THE JOURNAL

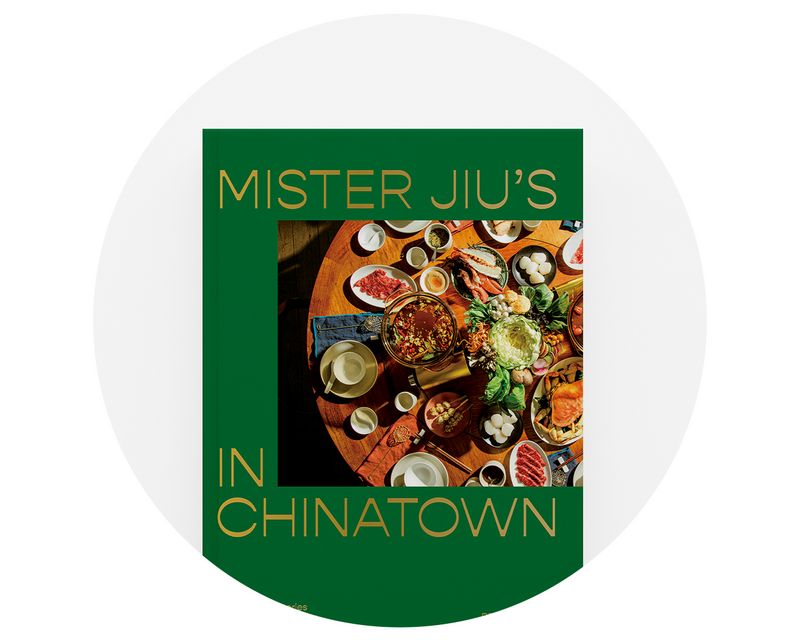

Hot Pot and accompanying dishes set up on a circular table. Photograph by Mr Pete Lee, courtesy of Penguin Random House

_San Francisco-born chef Mr Brandon Jew owns the Michelin-starred Mister Jiu’s in the City’s Chinatown, and Mamahuhu in Richmond. He is also the latest member of MR PORTER Style Council. Below, in his own words, he gives us an introduction to some Lunar New Year traditions, tells us how he’s celebrating this year (and, more importantly, what he’ll be cooking). _

Chinese food and celebration are about getting together with your whole family and friends, so it’s hard at the moment. The food is meant to be shared among everyone. Last year, Chinatown in San Francisco was experiencing the effects of Coronavirus before we had to shut down. Tourism had dropped in January and February, and the parade and the festivities were gone. So, there has been a chance for us to think – how can we still celebrate these traditions with each other? How do we make it feel festive? Even in a smaller group, some of the food we eat can retain the meaning and symbolism of Chinese New Year.

More people use “Lunar New Year” because it’s also celebrated among Southeastern Asian countries – Thailand, Laos, Vietnam. I’m just used to saying “Chinese New Year”. Lunar New Year follows the moons. It begins on a different day each year (this year is 12 February) because it is associated with the second new moon after the winter solstice. It’s a celebration of harvest.

You’re supposed to do a deep clean in the days leading up to Chinese New Year. The superstition is that you’re trying to get rid of all the bad stuff that gets caught in the corners. You’re allowing good luck and fortune to come into your space.

Last year was the Year of the Rat. I think that correlated to 2020 – it was about being scrappy, trying to survive; 2021 is the Year of the Ox. The ox is all about being persistent, head down, working hard, staying true to what you believe in, perseverance. That’ll be a strong symbol. I’m not as superstitious as a lot of my family, but I’m starting to think I should be. I’m trying to practice some of the traditions.

Mr Brandon Jew. Photograph by Mr Pete Lee, courtesy of Penguin Random House

The food that we eat is a celebration of a really full heart. You’re celebrating the fruits of your labour and different dishes hold different symbolism. On the first day of new year, you are supposed to eat only vegetarian food, to signify that nothing has been killed. This is also a day of rest and paying respect to elders. Over the course of Lunar New Year, certain meats are symbols of good fortune, such as meatballs, which represent a happy reunion. Boiled dumplings represent money.

**There is a hanging BBQ dish called char siu pork. **The pork is stained red from the red fermented tofu and symbolises good luck and good fortune. There is also a dish with a super long noodle, which represents longevity and long life. One of the dishes that I know is popular in many Southeast Asian countries is called yusheng. It’s a raw fish dish – sashimi almost. It has a lot of vegetables and some noodles and a simple vinaigrette.

At my parents’ house, we would do hotpot. Hotpot is one of those dishes that, as a host, is easy because everything is prepped in advance, and you get to sit down with everyone. My mum would make a bunch of broth and have vegetables, meat, sauces and dumplings and have it all laid out on the table while it boils. At the very end, we’d drink the soup. For me, the celebration usually involves around 12 people. This year, you can still have a celebratory hotpot that’s made for two to four people. It’s cold at the moment, so it’s ideal. And it’s healthy. Kind of. But if you don’t have the time or means to make a hotpot broth, something like this oxtail soup, taken from the Mister Jiu’s In Chinatown cookbook, will be just as warm and nourishing.

Oxtail soup. Photograph by Mr Pete Lee, courtesy of Penguin Random House

Oxtail soup

Oxtail, a favourite of resourceful immigrants everywhere, is now among the priciest specialty cuts at the butcher’s counter. Even back when it was cheap, my busy mom knew to treat it right. She blanched it in boiling water, then braised it for hours in our slow cooker. When I started cooking professionally, I tried new techniques on oxtail, but the results were never as succulent or as satisfying as hers. I came to my senses and, aside from salting before blanching, I basically do it her way, coaxing out flavour with patience rather than a hard sear. This recipe is a variation of what we do at the restaurant, where we take the meat off the bone, fold in bone marrow, and roll it into a mustard-leaf torchon. But, deep down where it matters, both restaurant and home versions keep my mum’s dish in mind.

Plan ahead: you’ll need 6 hours for salting and simmering, plus time to make a batch of chicken stock. If you can, leave the oxtails in the broth and chill overnight for maximum tenderness and flavour.

Makes 6 servings

Ingredients

2.3kg (5lb) oxtails, cut into 2in-thick pieces

Kosher salt

2 tsp black peppercorns

2 tsp white peppercorns

2 star anise pods

3 bay leaves

2 slices unpeeled ginger (¼in-thick)

4.7l (5qt) cold chicken stock

230g (8oz ) daikon or other radish, peeled and then roll cut

230g (8oz) carrots, peeled and then roll cut

115g (4oz) fresh shiitake mushrooms, stems trimmed, halved if very large

1 tbsp neutral oil

Fresh watercress or Chinese or regular celery leaves dressed in peanut or nut oil for garnish

Special equipment:

Cheesecloth, kitchen twine

Method

Season the oxtails all over with 1 tbsp salt and let sit at room temperature for 2 hours.

In a small frying pan over medium heat, combine the peppercorns and star anise. Toast, tossing or stirring frequently, until fragrant, about 2 minutes. Immediately transfer to a plate and let cool. Make a sachet of the spices and bay leaves by wrapping in a double layer of cheesecloth and tying closed with kitchen twine.

Add the ginger to the same pan over medium-high heat and char until blackened in spots, 3 to 4 minutes per side.

Fill a 10-quart or larger pot halfway with heavily salted water (it should remind you of seawater) and bring to a vigorous boil over high heat. Add the oxtails and blanch for 1 minute, then transfer them to a colander and rinse under cold water. Discard the blanching water and rinse out the pot.

Return the oxtails to the pot. Add the sachet, ginger and chicken stock and bring to a simmer over high heat. Turn the heat to medium-low and very gently simmer, uncovered and skimming every hour or as needed, until the oxtails are tender, but not falling off the bone, about 4 hours.

About an hour before the oxtails are done, taste the broth and season with salt.

Preheat the oven to 220ºC (425ºF). Place the daikon, carrots and mushrooms on a rimmed baking sheet, drizzle with the neutral oil, and toss to combine. Roast until they start to brown on the bottom, about 20 minutes, then remove from the oven and let cool. Transfer to an airtight container and store in the refrigerator for up to 1 day.

Transfer the oxtails to a large bowl. Line a colander with a double layer of cheesecloth and fit over a 5qt pot. Strain the broth and discard the solids. If serving the same day, skim the fat from the surface of the broth. If serving the next day, return the oxtails to the broth. Let cool, then cover and refrigerate.

When ready to finish the soup, skim the hardened fat from the surface of the broth. Warm over medium heat until the broth liquefies, then transfer the oxtails to a large bowl. Bring the broth back to a simmer. Add the roasted vegetables and continue to simmer, uncovered, until just knife-tender, about 15 minutes. Return the oxtails to the broth and simmer until they are warmed through, about 5 minutes more. Taste the broth and season with salt.

Serve the soup hot, garnished with the dressed watercress.

Reprinted with permission from Mister Jiu’s In Chinatown: Recipes and Stories from the Birthplace of Chinese American Food_ by Mr Brandon Jew and Ms Tienlon Ho, copyright © 2021. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House._

Mister Jiu’s in Chinatown: Recipes and Stories from the Birthplace of Chinese American Food by Mr Brandon Jew and Ms Tienlon Ho