THE JOURNAL

When Mr Trent Preszler told his mother he was planning to use his father’s old tool set – his sole inheritance – to build something out of wood, she assumed the “something” would be simple and basic. Such as a chopping board. Preszler, the CEO of a small winery on the North Fork of Long Island, New York, had never used his hands to make anything. He could explain in detail the character of his vineyard’s 2009 merlot, served at President Barack Obama’s inaugural luncheon, but ask him to hand you a Phillips screwdriver and he’d be stumped. Is that the one with the star-shaped end or the flat edge? Frankly, a chopping board seemed a stretch.

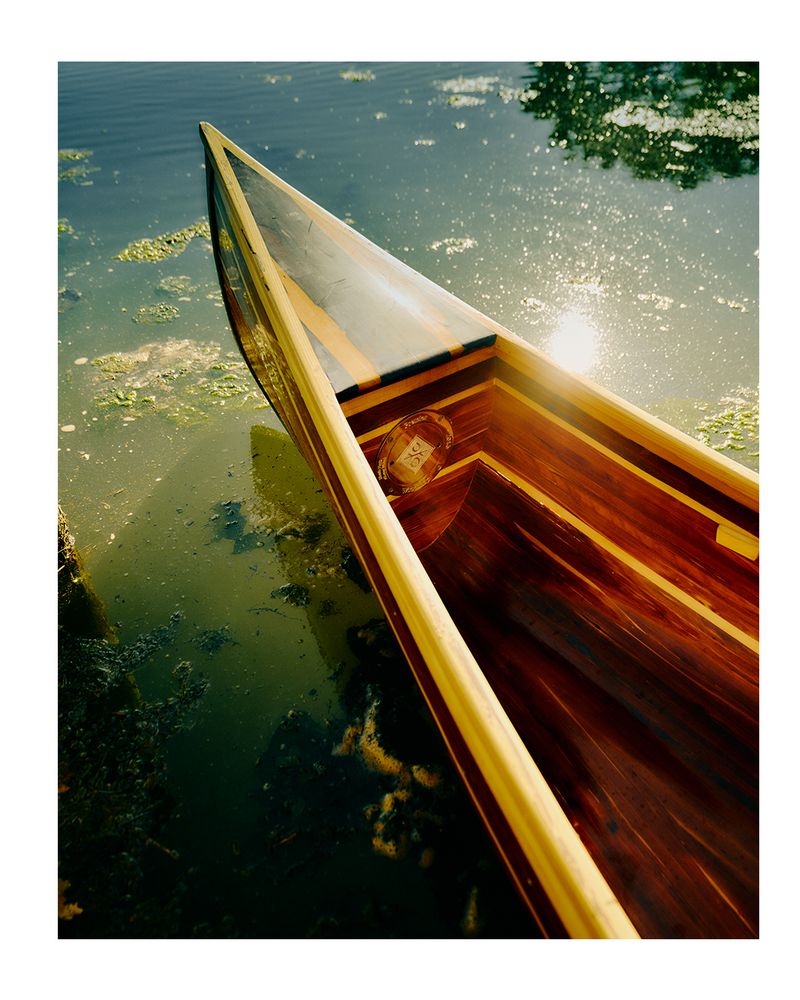

So you might forgive his mother her scepticism when her son told her he was planning something quite a lot bigger and vastly more complicated. Despite having zero boat-building experience, Preszler was going to make a 20ft-long canoe of cedar, walnut and ash and sail it on the first anniversary of his father’s death.

No ordinary canoe, either. It would be fully tricked out, applying the principles of superyacht luxury to what historically was purely utilitarian. There would be woven hemp and saddle-leather seats. There would be a crystal and bronze bezel yacht compass. “For hundreds of years, people have assumed that a canoe has to be lightweight and ugly,” says Preszler. “I thought, I’m going to make it absolutely fabulous.”

Preszler had grown up knowing that his father could build anything. Now he wanted – needed – to prove that he could, too. The tool box was not just an inheritance; it was a challenge. For 14 years, the two men had barely spoken, but his father’s death had undone years of pent-up anger and bitterness. Building a boat felt like a way to get closer to a man he’d never fully understood.

Preszler has a seminal memory of sitting in an aluminium canoe with his dad on their last duck-hunting expedition together, carrying Winchester 12 gauges over their shoulders. “Hunting was the way we spent time, even if we didn’t say a word to each other,” he says. “We’d sit in a duck blind for five hours in the shivering cold, waiting for a duck to fly by, in complete silence. And it was the closest I ever felt to him.”

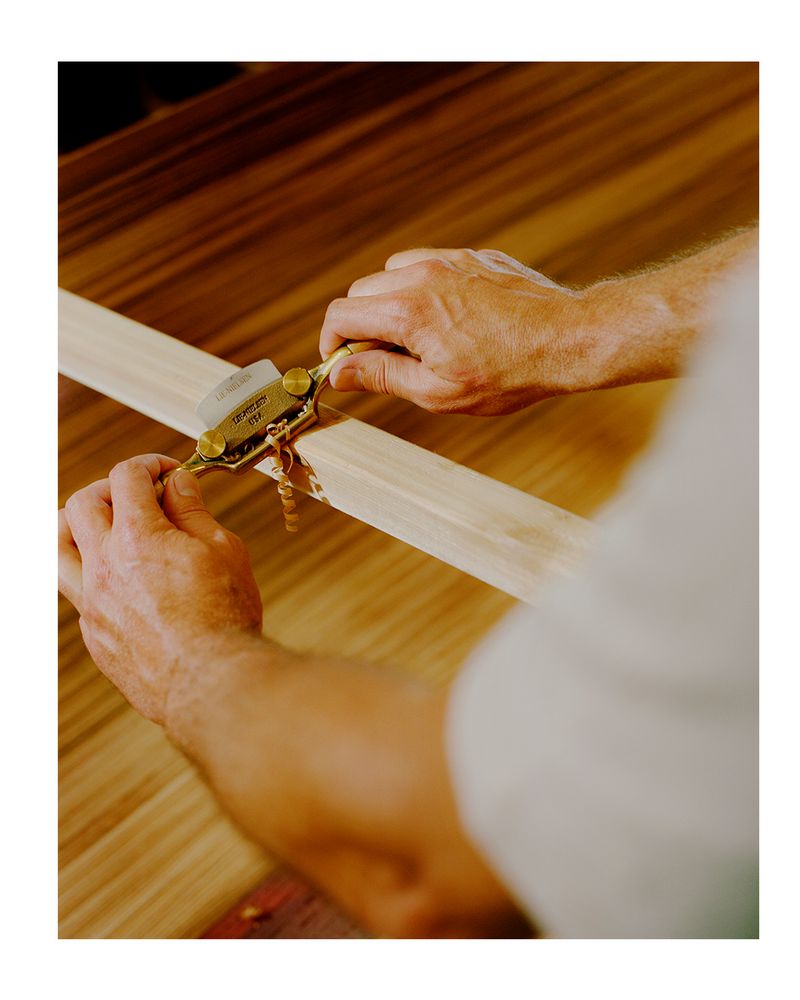

It wasn’t only Preszler’s mum who doubted his ambition. A colleague at the winery suggested that, instead of a boat, he try his hand at macramé. Preszler was undeterred. Using his father’s tools for the first time was a revelation. They fitted his hand as if they’d been made for him. Feeling the weight and shape of them, Preszler was assailed by an unshakeable conviction that he would build his way out of his emotional crisis.

As part of his epiphany, he went full Marie Kondo on his beachfront home, a way to exorcise the complicated feelings left in the wake of his father’s death. He wanted a clean slate. Little survived the purge, not even the beds. Instead, he kipped in a sleeping bag, stored his clothes in two suitcases. “Throwing everything out was an external reflection of what was going on inside,” he says. “Here I was, 37 and, to the casual observer, I was successful, a CEO of a winery, the guy with a PhD and my act together, but I was just torn up on the inside.”

Preszler retained one thing of sentimental value: the duck he’d shot on that final hunting expedition with his father. At some point it had been stuffed and mounted – the only time his dad had done this. In the choked emotional language of fathers and sons, it was as close to saying, “I love you,” as either man had ever come. Preszler carried it back with him from South Dakota along with the tool box.

That Preszler made his boat, and on time, turns out to be almost secondary to the much richer story of false starts, wrong turns and existential crises that he recounts in his elegant memoir, Little And Often, in which he alternates the trial-and-error story of building a canoe with flashbacks to his hard-scrabble childhood on the prairies of South Dakota.

What emerges is an ode to perseverance and to the redemptive power of using your hands, the elemental thrill of mastering a skill. It’s also about his effort to make sense of his father, an evangelical Lutheran, Vietnam veteran, cattle rancher and rodeo champion, and a poster boy for a rugged cowboy masculinity that Preszler, who is gay, could never emulate.

As a child, every mishap and accident seemed only to amplify the gulf between them. An incident with a rampaging bull during which a fleeing Preszler smashed his hand in the door jamb of a trailer, is illuminating. “In between screaming obscenities at the bull, my father said something else to me: ‘You ain’t never gonna be man enough.’” It was a jibe that haunted him.

Today, he understands that what was absent in his childhood was the routine validation that young straight men take for granted. But he’s also found that his experience is more universal than he first thought. “I have gotten hundreds of notes from people who’ve read the book, straight white men, mostly, who start reading it thinking it’s a woodworking book,” says Preszler. “It’s like the Trojan Horse. They’re halfway in and they realise this is not a woodworking book.” He laughs and then sighs. “America has a lot of daddy issues. All these stoic, unresponsive men.”

If you ever plan to visit the North Fork of Long Island, don’t take, as Preszler did the first time he visited in 2002, local State Route 25, with its endless traffic lights. You will crawl. You may, in fact, crawl even if you take the woefully misnamed Long Island Expressway, as I find myself doing 19 years after Preszler’s maiden trip, cursing the entire way. But then you exit into a jigsaw of farms and colonial towns and feel transported. There is the tang of salt in the air, the flash of ocean, the endless stands with their chalkboards promoting freshly picked asparagus, sweet peas, spinach and lettuce. I arrive on the eve of an annual strawberry festival.

“I can take the canoe out and just glide into these little inlets and sit there and listen and watch”

When Preszler came here in 2002, he thought the Hamptons (aka the South Fork) was a mountain range in Massachusetts. He’d just graduated from Cornell University and had been hired by Mr Michael Lynne, a movie mogul turned winemaker, who liked Preszler’s 300-page Master’s thesis analysing the market for New York wines. “I met him in his office in Central Park South and he said, ‘I have to hire you because no one else will,’” says Preszler. “He said, ‘I read your thesis and it’s so nerdy, and I don’t think anyone else in the local wine industry will appreciate it.’” So, Preszler stayed, thinking he’d be there for a year or two, maybe a little more. Now he thinks he may never leave.

The canoe has cemented his relationship with the area and given him access to a hundred creeks and inlets that sawtooth the peninsula. It has, in a sense, anchored him. He describes sitting in his canoe, watching an osprey swooping down to grab a fish from the ocean, the kind of theatre he never tires of. “I can take the canoe out and just glide into these little inlets and sit there and listen and watch,” he says.

We are standing in the garden of Preszler’s new home, a spacious 1970s bungalow on a high bluff at the edge of the ocean. He points across Long Island Sound to the horizon, unusually crisp and clear on this warm June afternoon. He traces the outline of a depression along the distant shore, across the whitecaps that separate us from Connecticut.

“That’s the channel of the glacier that came down from New England and created the North Fork and the Hamptons,” he says. “This whole strip of land is made of piles of gravel and rock that the glacier pushed in front of it.”

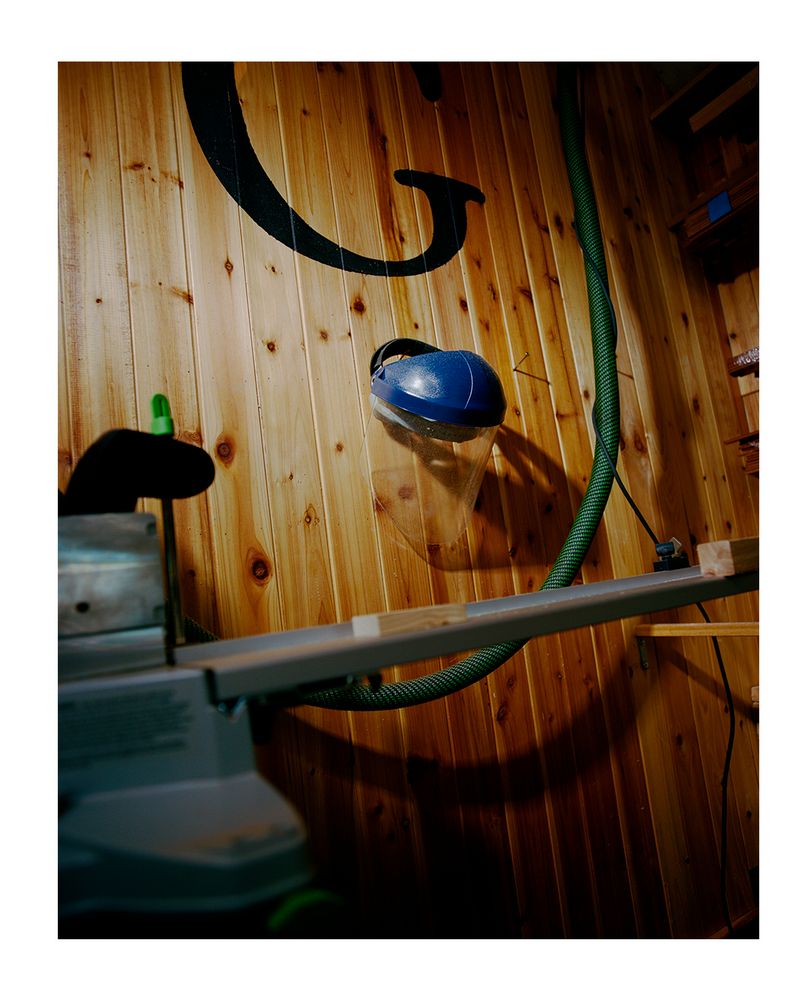

That was 11,000 years ago, which predates the world’s oldest-known canoe only by about 700 years. We’ve been navigating the oceans ever since, though rarely in vessels as breathtakingly beautiful as Preszler’s. He has made several more canoes, which he’s sold for $100,000 (£74,000) a pop, since his maiden voyage. A new order for a country singer will soon take shape in his immaculate workshop in nearby Mattituck.

It sounds like a lot of dough until you account for the cost of materials (Preszler estimates $20,000 to $30,000 even without the crystal and bronze bezel yacht compass) and labour. Then there are taxes. “There’s a chronic problem in the American craft world of people who underprice their work because everything is a race to the bottom with Ikea and Amazon,” says Preszler. “People want everything cheaper and faster and they don’t realise that well-made things cost money and take time, and that if you want those things in your life and you value and cherish them, you have to consciously make space for them.”

He is an acolyte of Mr EF Schumacher’s landmark 1970s book Small Is Beautiful, in which the economist makes the case for smaller, more humane and ethical economies. “When I hear some MBA use the word scaleable, just shoot me,” he says. “I’ve had these hot-shot Wall Street bros who make millions of dollars approach me, like, ‘Hey, bro, what if I get some VC for you? What if we blow this out, bro, and you make, like, a hundred a year? We can just scale the whole thing.’”

A burst of bird song cracks the early-evening silence. “Do you hear that?” says Preszler. It’s an eastern mockingbird.”

We make our way down through a glen of beach trees to the white sandy beach below, while Preszler’s rescue dogs, Isaac and Rose, run in looping circles around us. Hurricane Sandy did a number on the dunes here in 2012. Now Preszler is working to restore order, planting 100 native pines to prevent future erosion.

“Probably half are going to die,” he says and shrugs. Failure, he knows, is one half of success. A moment later, he spots a small oak sapling pushing through the sand and is filled with elation.

Standing on that white sandy beach, it’s easy to forget that Preszler spent his youth on the prairieland of South Dakota, where cows outnumber humans by five to one and the ocean is about as far away as is possible in the US. Even the nearest McDonald’s was 150 miles away from his hometown of Faith (population 421). At his one-room school, he was the only pupil in his grade and received just an hour of in-class tuition a day to allow the teacher time with the seven other grades. Self-directed learning before it was commonplace.

“When I go back to South Dakota, I feel like a tourist in a strange land now,” he says. But still he is steeped in sense memories of childhood – the feel of the leather saddle the first time he went riding with his father, the rustle of sharp-tailed grouse taking flight as they trotted through cottonwood trees, the stillness of a morning duck hunting on a lake.

Back in the bungalow, Preszler retrieves a canvas L.L.Bean bag and pulls out the few totems of his childhood that he saved: the spurs he was given at the age of nine; the hip flask his father took to Vietnam, complete with two intact shot glasses in their own tiny compartment; the belt-buckle trophy awarded to his father in 1968 after winning the rodeo championship. Although he spent a long time running from his childhood, building the canoe and writing his memoir have cauterised the old feelings of resentment.

“It was all an interrogation of my memory, to weave a thread, to make sense of it all,” he says. “Until you write that stuff down, it doesn’t really sink in I think.”

Early in Little And Often, Preszler recalls how his father’s tool box went with him wherever work had to be done. “I began to think of the tools as keepers of family stories that only I could unravel,” he writes. Now the tool box sits in his restored workshop on the North Fork, just below the stuffed duck. The tools are not finished yet. They have work to do and new stories to tell.