THE JOURNAL

The rooftop of Public New York. Photograph by Mr Joe Schildhorn/BFA/REX/Shutterstock. Below: Mr Ian Schrager. Photograph by Mr Chad Batka

How New York’s Public is reinventing the boutique hotel.

You know Mr Ian Schrager. He made disco rock at Studio 54 and went on to invent the design hotel that has been ripped off by virtually every hotelier from Birmingham to Beirut. Without Mr Schrager, there would be no lobby scene, no go-to bars, no signature scents, no hot staff and buzzing nightclubs, no baffling taps in the bathrooms. Hotels would still be full of swags and ruffles.

At 71, with millions in the bank, a young son and, thanks to one of the last acts of President Barack Obama, a pardon for his 1980 tax evasion conviction at Studio 54, you might think he would hang up his mood boards. Not a bit of it. The master tastemaker is at it again, wanting to reinvent hotels for the Airbnb generation.

“This is the most important idea of my career, and it will be as impactful as the boutique hotel,” he says in his trademark Queens rasp. “It will be a game changer.” The “this” he’s talking about is Public, his latest hotel, where we meet on one of those New York summer mornings that are so hot your brain feels like a hot dog.

The property, on New York’s Lower East Side, turns everything Mr Schrager has done before on its head. If you’ve ever been turned away from a nightclub or made to feel substandard or poor, Mr Schrager is the guy to blame. He practically invented the velvet rope at Studio 54. If you didn’t look right, you were turned away. He took his exclusive attitude with him when he opened Morgans, the Royalton, the Paramount, the Hudson and the Gramercy Park Hotel in New York. It was still there when he launched the Delano in Miami, the Clift in San Francisco and the Mondrian in Los Angeles. He even brought it to London at his St Martins Lane and Sanderson hotels, the hotspots of the early 2000s.

If you were one of the lucky few who did manage to get into one of these establishments, you had to be prepared to cane your credit card. Mr Schrager was the master of high prices. “Whenever those hotels got successful, whenever the alchemy set in, I started raising prices,” he grins. “I admit it.”

Now, though, you can cast off your razzle-dazzle finery. Put away your carefully practised too-cool-for-school look. Dump the Amex black card. Mr Schrager has changed. He’s gone, erm, budget. “Public is a value proposition that offers affordable luxury for all,” he says. “I’m going into the motel market, but bringing style, sophistication, refinement, entertainment and great service.”

King Great View Room at Public New York. Photograph courtesy of Public New York

Motel? He’s not kidding. When you check in to Public New York, what is not present is as glaring as what is. No bellboys, no valets, no doormen, no check-in desk, no spa, few amenities in the room, no minibar, no bathrobes, no room service, no turndown. Why? “Because they’re all bullshit,” says Mr Schrager. “People don’t care about that stuff anymore.”

Luxury has changed, he argues. “It’s simpler, more pared down, less pretentious and more accessible,” he says. “Look at Apple. It offers luxurious products and services but at prices most people can afford.” Small wonder that the service at Public is as streamlined as an iPhone. The staff, called “public advisors”, are trained to handle any kind of query rather than passing callers on to a puffed-up concierge or restaurant manager, which is time consuming and annoying. “It’s less grand, less obsequious,” says Mr Schrager.

“You can’t stop a good idea that offers something new and distinctive. The only way to fight a good idea is with another good idea”

The hotelier’s hotelier is performing a cultural U-turn for another, much bigger, reason. The industry that he has transformed is under threat as never before. “Airbnb is a complete disruption,” he says. “I rank it right up there with blacksmiths when the car came. They are coming after our children.”

The numbers confirm the threat. “The worst idea that ever worked,” as Airbnb’s founders Messrs Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia refer to their 2008 home-sharing startup, has become the most popular and innovative global startup in tech history. In only eight years, it has grown from a single flat in which Messrs Chesky and Gebbia rented out an airbed and offered breakfast cereal to guests to help pay the bills, to three million properties for rent in 34,000 cities in almost 200 countries. Every second, three people check in to an Airbnb property.

What to pack

With an average nightly spend of £80 (Airbnb takes a cut of about 12 per cent), Piper Jaffray, an investment bank, estimates bookings reached £12bn last year, an almost unimaginable 285-fold increase on the £42m the firm took in 2010. On a peak night, more than 1.8 million people are Airbnb-ing around the world. “That’s the equivalent of a mid-size city,” Mr Chesky likes to say. Overall, more than 100 million guests have stayed in an Airbnb. That makes it the world’s biggest hospitality firm, worth £25bn. That’s more than Marriott, Hilton, InterContinental or Hyatt, the world’s largest hotel outfits.

After being slow to wake up to the threat Silicon Valley posed, just like the music industry when it was confronted by MP3 file-sharing sites, notably Napster, hoteliers are making the same mistakes as they try to fight back. The big hotel groups are trying to use the courts and city authorities to clip Airbnb’s wings. They’ve had some success. New York and Barcelona, in particular, have begun fining hosts who rent out their homes on Airbnb in breach of local housing laws or lease agreements, which has reduced the number of Airbnb listings in each city.

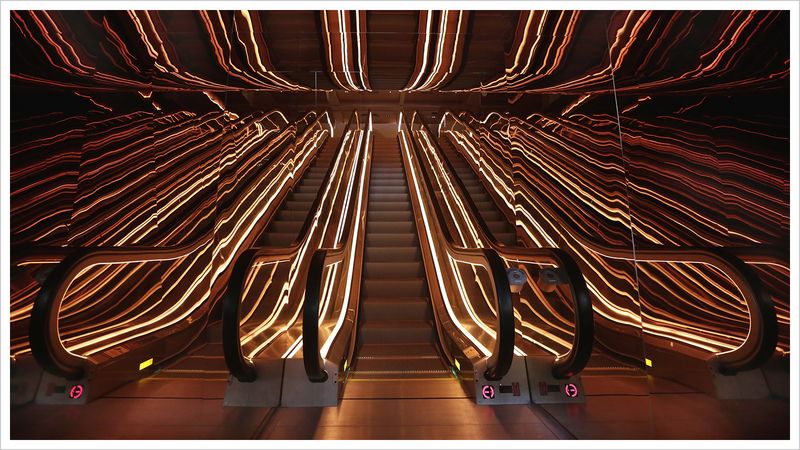

Public’s escalators. Photograph by AP/REX/Shutterstock

But, Mr Schrager warns, trying to use legislation to kill a popular idea never works. “You can’t stop a good idea that offers something new and distinctive,” he says. “The only way to fight a good idea is with another good idea.” He believes his 370-room hotel on the site of a former car park is that very idea.

Public uses three weapons to take on Airbnb. First, it beats it on hardware, Mr Schrager argues. Messrs Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, the Swiss pair behind Tate Modern in London, have spent four years creating the 29-storey tower. Mr Ascan Mergenthaler, the firm’s senior partner, tells me the building “is a new icon that breaks new ground with texture, rhythm, finishes and functionality”. He singles out the “concrete skeleton with windows that push through like jewels at a slight angle, which means they reflect the sky and it’s hard for people outside to look in”.

What to pack

Mr Schrager points to the furnishings. The Mr John Pawson-designed furniture in the front garden and the entrance with hallucinogenic lighting create “an instantly exciting arrival”. Once inside, the interior that offsets the rough-hewn – bare wood and concrete – with vibrant coloured soft furnishings, is new and challenging. “Airbnb can’t offer that kind of intelligent, innovative architecture and design for the price that we are charging,” says Mr Schrager.

And he wants to match Airbnb on price. The rooms are small – 10ft x 20ft – but as perfectly formed as they come. They feel like cabins on a luxury yacht with an Italian white oak bed pod that looks straight out across the city. They come with a trademark Mr Schrager dramatic trick. Open the door and the curtain automatically rises to reveal the million-dollar view. There’s a bench sofa, a desk and a shower. Their size, coupled with the savings made on doing away with the traditional white-gloves-and-epaulets service, means rates start at just £120 a night – crazy cheap by Manhattan standards.

The Public lobby. Photograph by AP/REX/Shutterstock

Mr Schrager’s third stick to beat Airbnb is service. He wants to offer the best coffee bar, restaurant, work space, bar, nightclub and gym, so you never have to leave the hotel. Downstairs is Louis, named after his seven-year-old son, where you can buy coffee and whatever groceries you need and take them to your room and put them in the large fridge.

There are meeting rooms and refectory tables for working. Here, Mr Schrager is, ironically, borrowing from the sharing economy in which Airbnb is a pioneer. “It’s our answer to WeWork,” he tells me as we walk through the lobby and he grabs his 500th coffee of the morning. It’s also his response to the one hotel group for which he confesses a little jealousy – Ace. While he successfully leveraged his success at Studio 54 to bring the night into his hotels with the lobby scene, hot bars and cool nightclubs, Ace is the first to bring the day scene into hotels. Walk into any Ace from 9.00am to 6.00pm and it looks like a hackathon. Hipsters are working on this or that startup, coding, networking. “That’s smart. That’s modern,” says Mr Schrager.

What to pack

But Mr Razzle Dazzle still owns the night. The rooftop bar at Public has the best 360-degree views in Manhattan because the hotel is the tallest building in the neighbourhood and halfway between the skyscrapers of Downtown and the Empire State Building. Every night, bands play, dancers perform and comedians appear in the downstairs nightclub-cum-theatre, called Public Arts.

Put style, service, entertainment and price together, and hotels are back in the game, argues Mr Schrager. “It’s revolutionary and it’s the future,” he says. Your move, Airbnb.