THE JOURNAL

Hair Highway Vase, 2014 by Studio Swine for Pearl Lam Galleries. Photograph courtesy of Studio Swine

Good design,” says the German industrial designer Mr Dieter Rams, “is as little design as possible.” It’s a slippery statement from the old minimalist. We all know that to do something simple is inevitably harder and more expensive than doing something elaborate. Just look around. From cars to chandeliers, housing to furniture and signage, most of the things we live with are a mess.

But there is hope. These nine designers are standing up for intelligence and beauty, the rarest of characteristics. Even more than that, they manage to make design a kind of communication, a way of imbuing static objects with meaning that touches something in us. The path from Mr Rams to Apple’s Sir Jony Ive may appear straight, but we might also wonder where we go from here.

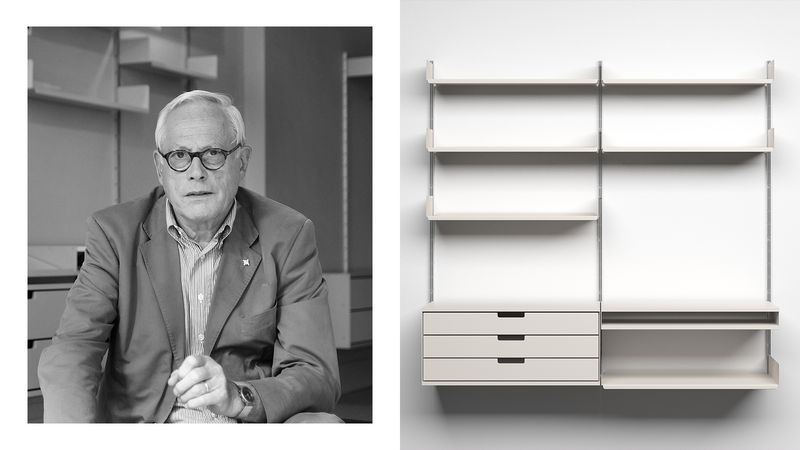

Mr Dieter Rams

Left: Mr Dieter Rams photographed at Vitsœ London, 2011 by Ms Anne Brassier, courtesy of Vitsœ. Right: 606 Universal Shelving System, 1960 for Vitsœ. Photograph courtesy of Vitsœ

The grand old man of modernism, Mr Dieter Rams is a direct link to the functionalist ideals of the Bauhaus. Educated at the Ulm School of Design (the successor to the Bauhaus in post-war Germany), Mr Rams made his name with his designs for German company Braun. The most famous of these was his SK4 record player, a minimal classic with a clear Perspex lid, white body and wood veneered sides, which led to it being dubbed Snow White’s coffin. For a piece of technology that is effectively defunct, it still looks remarkably cool and contemporary. He also designed everything from electric razors to lighters and calculators for Braun, each one still a beauty. Today, Mr Rams is just as well known for his 606 shelving for Vitsœ, a simple, wall-mounted system that, despite having been designed in 1960, is still the most modern thing around.

Ms Hella Jongerius

Left: Vlinder sofa, 2019. Photograph courtesy of Vitra. Right: Ms Hella Jongerius in Berlin, 2017. Photograph by Roel van Tour, courtesy of Design Museum London

“There is too much s*** design,” says Ms Hella Jongerius. The Dutch designer is outspoken in her critique of an industry that churns out new products just for the sake of it. Her take on design is to humanise products, reduce waste and export colour and she is known for mixing up a cocktail of traditional craft and modern technology. From new aeroplane seats for KLM to a redesign of the interior of the United Nations Delegates’ Lounge in New York and from Ikea to a computer keyboard with a dinner plate at its centre, her work covers every scale and type. Her tiles for Mutina make pleasing patterns, reminiscent of the seat on an old London bus.

Mr Oki Sato

Left: Mr Oki Sato, in his studio, Tokyo, 2018. Photograph by Mr Kento Mori, courtesy of Nendo. Right: Cabbage chair, 2008. Photograph by Mr Masayuki Hayashi, courtesy of Nendo

Founder of design firm Nendo, Mr Oki Sato has become one of the world’s most admired young designers. He manages to leaven the reductionist traditions of Japanese design with a lightness of touch and a depth of wit that give his objects an approachable, almost human familiarity. He took, for instance, the unremarkable elastic band, an item so familiar it has become virtually invisible, and turned it into a cube. The simplest of things become instantly perplexing and beautiful. For his Cabbage chair, he used a waste product – the tissue fashion designer Mr Issey Miyake uses between his famously pleated fabric – to create a seductively shaggy and characterful piece of furniture. But it is the qualities of his Fadeout chair that best display his quirky brand of minimalism. A very vanilla, functionalist design of skeletal form, the chair legs meld into a see-through material just before they meet the floor so that it appears to be floating. Exquisite.

Mr Jasper Morrison

Left: Glo Ball Floor lamp group, 1999 for Flos. Photograph courtesy of Mr Jasper Morrison. Right: Mr Jasper Morrison, 2016. Photograph by Ms Elena Mahugo, courtesy of Mr Jasper Morrison

In the early 2000s, Mr Jasper Morrison’s interest in the ordinary and the everyday set him apart from his contemporaries who were looking for ever wackier, more striking and more outlandish ways to grab the attention. Instead, Mr Morrison looked to the kind of products that were anonymous, almost invisible and yet so perfectly suited to their purpose that they could not be bettered. He outlined his ideas in an exhibition (curated with Mr Naoto Fukasawa, see below) and then a book, the tellingly titled Super Normal. His own designs have become almost ubiquitous themselves. The 1 Inch Aluminium Chair, the Low Pad and the Thinking Man’s Chairs have become cultural archetypes and his stripped-back MP02 phone for Punkt is an antidote to the overwhelming multi-functionality of the smartphone – and a throwback to Mr Rams. But just look at Mr Morrison’s Glo-Ball lights for Flos. More than 20 years old, but utterly timeless. Few designers manage to create products that just refuse to fade away.

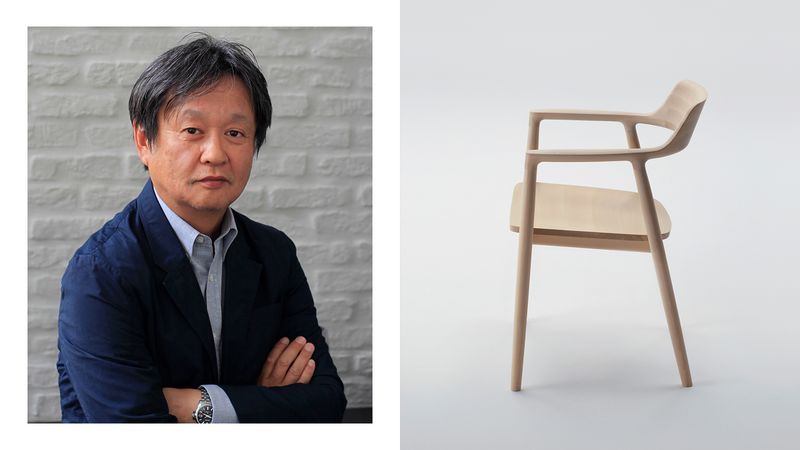

Mr Naoto Fukasawa

Left: Mr Naoto Fukasawa photographed in his Tokyo studio, 2012. Photograph courtesy of Naoto Fukasawa. Right: Hiroshima Armchair, 2008 for Maruni. Photograph by Mr Yoneo Kawabe, courtesy of Naoto Fukasawa

“My products are already in your mind,” says Mr Naoto Fukasawa. “You just haven’t seen them yet.” Probably best known for his products for Japanese no-brand brand Muji, Mr Fukasawa’s designs are, like Mr Morrison’s, characterised by a love of the simple, of the ordinary, yet so refined that they become compellingly beautiful. He has designed a lift for Hitachi, seating for Narita airport in Tokyo and the extraordinarily elegant Cha kettle/teapot for Alessi. If you had to pick one product, it might be his Hiroshima armchair. Designed for Maruni in 2008, it is almost a memory of an ideal chair, smooth, fluid, familiar and comfortable, its materials smooth and natural. Almost perfect.

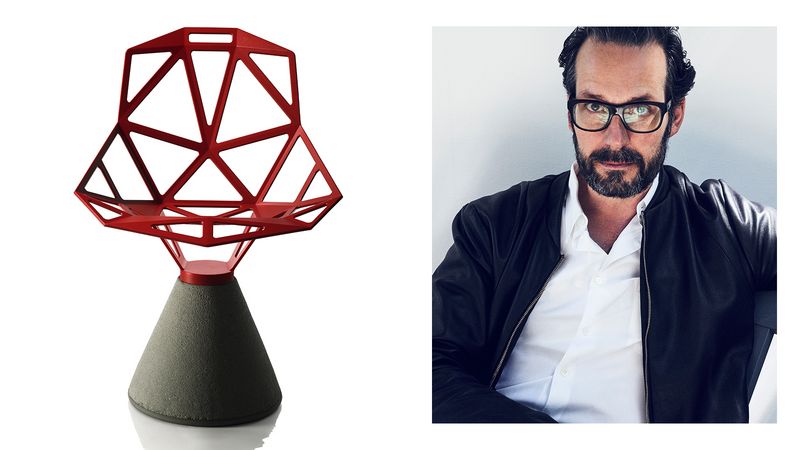

Mr Konstantin Grcic

Left: Chair\_ONE with concrete base, 2004 for Magis. Photograph courtesy of Konstantin Grcic. Right: Mr Konstantin Grcic, in his Munich studio, 2016. Photograph by Mr Markus Jans, courtesy of Konstantin Grcic

German designer Mr Konstantin Grcic does not have a singular style. Instead, he looks at each project anew and the outcomes are unpredictable, occasionally eccentric and usually radically original. At first glance, it looks like his designs eschew the modernist language of functionalism for a more expressive style, but as soon as you analyse the products, you see that every decision emerges from a functional or manufacturing rationale. The angular, spiky form of the popular Miura stool, for instance, looks like some awkward, gangly bird – until you sit on it (very comfortable), lift it (very light) or stack it (they slot into each other perfectly and with great economy). Nothing, perhaps, expresses his particular brand of modernism as well as the Chair One, which has a concrete base. If you think garden furniture is all rattan or white plastic chairs, take a look at this. An angular grid of metal atop a solid cone of concrete, this is a chair that will not blow away and will last, quite possibly, for ever.

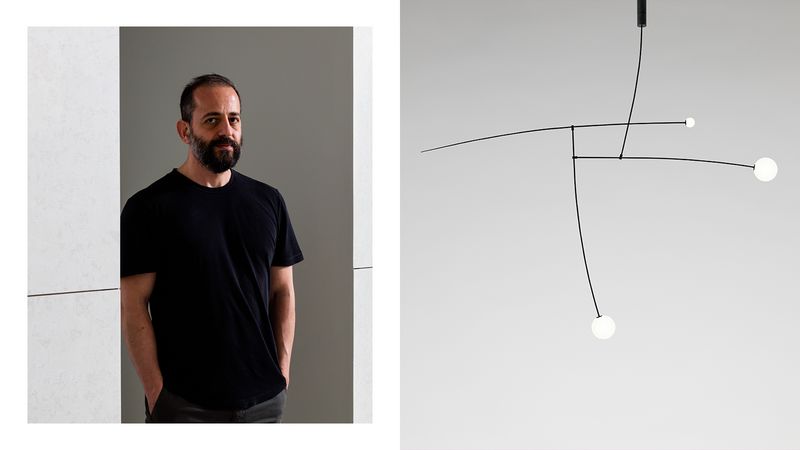

Mr Michael Anastassiades

Left: Mr Michael Anastassiades in Milan, 2016. Photograph by Mr Ben Anders, courtesy of Michael Anastassiades. Right: Mobile Chandelier 14, 2019. Photograph courtesy of Michael Anastassiades

You will already know Mr Michael Anastassiades’ lighting designs, even if you do not recognise the name. It isn’t an exaggeration to suggest that the Cyprus-born, London-based designer has turned lighting into a kind of enigmatic installation art. There are globes balancing on impossible cables or rods, rings of light, webs of bulbs and brass fittings, which have reinvented the lamp as a thing of extraordinary beauty. It’s difficult to pick a single emblematic product, but you could do worse than take a look at Mr Anastassiades’ mobile chandelier series, which reinvents what is surely the most decadent and elaborate light fitting as minimal modernist sculpture. The careful balance and asymmetry bring them as much into the world of art as design, as much Mr Alexander Calder as Mr Thomas Edison.

Studio Swine

Left: Hair Highway Vase, 2014 for Pearl Lam Galleries. Photograph courtesy of Studio Swine. Right: Ms Azusa Murakami and Mr Alexander Groves photographed in their London studio, 2019. Photograph by Mr Bruno Staub, courtesy of Studio Swine

Studio Swine (the Swine stands for Super Wide Interdisciplinary New Explorers) consists of British artist Mr Alexander Groves and Japanese architect Ms Azusa Murakami. Their Royal College of Art project of a chair made out of plastic waste from a beach is not a particularly beautiful thing, but it exudes a powerful symbolism and garnered them global attention. Other items, such as their resin containers in which human hair is incorporated into the material, are utterly exquisite, if eccentric. Everything they do comes from and with a powerful story and they are able to communicate complex histories, narratives and ideas about contemporary consumption and culture purely through design.

Barber & Osgerby

Left: Messrs Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby photographed in their London studio, 2017. Photograph by Mr Dan Wilton, courtesy of Barber & Osgerby. Right: Tip Ton chair, 2018 for Vitra. Photograph courtesy of Barber & Osgerby

Mr Edward Barber and Mr Jay Osgerby came to prominence with their torch for the London Olympics in 2012. Folded from a piece of perforated metal with holes inspired by the Olympic rings, it was a smart and elegant object that spoke of a nation, at last, at ease with modernity (whatever happened to that?). Their work is quiet and clever, ranging from the Tip Ton chair for Vitra, which has a subtle rocking mechanism that allows the sitter to relieve stress on the legs and back, to the elegant profile of the Tab table lamp for Flos. They are also able to work at any scale, from a hotel interior or a shopfront to a spoon or a shower knob. Their Ecco mirror embodies their particular brand of carefully crafted modernism, combining a retro-looking coiled cable with practical rubber rails and an exquisite, hand-blown Murano glass lamp. The complete package: functional, elegant and witty.