brown Skin Girl”, “Keys To the Kingdom” and “Water”.

Beyoncé wanted to use her platform to boost the profile of black people from places that don’t dominate pop culture in the way the US and the UK do. What were you trying to achieve?

The whole world is looking at Nigeria, now more than ever. You can see with the #EndSARS protests, there’s a lot of beauty and pain. I wouldn’t say we were exporting our culture, more that we are celebrating. Every day we make beautiful work and art is a way we inspire ourselves to live another day. For me, it was more about documenting and sharing some of the beauty from this part of the world through music, fashion and art and people who tirelessly believe in a Nigerian dream. The project taught us that our collective voices could combine to create something phenomenal.

Reaching Out

Mr Thomas J Price, sculptor

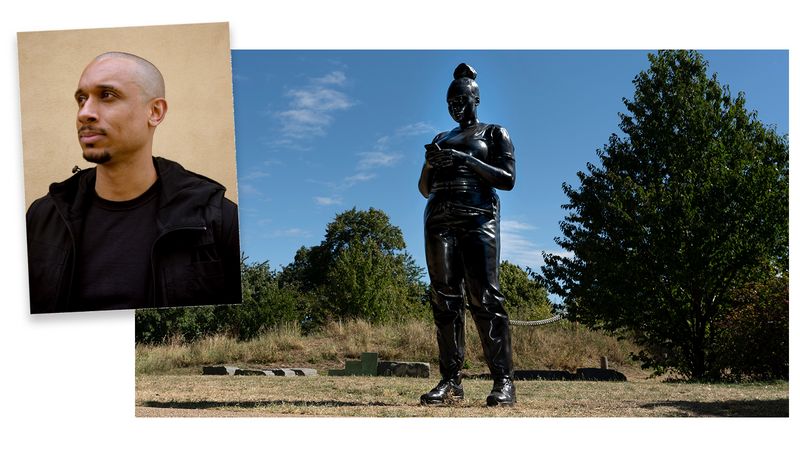

“Reaching Out”, London, 2020. Photograph by Mr Jeff Moore

Sculptor Mr Thomas J Price seeks to redress the racial imbalance of who gets to see themselves immortalised in bronze or stone. The 39-year-old Londoner’s latest work, “Reaching Out”, is now standing in Stratford, east London, where it forms part of The Line art trail. It is only the third statue of a black woman in the UK. Unlike Ms Jen Reid’s statue, which replaced Mr Edward Colston after the Black Lives Matter protests in Bristol this summer, or Ms Mary Seacole at St Thomas’ Hospital in London, the subject of Mr Price’s sculpture is not a famous or heroic figure. She simply represents an everyday black woman living her life.

Why did you create this statue?

It’s important that people feel recognised and valued within society. There was a complete lack of black women in public sculpture, even rarer for them to be made by black people. It’s a 9ft sculpture of a woman looking down at her phone. It’s natural, she’s engaged in something we all do and there’s a sense of vulnerability. It’s about being human.

Do you see your sculptures as levellers?

They’re a direct challenge to the imagery of power and the expectations of how power should be represented. I’m sculpting mostly black people because I’m looking at how they are perceived in society. Why are these figures not represented [in statues]?

Has the reaction to your work confirmed the need to create black figures?

When I first presented an image of a man in a puffer jacket holding a mobile phone [“Network”, 2013], it was deemed to be a representation of a rioter. Why are these figures controversial when they’re just people standing still? It became radical to present black people in a way that doesn’t placate society – like smiling or standing straight. They aren’t puffing out their chests in the expected stance of a sculpture. They’re not grand, conquering figures. They’re unguarded. They’re not looking for validation from the viewer and that gives them intrinsic power.

The New Black Vanguard

Mr Antwaun Sargent, writer and curator

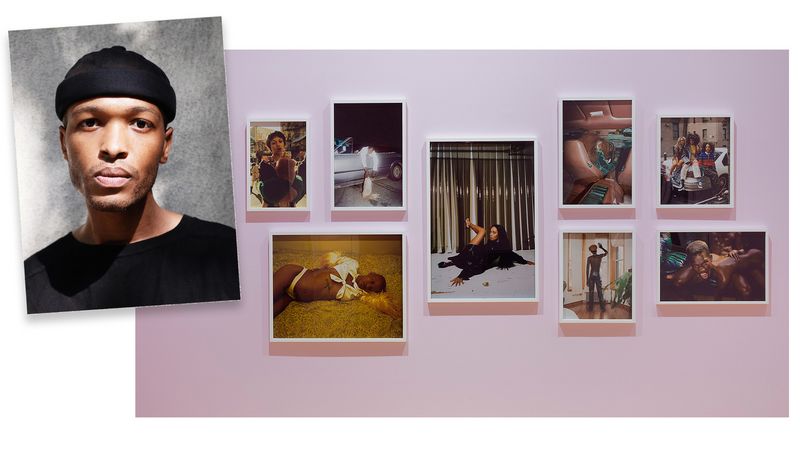

The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion, Melbourne, 2020. Photograph by Mr Christian Capurro

Writer and art critic Mr Antwaun Sargent, 32, has spent the past decade on a mission. He has travelled from his home in New York to the rest of the US, Africa, Europe and the Caribbean engaging with how blackness is presented in the visual arts. He has written on this topic for The New York Times, The New Yorker and Vice. In his book The New Black Vanguard, which was published in October 2019, he explores a movement of groundbreaking photographers creating a new contemporary aesthetic. Each of them invites a more inclusive approach to mainstream photography and collects Vogue, GQ and i-D covers in the process.

What makes a book that documents this cultural moment so urgent?

There are black photographers around the world using art and fashion to create their own language and renegotiate the black relationship to the camera and I just felt like you couldn’t ignore that. They each have a unique perspective. You can’t mistake a Micaiah Carter image for what Quil Lemons is doing or Tyler Mitchell’s work for Awol Erizku’s.

Do you see yourself as an archivist?

Magazine covers in 2020 have featured black subjects three times more than the previous 90 years. One could see that as progress or one could look and ask why now? Asking these questions opens really interesting debates around the black commercial image and the circulation of that. I do feel incredibly lucky to be able to witness and write the first book on this movement. These are young artists aged 22 to 35 at the beginning of their careers putting their perspective on a history that is unbelievably white, male and heterosexual.

What impact has the book had?

I have not seen a photobook garner this kind of reception in the past 10 years. It’s not even been out a year and it’s sold out four times. I think it signals to black photographers that their work matters. When we were on the book tour before Covid stopped us, people were coming from all over the place, flying from Seattle, travelling from Texas. There was a line down the block to see the exhibition. I saw people crying in front of photographs. I will never forget this for the rest of my life. This is what art can do.

Ms Kemi Alemoru is culture editor of gal-dem