THE JOURNAL

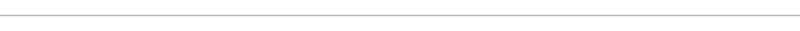

Mr Aristotle Onassis, 1966 Bettmann/ Corbis

“The secret of business is to know something that nobody else knows,” said the Greek tycoon Mr Aristotle Onassis. The same could be said for dressing well. Entrepreneurs, financiers and other masters of the universe often succeed in their vocations because they possess an uncanny ability to shift from the big, macro-economic picture to the micro, tiniest details. Likewise, the secret to business dressing is being able to keep the overall effect of an outfit in mind even as you’re selecting what sort of cufflinks to wear. Ever wondered why middle managers are often middling dressers? So, in our never-ending efforts to help you dress for the job you deserve, let us offer some aspirational examples of those boardroom blades who left “the suits” standing.

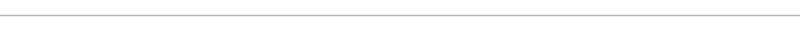

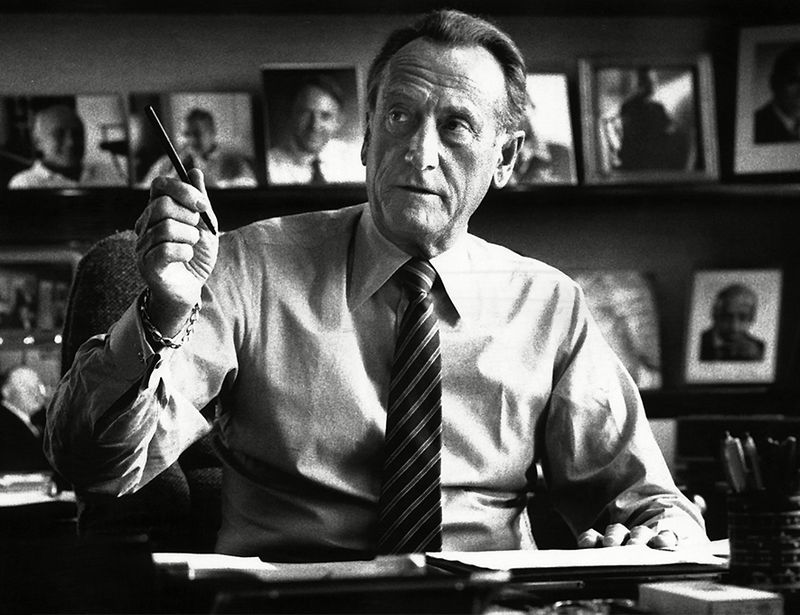

Mr Fred Hughes

Mr Hughes, 1983 Richard Young

If Mr Andy Warhol more than fulfilled his oft-stated aim of becoming a “business artist”, it was Mr Fred Hughes, his manager and executor, who took care of the former. A Texan aesthete who learnt the art trade from local patrons and collectors the de Menils, Mr Hughes met Mr Warhol at a Velvet Underground gig in 1967: “Fred was conspicuous – one of the only young people around who insisted on Savile Row suits,” wrote Mr Warhol in his book POPism. Mr Hughes accessorised his bespoke Anderson & Sheppard ensembles with shoes from John Lobb and Penhaligon’s Blenheim Bouquet cologne, while the rest of the Factory habitués favoured leather and denim. “Fred got more and more outrageously elegant,” wrote Mr Warhol, “in black braided jackets and shirts with bow ties to match.” Mr Hughes kept photographs of the Duke of Windsor, King Umberto of Italy and Mr Fred Astaire in his home, and took regally louche inspiration from all three. Anyone looking to mix uptown savoir-faire with downtown brio can take equal inspiration from Mr Hughes.

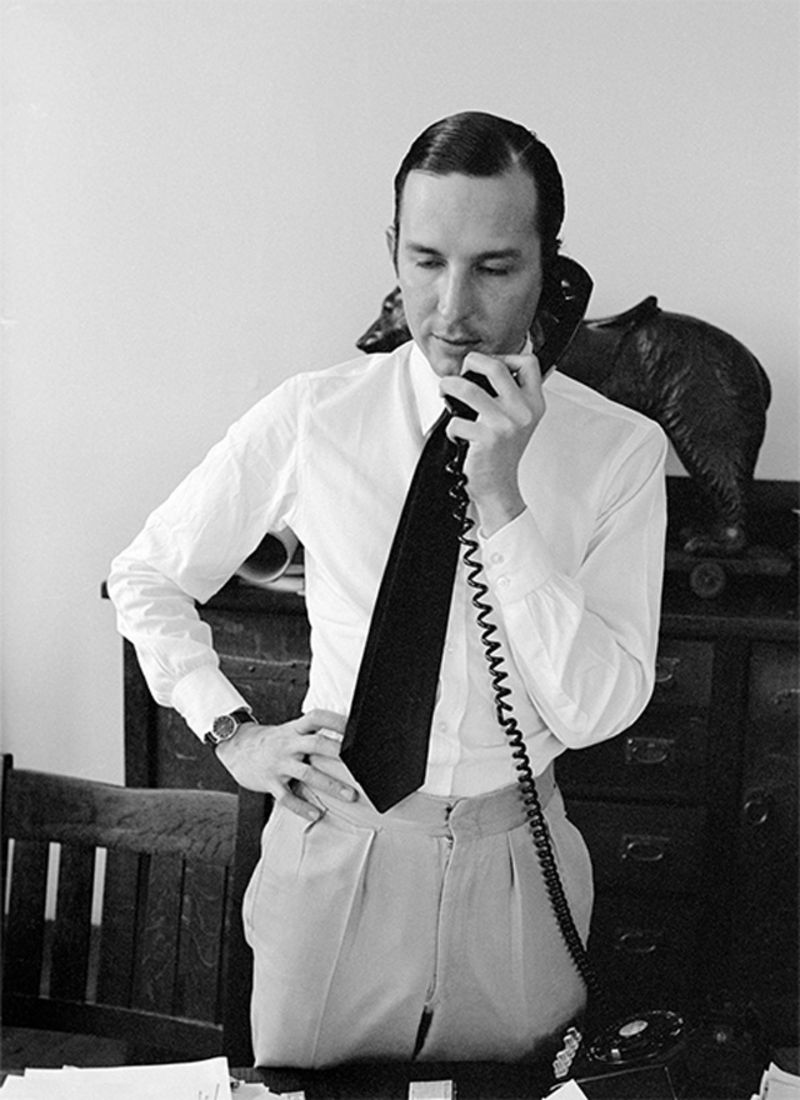

Mr Henry Ford

Mr Ford, 1914 The Ford Motor Company

Inventor, holder of 161 US patents, populariser of the production line, godfather of the motor car as practical conveyance and thus the man who did more than most to shape the course of modern existence. But was he also the nascent poster boy for a certain strain of Americana-heritage craftsmanship in menswear? Mr Henry Ford seems an unlikely inspiration for the retro-futurist stylings of the likes of Engineered Garments and Woolrich, but the devil is in the detail: the high penny collars, the soft shoulders, the rolled lapels, and even the lumberman tan and artfully greased hair would all be at home in a Hackney vape bar (appropriately, as Mr Ford once penned a screed against smoking), or a Bushwick artisanal coffee house (where, like his Model T cars, you could have any coffee “in any colour you want, so long as it’s black”). And if Mr Ford showed an uncommon lightness of touch in his suiting shades, that’s because he anticipated the ethical fabric debate by a century or so, running up three-pieces in a soya bean protein fibre of his own devising that he called “soybean wool”. The trail blazed by Mr Ford shows that soft power can still pack a punch.

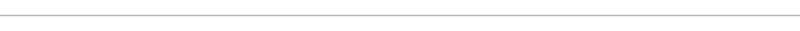

Lord Hanson

Lord Hanson, 1991 Tom Pilston/ Rex Features

One of Mr James Hanson’s assistants once opined that “the word ‘martinet’ could have been coined for him”. He was indeed a stickler for discipline, whether asset-stripping the companies he took over in the 1970s and 1980s (making him the first British businessman to earn more than £1m a year, and winning him faint praise as “Europe’s most potent capitalist” and “the very archetype of the Thatcherite tycoon”), or maintaining punctilious standards of punctuality, politeness and correct dress. The latter was a legacy of his teenage spell in the 7th Battalion, the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. It was facilitated for Mr Hanson in his later years by his tailor, Mr Douglas Hayward, who also dressed Sir Michael Caine and Mr Steve McQueen for The Thomas Crown Affair, and who gave Mr Hanson’s patrician proclivities a contemporary, rakish spin. Mr Hanson’s legacy to modern corporate raiders? It’s the telling details that set you apart from the pack – the slightly longer collar points, the turn-back cuffs and the silver bracelets all allude to the buccaneer within.

Mr William Randolph Hearst

Mr Hearst, 1930 Ullstein Bild/ Topfoto

“I never knew a person throw wealth around in such a dégagé manner as Hearst,” wrote Sir Charlie Chaplin in his autobiography. Indeed, Mr William Randolph Hearst commanded an outlay commensurate with his status as America’s biggest press baron in the first half of the 20th century, inventing “yellow journalism” (aka tabloid hackery) and becoming the inspiration for Mr Orson Welles’ Charles Foster Kane along the way. Monuments to his profligacy included Hearst Castle, his California chateau built from the offcuts of various English castles shipped across the Atlantic in crates, and the wardrobes therein, full of bespoke finery from Henry Poole & Co of Savile Row. Mr Hearst had the dandy’s delight in mixing colour, pattern and texture, as the Poole order books show. He teamed grey vicuna jackets with graphic-print ties of his own design, or blue beaver double-breasted coats with checked tweed jacket-vest-knickerbocker combinations worthy of Mr Kenneth Grahame’s Mr Toad. The lesson – that you don’t need to look boardroom-formal to mean business – is clear, though Hearstian levels of chutzpah help in pulling it off.

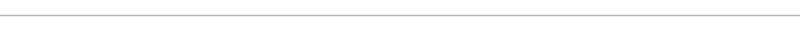

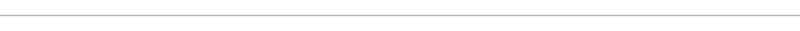

Mr William S Paley

Mr Paley, 1933 Keystone/ Getty Images

Panache was Mr William S Paley’s calling card during his 60-year chairmanship of the Columbia Broadcasting Corporation, christened “the Tiffany network” under his stewardship. His suite at New York’s St Regis Hotel was an immaculate cube designed by Mr Billy Baldwin and filled with French furniture, modernist masterpieces and exquisite objets d’art. The centrepiece of his office was an antique chemin de fer card table rather than a drone’s desk. His wives were the socialite and Algonquin set mainstay Ms Dorothy H Hirshon, and the leading “swan” of Mr Truman Capote, Ms Barbara “Babe” Cushing Mortimer. His peak-lapelled dinner jackets were handmade at Huntsman in Savile Row and maintained by his valet, Mr John Dean, a former equerry to Prince Philip. All told, Mr Paley’s raison d’être was to display, as he put it, “a certain standard of taste”. In a world where The Real Housewives of New Jersey clogs up the networks and executives sport skater shorts, it’s a more vital aim than ever.

Mr Gianni Agnelli

Mr Agnelli, c1970 Authenticated News/ Getty Images

Mr Gianni Agnelli, the industrialist who ran Fiat during its glory years in the 1960s and 1970s, earned himself many soubriquets: “L’avvocato”, in honour of his law degree; “Rake of the Riviera”, in honour of... well, you can guess. But his place in the style pantheon is assured thanks to his mastery of sprezzatura, that form of sartorial insouciance where, in the words of Sir Hardy Amies, “a man should look as if he’s bought his clothes with intelligence, put them on with care, and then forgotten all about them.” Mr Agnelli subverted his handmade Caraceni suits and Battistoni shirts by deploying various “tricks” – including wearing his watch (usually a Fratello) over his shirt cuff; sporting high-top hiking boots with his formalwear; letting the collars of his button-down shirts flap free; and configuring his tie so that the skinny end dangled below the fat end. Many have since attempted to copy one or more of these affectations, but the true would-be heirs to Mr Agnelli’s inimitable style are those who find their own forms of elegant, just-so nonchalance.

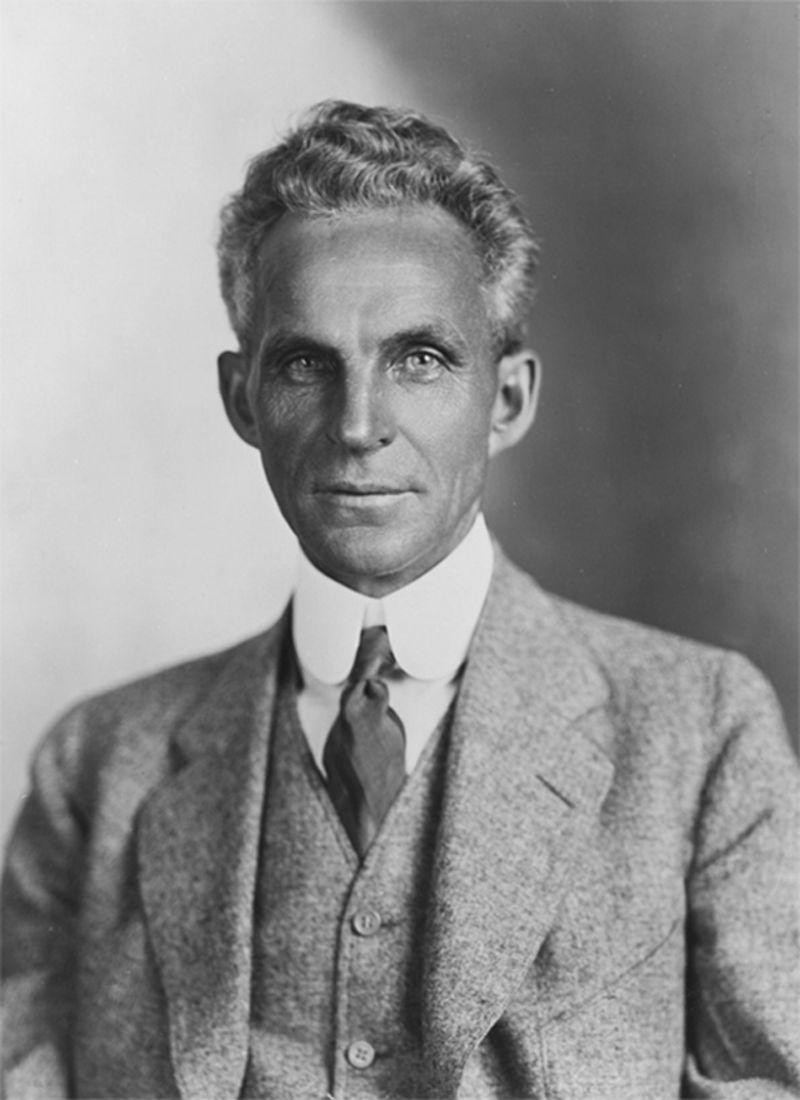

Mr Aristotle Onassis

Bettmann/ Corbis

“Everyone knows three things about me,” the pugnacious Mr Aristotle Onassis once rasped. “I’m f***ing Maria Callas, I’m f***ing Jacqueline Kennedy, and I’m f***ing rich.” So we’ll quickly move on to a less celebrated attribute of the infamous shipping magnate: his innate sense of style. The boardroom-to-speakeasy swagger with which he wore his Caraceni double-breasted suits and waterfalling pocket squares is an object lesson for today’s DB-revivalists. The breezy dash of his off-duty ensembles – spotless white trousers, unbuttoned polo shirts, sockless loafers, chunky statement sunglasses from François Pinton of Paris, unlit cigarette perennially dangling from the corner of his mouth – became the template for the haute Riviera boulevardier. This was only enhanced by the fact that they were usually sported on the deck of the Christina O, his own superyacht, or, indeed, on the corniche of Skorpios, his own private island. “Don’t get too much sleep and don’t tell anybody your troubles,” Mr Onassis once advised; a reminder for today’s uptight hedge-funders or social-media bean-spillers that his approach to life, as to dress, was far from precious – and all the better, and more charismatic, for it.