THE JOURNAL

Paris Galibier, 2008. Photograph courtesy of Condor Cycles

As the late New York Times contributor and science writer Mr Daniel Behrman once wryly observed, “the bicycle is a vehicle for revolution”. No mode of transport is perhaps as egalitarian and capable of moving the masses as the bike (plus, you know, the wheels go round). Sure, a pair of shoes by themselves will work, but they will only get you so far, and while in this day and age you can easily drop the same amount of money on a carbon-fibre road bike as you would on a secondhand car, the humbler models remain one of the cheapest – not to mention healthiest and most practical – ways of getting from A to B.

Being a cyclist also frames your world view. Something well known to former Talking Heads frontman Mr David Byrne, who noted in his book Bicycle Diaries: “On a bike, being just slightly above pedestrian and car eye level, one gets a perfect view of the goings-on in one’s own town.” After all, you’re travelling at a speed that is faster than walking, so you cover more ground, but not so fast that you aren’t able to take in your surroundings, as is often the case in a car.

It makes sense that the bicycles we choose to ride can also shape the way we think about cycling itself, and even whether we consider the activity as a means of travel or as a sport. Whether you ride a road bike, mountain bike, BMX or a fixie, they all share common ancestry – the earliest examples of what we would recognise as the modern bicycle, which first appeared in the late 19th century. (These bikes also provided the blueprint, as well as the road network, for the car, and motoring industrialists such as Messrs Karl Benz and Henry Ford were keen cyclists.)

Here, then, are eight bikes that have set in motion great social shifts and changed the way we think – and ride.

The original

Rover Safety Bicycle, 1885. Photograph by SSPL/Getty Images

The world would be a very different place without the Rover Safety Bicycle. In fact, the world would be a very different place had someone acted on the sketch of a chain-driven bicycle that first appeared in Mr Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus way back at the tail end of the 15th century. As it was, it took close to 400 years for us to catch up, when British inventor Mr John Kemp Starley created the Rover Safety Bicycle, among the first production models to incorporate a working chain mechanism. It featured a large sprocket on the pedal cranks connected to a smaller sprocket on the rear wheel, which multiplied the ratio of pedal turns to wheel revolutions. In other words, you could build a bicycle with two similarly sized wheels rather than rely on one oversized one, which explains why you don’t see many people teetering around on penny-farthings in 2017. This innovation helped make the bicycle the accessible vehicle it is today. Every two-wheeler you’ve ever ridden has its origins in this model.

The road bike

Paris Galibier, 2008. Photograph courtesy of Condor Cycles

Named after a hidden mountain pass in the French Alps, but made in Stoke Newington, north London (confusingly for a company called Paris), this was British frame builder Mr Harry Rensch’s bid to outmuscle the bicycles that dominated the competitions of mainland Europe, notably the Tour de France and the Giro d’Italia. Its unique frame configuration – a pair of narrow parallel top tubes combined with larger down tubes and an offset seat tube – was designed to eliminate “frame whip” (bending caused by excessive force) when ascending or sprinting, dampen shocks and improve handling at speed, but it did an equally good job of turning heads. As with many mid-century design icons – although usually furniture rather than bikes – you can today buy an official replica of the Galibier, hand-built under licence in Italy by London-based Condor Cycles.

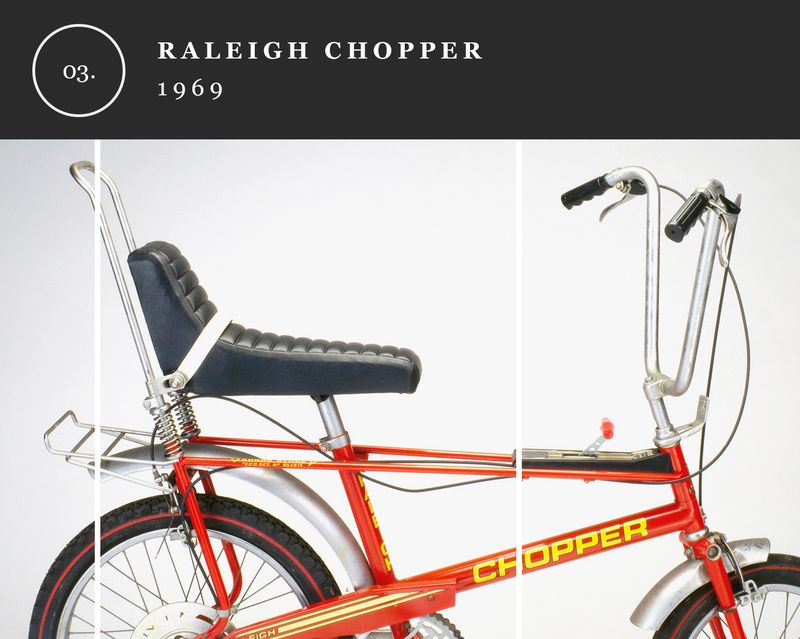

The child’s bike

Raleigh Chopper Mk2, 1978. Photograph by SSPL/Getty Images

If you have any memories of crushing your testicles as a child, it’s probably down to this bike. Inspired by the similarly named motorcycles popularised by films such as Easy Rider (1969), the Chopper is the bike that single-handedly saved ailing British bike house Raleigh, shifting 1.5 million models in the UK alone. Rather than a scaled-down version of an adult’s bike, it was designed specifically for the youth market and became symbolic of teenage culture for anyone growing up in the 1970s and early 1980s, paving the way for the BMX, which eventually signalled the end of the Chopper in 1982. The bike wasn’t without its issues. The distinctive elongated saddle and backrest led to a moral panic over riders giving other children “backies”, while the back-shifted centre of gravity made its handling tricky. Combined with the gear lever mounted on the frame at groin level, it resulted in some painful accidents. A revived version launched in 2004 ironed out many of these quirks, which purists might argue gave the original its character.

The tourer

Dawes Galaxy, 2013. Photograph courtesy of Dawes Cycles

By the 1970s, touring on a bicycle had become both a popular competitive sport and leisure activity. People wanted to go further on their bikes, often over days if not weeks or even months. A machine up to the task had to be strong but reliable and easy to maintain on the road with only a few tools. It also had to carry a heavy load (ie, everything you’d need for the duration of your trip), but must be comfortable (you’re going to be in that saddle for some time). Before the Galaxy, most touring bikes were custom-built specialist models, and therefore prohibitively expensive. This mass-produced, off-the-peg bike made touring accessible for the more casual cyclist. So much so that the bike is still in production today.

The mountain bike

Specialized Stumpjumper, 1981. Photograph courtesy of Specialized

A decade on from the Galaxy, the Stumpjumper had a similar impact on the emerging mountain biking sector, opening up what had been a niche pursuit to the wider world. In its infancy, the sport had been the preserve of a few specialist frame builders. By the end of the 1980s, sales of mountain bikes had overtaken those of road bikes, thanks in no small part to this model. Based on a design by Mr Tom Ritchey, one of the pioneers of the new frame geometry, but less than half the price of an equivalent hand-built bike, the first batch of Stumpjumpers sold out within weeks. There proved to be no rapid descent on the other side of this peak, either. The bike helped to ensure that what began as a craze grew to become a whole new branch of fitness.

The BMX

Kuwahara KE-01 ET 30th anniversary limited edition, 2012. Photograph courtesy of Kuwahara

As unlikely as it sounds, Sir Chris Hoy owes his cycling career – and six Olympic gold medals – to ET: The Extra-Terrestrial. The BMX bikes that famously feature in Mr Steven Spielberg’s 1982 film (and spurred a generation of children, Sir Chris among them, to take up two wheels) rose out of the motorbike-inspired dirt-track racing of 1970s California. The first bikes used for this fledgling sport were often customised Raleigh Choppers or Schwinn Stingrays, but as bicycle motocross (hence BMX) grew, purpose-built bikes followed and new disciplines, such as freestyle or stunt riding, emerged. Freestyling soon spread to skate parks, with riders such as Mr Bob Haro becoming its stars and figureheads. As well as having his own line of bikes, Mr Haro even performed stunts in ET. The film catapulted the sport – and the bike – further. The featured model, a limited-edition Kuwahara KE-01 (above), was released to mark the movie’s 30th anniversary.

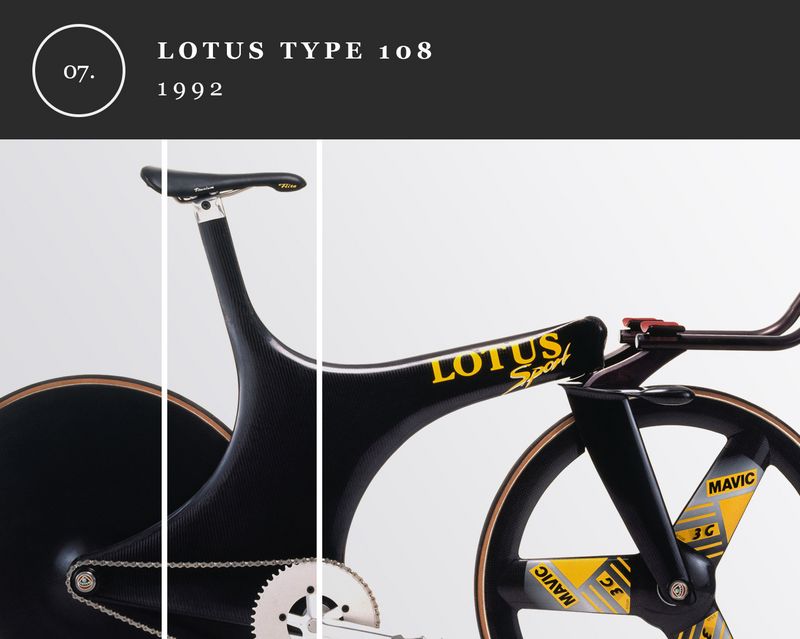

The track bike

Lotus Type 108, 1992. Photograph by SSPL/Getty Images

Individual pursuit is a cycling event that pitches two riders against each other. Starting from stationary positions on opposite sides of an oval track, there are two ways to win: either post the fastest time or overtake your opponent. The latter option exists almost as an unobtainable goal and remains largely unheard of in the sport, but that is exactly what Mr Chris Boardman did in the 1992 Olympics final in Barcelona to win the gold medal. The carbon-fibre monocoque “superbike” he rode, the Lotus Type 108, was developed by employing the same wind tunnels used to craft the firm’s sports cars. It opened up an arms race in bike design, which ultimately led cycling authorities to impose restrictions on what was termed “technical doping”, and has had a lasting influence on aerodynamics in general, beyond the velodrome.

The fixie

Bianchi Pista, 2007. Photograph courtesy of Bianchi

Whisper it, but the fixed-gear mechanism is something of an archaism. Despite (or perhaps because of) being supplanted by the invention of the free-wheel hub, which allows the pedals to remain stationary while a bike is in motion, the “fixie” was embraced by track cyclists and later urban couriers, and has since enjoyed a modern-day resurgence. It has become the bike of choice for purists, who suggest it provides a more involved riding experience. Not that there isn’t room for improvement – within reason, of course. Here, Bianchi has polished its perennial Pista model. The 133-year-old Italian marque is perhaps better known for its bluish-minty green colourway (“celeste”), which, legend has it, harks back to a bespoke bike built to match the hue of an Italian queen’s eyes (thought to be Queen Margherita of Savoy, who also gave her name to the pizza), but this shiny bare chromoly finish works with the stripped-down aesthetic favoured by fixie riders.

Adapted from Design Museum: Fifty Bicycles That Changed The World (Conran Octopus) by Mr Alex Newson