THE JOURNAL

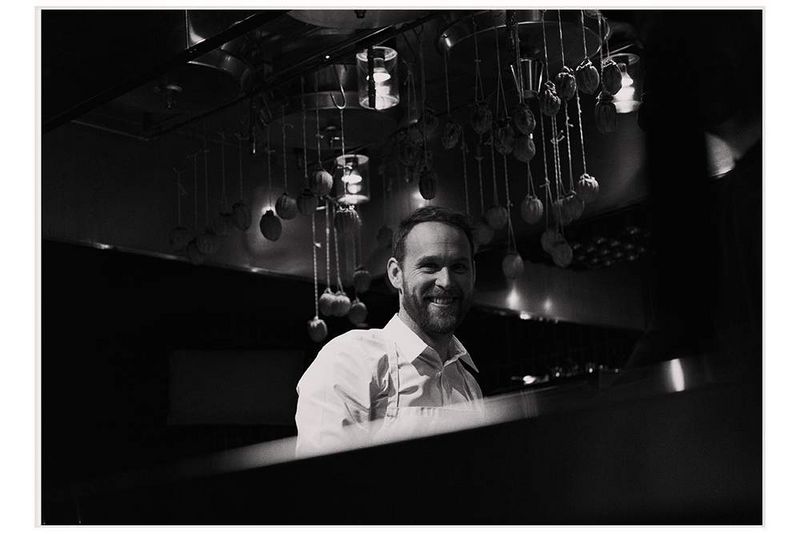

The footballer-turned-chef on breaking with tradition – and why all he really wants is a good night’s sleep

Like many professional chefs, Mr Björn Frantzén can trace his obsession with food back to a single, eye-opening moment. His epiphany came at the age of 12, he says, with a “perfect” steak-frites: “grilled beef, crunchy French fries, sauce béarnaise and a tomato and red onion salad with a perfectly balanced balsamic dressing. I knew straight away that I needed to become a chef, if only so I could learn to cook and eat this every day.”

Such single-mindedness is hardly unusual in chefs, especially those with the drive to make it all the way to the top. As the owner and head chef of Restaurant Frantzén, the first and so far only restaurant in Sweden to hold the Michelin Guide’s fabled three-star rating, he certainly falls into this category. What’s unique about Mr Frantzén is that despite this precociousness, this clarity of ambition, his culinary career was far from certain. In fact, if it hadn’t been for an unusual heart condition, he might not have become a chef at all.

Restaurant Frantzén is the first and only restaurant in Sweden to hold three Michelin stars

Until his late teens, Mr Franztén was living a double life. On the one hand, he was an aspiring chef studying at a local culinary college; on the other, he was a promising footballer signed to Stockholm’s biggest club, AIK. As he rose through the youth ranks, football overtook cooking as his primary ambition. Standing in the way of a professional career, though, was a congenital heart condition that could cause his pulse to race to more than 200 beats per minute.

“The club told me that if I wanted a senior contract, I had to get it fixed. But during surgery, the doctors found a problem. They told me that there was a small chance – a one-in-a-hundred chance – that I’d need a pacemaker.” What might have seemed like a negligible risk to anyone else was enough for Mr Frantzén to call time on his footballing career.

His heart condition was perhaps a blessing in disguise. A born perfectionist – “If you’re going to do something, do it properly or don’t do it at all,” he says – there was never a possibility that he could have continued with both football and cooking. His gruelling training regimen at AIK meant that he was already struggling to keep up with his contemporaries at catering college: “When I was 19, I could hardly tell the difference between coriander and parsley,” he says. “I was falling so far behind. So, I said, that’s it. I’m done with football. I quit. Let’s forge ahead with the plan B.”

Mr Frantzén knew he wanted to become a chef at the age of 12, after having “perfect” steak-frites

By cutting his losses and moving on, he was able to throw himself wholeheartedly into cooking. And whatever hole football left in his life was soon filled by the rush of working in a professional kitchen. “The atmosphere 10 minutes before opening in a Michelin-starred restaurant is the closest you’ll ever get to that feeling of being 10 minutes away from kick-off in the changing rooms,” he says. “I was hooked straight away.”

The calculated, risk-averse nature that saw him nip a promising footballing career in the bud has stuck with Mr Frantzén throughout his life. When he launched the first Frantzén in 2008 with his then partner, Mr Daniel Lindeberg, it was financed not by an independent investor, as tends to be the case in the notoriously risky restaurant business, but with a bank loan. Convincing the bank to lend them the money was, he says, no easy task.

“The atmosphere 10 minutes before opening in a Michelin-starred restaurant is the closest you’ll ever get to that feeling of being 10 minutes away from kick-off in the changing rooms”

The food is rooted in the principles of French cuisine, but with a light touch inspired by Asian food

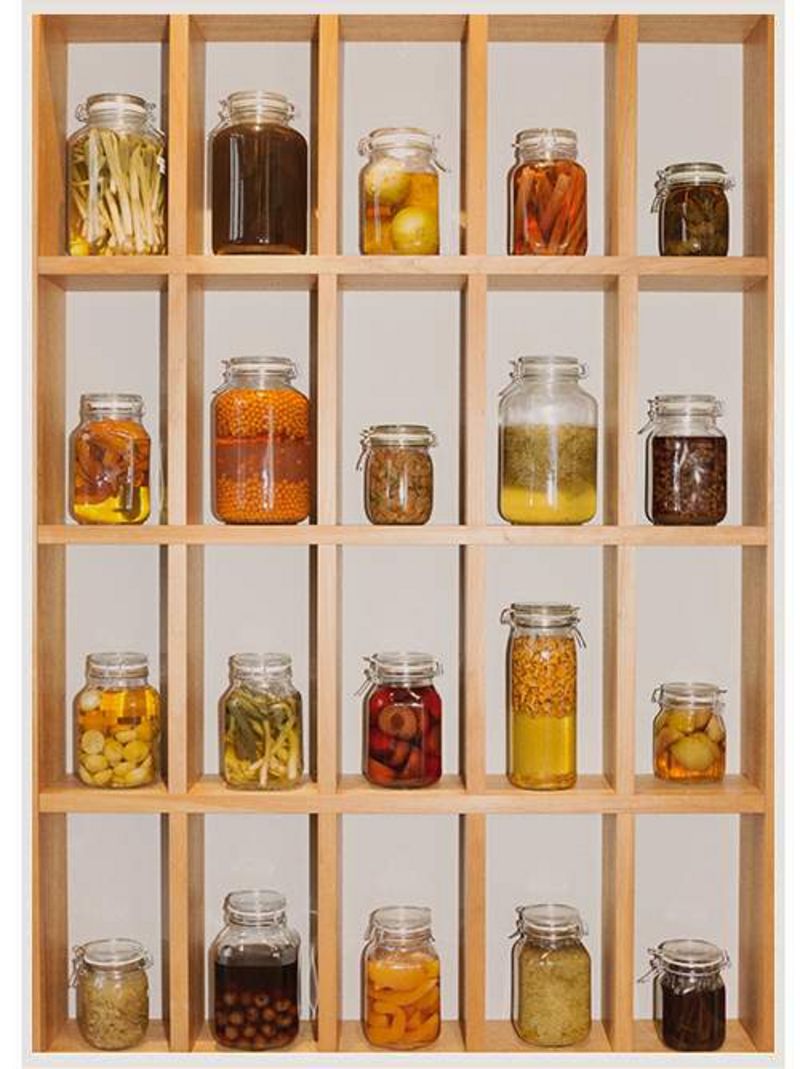

There’s a strong local Swedish flavour with the generous use of pickled and fermented vegetables

“It was very rare, almost unheard of, to get a bank loan for a restaurant back then,” he says. “It’s a low-margin business, especially in a country like Sweden, where you get taxed on almost everything. Preparing a menu is one thing. But if you want to survive, you need to know your finances like the back of your hand.” The exhaustive 40-page business concept presented to the bank was enough to convince them that Mr Frantzén was, at least by the standards of the restaurant industry, a safe pair of hands. Their faith has since been rewarded: the chef now presides over a global business empire comprising six restaurants, with another four scheduled to open in 2020 alone.

It’s an empire built on a particular vision of modern fine dining. “The way we think about luxury is changing,” explains the chef, whose tattooed forearms mark him out as a card-carrying member of the culinary new school. “It’s not about gold and marble anymore. Our guests come here in Valentino sneakers and SAINT LAURENT ripped tees, they drink grand cru wines and they have a good time.” Indeed, it can feel as if his restaurant is making a point of flaunting the rules. As guests ascend from the ground-floor reception to the top-floor lounge, they’re treated to the opening riff of “Enter Sandman” by Metallica. You don’t get that kind of elevator music at l’Arpège.

Mr Frantzén opened his restaurant in 2008, after ending his football career to attend culinary school

“The way we think about luxury is changing. It’s not about gold and marble anymore”

As for the food, it’s rooted in the principles of French cuisine, but with a lightness of touch more typically associated with Asian food. “This is a bit like swearing in church,” he says, leaning forward in his chair, “but if you ask me, the French destroyed a little bit of the beauty of the tasting menu.” While it might be a stretch to cry blasphemy, this kind of statement is sure to ruffle a few establishment feathers. After all, it’s generally accepted that no country has done more for the advancement of the culinary arts than France; the modern tasting menu, or menu dégustation, is said to have originated in 1960s Paris with the nouvelle cuisine of chefs such as Mr Paul Bocuse, whose influence still weighs on fine dining today.

What’s less commonly understood, however, is that these chefs were themselves influenced by regular trips to Japan, where they learned about the kaiseki – a traditional multi-course meal with its roots in Buddhist tea ceremonies. On returning to France, they married the concept of kaiseki – simple, elegantly plated dishes served in theatrical procession – with the methods and ingredients of French haute cuisine, in doing so setting the blueprint for the next 50 years of fine dining. But it’s a marriage that was not without a certain friction, says Mr Franztén. “French cookery is high in lactose, gluten and fat. If you’ve ever eaten at one of these legendary French restaurants, you know the feeling. You get halfway through the menu and you’re already stuffed.”

Frantzén now comprises six restaurants, with another four set to open this year

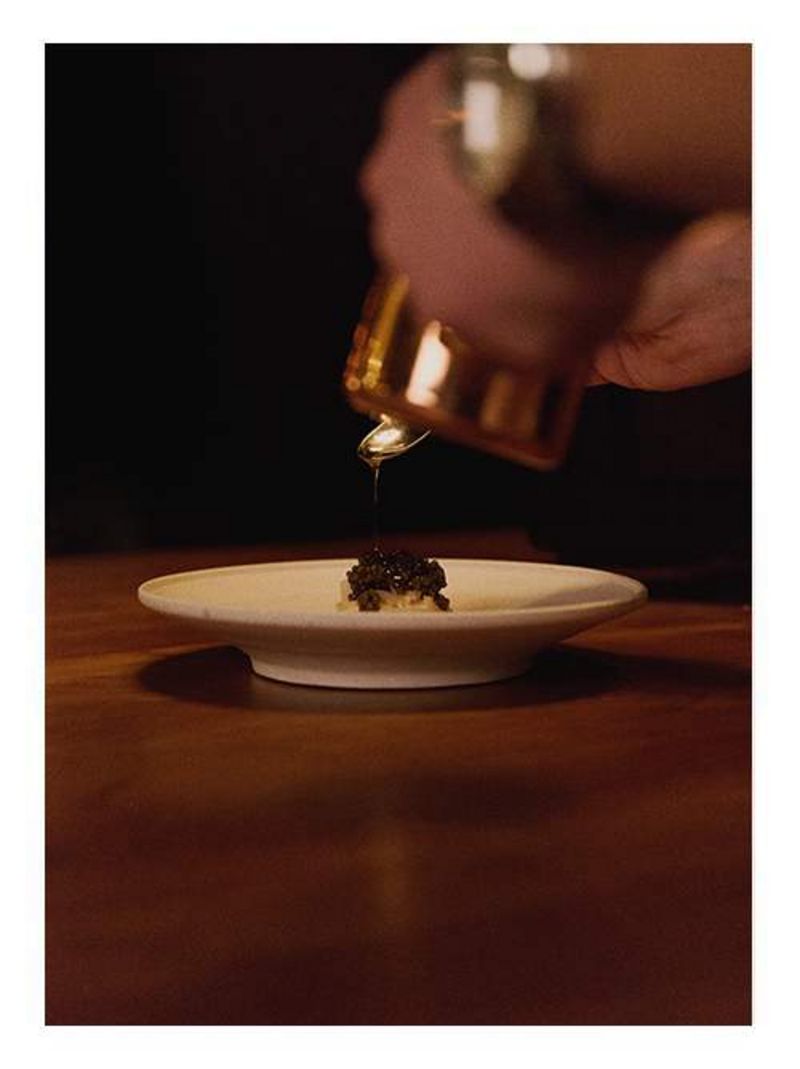

He has not, to be clear, abandoned French cuisine altogether. Indeed, one of his signature dishes is “fattiga riddare”, an opulent take on French toast. But while a typical menu at Frantzén might include foie gras, langoustine, shaved black Périgord truffle and caviar, you’re just as likely to encounter sea urchin, chawanmushi, miso and dashi. There’s a strong local flavour, too, with the generous use of pickled and fermented vegetables underlining Frantzén’s identity as Swedish above all else.

It all must seem a very long way from that formative plate of steak-frites eaten more than three decades ago. For Mr Frantzén, though, it’s clear that not much has changed. “For me, life isn’t more complicated than finding out what makes you sleep well at night. That’s all there is to it.”