THE JOURNAL

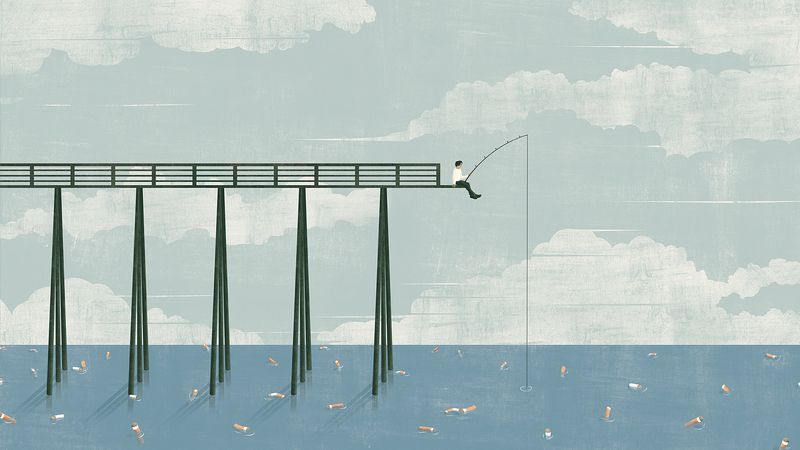

How disposable packaging, bags and bottles are killing the planet, and what you can do to stop it.

It’s incredibly difficult to live in the 21st century and not contribute to the plastic problem. About 8,000,000 tonnes of the stuff pour into the oceans each year, an unearthly stream of polyethylene shopping bags, takeaway cups, plastic drinks bottles and disposable cutlery. It washes up on shores, snags on coral reefs and pools in vast floating islands that stretch for miles out at sea. And by 2025, it’s estimated that there will be enough of it to cover five per cent of the world’s surface in cling film each year. Every day, we’re literally sealing the planet’s fate.

Plastic, of course, is yesterday’s hero. Lightweight, tough, transparent and waterproof, it has built the modern world, allowed fresh food to travel around the globe, given us plastic syringes to save countless lives and made fashion affordable by way of synthetic fabrics. We can use it to stop bullets, mimic haemoglobin in the blood and 3D-print body parts. In the past few years, though, the reputation of single-use plastics has turned to trash, reduced from miracle material to environmental bogeyman. After all, it takes several lifetimes to break down in normal conditions. Call it Blue Planet politics, but the sight of an albatross trying to feed her chicks with plastic on the BBC has precipitated a change in most people’s attitude to polymer waste.

Some 90 countries have introduced complete or specific plastic bag bans and levies, or are in the process of doing so. In India, the state of Karnataka completely banned the use of plastic in 2016. In the UK, the government’s new environment plan, unveiled by Ms Theresa May last month, set out to eliminate all avoidable plastic waste by 2042, but campaigners have called for immediate action. The EU, meanwhile, looks set to plug part of the budget hole left by Brexit with a tax on single-use plastics across 27 member states.

The tide, then, is turning, but 78 million tonnes of plastic packaging produced yearly won’t disappear overnight. What can you, as a consumer, do to lead your own charge against the scourge? Here are six ways to redress the balance.

01. Reuse, not refuse

Turning down single-use plastics is only a first step. We all need to own our own reusables. Mr Michael Gove, environment secretary for the UK, has been setting an example by handing out reusable cups to ministers – Ecoffee Cups are made out of sustainable bamboo fibre – while entertaining the idea of a 25p “latte levy” on beverages sold in disposable cups. Ms Sarah Booth, a sustainability blogger who has previously lived plastic free for a month, takes a reusable coffee cup, steel water bottle and cutlery set with her everywhere. “The fact they’re reusable saves energy and prevents plastic pollution and I love having quirky, brightly coloured items that make baristas laugh and brighten my day,” she says. If you bring a reusable cup, you can save as much as 50p on coffee in Pret A Manger and Starbucks.

02. Rethink food

The real battleground is the supermarket. In Europe, “precyling” no-waste markets are ahead of the curve, eliminating rubbish before it’s created. In Berlin, the sleek, space-age Original Unverpackt is committed to zero waste. Designed by the Los Angeles-based architect Mr Michael J Brown, it has gravity bins containing grains, nuts and legumes. Customers decant measures into their own mesh totes and hessian sacks. In Spain, Ms Judit Vidal and Mr Iván Álvaro’s 12 Granel stores have a similar feel of plastic puritanism. Free of packaging in clear bins, the goods advertise themselves and customers weigh their own produce. The UK has lagged behind, although the plastic-free pop-up Bulk Market in east London proved so popular last year that it’s moving to bigger, permanent premises this month.

When you’re next in the supermarket, check the recyclability of the packaging and avoid products that are packaged with composite materials, such as quiche, pie or sandwich boxes with plastic windows. As an alternative, shop locally. Loose fruit and vegetables at your greengrocer are much cheaper than at the supermarket, where packaged produce is sometimes half the price of loose items. If you have the time and space, growing your own salads and herbs in the garden or a window box is a sustainable option. Milk cartons are a silent scourge, with almost 80 per cent of milk sold by retailers in plastic containers. So order from the local farmer, if it’s practical, or start a campaign to bring back your milkman.

03. Change your habits

Plastic is not the enemy per se. It’s just a material with both an extraordinary lifespan and ubiquity. It may surprise you quite how widespread it is. Many teabags, for instance, are not entirely biodegradable, because they contain a polypropylene “skeleton” that breaks into tiny pieces when the paper breaks down in the compost or soil. Choose loose tea instead. Thermoplastic paints, used on houses, create a plastic dust that has been found on ocean surfaces, so look for brands that use linseed oil or latex as binders. If you don’t know what to do with the plastics you already have, get rid of them responsibly, at a plastics processing yard such as Powerday. (It has outposts in Willesden, Brixton and Enfield.)

In the bathroom, use soap bars instead of liquid handwash and look online for loo roll that is unpackaged or that has compostable packaging, such as Ecoleaf. Baby wipes, hand wipes and facial wipes are typically made from polyester, polyethylene and polypropylene, or a mixture of these plastics and natural fibres. A traditional all-cotton flannel is the eco-friendly wipe alternative. The plastic doesn’t break down, and worse still, it contributes to the “fatbergs” in sewer systems, giant masses of grease and fat stitched together by wet wipes, condoms, tampons and other sanitary items. Last year, the largest fatberg on record in London was found under the streets of Whitechapel. It was so big that it was the weight of 11 double-decker buses and the length of two football pitches. The more waste we produce, the more frightening the monsters we create.

04. Reinvent your wheels

Driving doesn’t just create carbon emissions. Tyres are made from rubber and about 60 per cent plastic (styrene butadiene). The friction, pressure and heat of driving wear tyres down so much they produce an estimated average of 63,000 tonnes per year of plastic dust in the UK alone, as researchers from Keele University point out. If blown into the atmosphere, that dust can contribute to the poor air quality identified by the World Health Organization as a cause of premature deaths. If it is washed into drains, rivers and oceans, it is likely to be eaten by filter feeders such as mussels, which then enter the human food chain.

The industry could move back to natural latex, derived from rubber trees, but this too would have environmental costs. A study by the University of East Anglia says expanding rubber plantations are already “catastrophic” for endangered species in Southeast Asia. If you’re serious about reducing plastic pollution, use public transport.

05. Stop smoking

Was your New Year’s resolution to quit smoking? Stick at it, and not just for your lungs’ sake. Cigarette butts are more of an environmental menace than you might imagine. The filters are made from cellulose acetate, a non-biodegradable plastic, and not paper, as many of us assume. According to the Marine Conservation Society, several trillion cigarette ends enter the environment every year, where they’re mistaken for food and eaten by marine animals. They’ve been found in the guts of whales, dolphins, seabirds and turtles, where they can cause inflammation of the animal’s digestive system and occasionally, if they cause a blockage of the gut, even death. Not only do they shed microfibres, but, once used, they give off high levels of toxins, including nicotine, cadmium, lead and arsenic, making them a potent ocean pollutant.

06. Update your wardrobe

Start with what you’re wearing. Synthetic textiles can shed up to 700,000 microfibres with each wash. Microfibres, as you might expect, are tiny, so have no problem escaping the confines of sewage treatment plants. Once in the water, they’re often ingested by wildlife and can travel up the food chain until they end up being consumed by us.

Fortunately, there are both alternatives and solutions. Brands such as Stella McCartney and Nike have pledged support for the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s rethink on the textile economy, while adidas has collaborated with Parley For The Oceans to turn recycled plastic and netting recovered from the sea into sneakers and swimsuits. Most recently, the two companies partnered to remaster the 1990s EQT Support ADV trainer. The synthetic materials were replaced by recycled fibres, made from waste plastic. Biosteel, a German startup, creates artificial silk fibres and has also teamed up with adidas to produce a biodegradable sneaker.

Some innovations are fruitier than others. AgraLoop, a Los Angeles startup, uses waste from bananas, pineapples and sugar cane to create cellulose-based fibres for textile manufacture.

If you’re not able to commit to a whole new wardrobe, find a washing machine with the right filter. Alternatively, there are ingenious stop-gap measures. The Cora Ball, which came into being following a Kickstarter campaign, can be tossed into the washing machine with clothes where it attracts and collects fibres. The Guppyfriend, meanwhile, is a mesh bag that you wash your synthetic clothes in. It reduces fibre breakage and traps any fibres that do come away.

Eco options

Illustrations by Ms Ana Yael